As its name suggests — and rightfully does so — the exhibition The Missing Thread: Untold Stories of Black British Fashion pays tribute to the incredibly influential work of Black creators, which has often gone without acknowledgment. In doing so, the exhibition points to the underlying structural racism that keeps Black designers and artists from entering the industry — or from gaining recognition.

Curated by the visionary minds behind the creative agency BOLD (Black Orientated Legacy Development Agency), Jason Jules, Andrew Ibi and Harris Elliot went beyond putting together a fashion exhibition, or an exhibition about history, by placing Black fashion within broader socio-political and cultural contexts. In that sense, the exhibition digs into different themes and sources of inspiration that have informed the course of fashion since the 1970s.

TITLE had the opportunity to sit with writer and creative director Jason Jules, known for his various specialties in the fashion industry, and discussed how the exhibition at central London’s Somerset recognises the contributions of Black designers whilst challenging preconceived notions about Black culture and the way black exhibitions are meant to be.

Hi Jason, how do you feel about the recently opened exhibition The Missing Thread?

I’m super excited about the exhibition, because it’s taken about 3 or 4 years to bring to fruition, and in a way, as we kind of initially conceived it all those years ago. It’s really gratifying to come up with an idea to enrol tons and tons of people. The production was enormous, and then to actually see it come to life, but also to see the responses from loads of people — they’re getting it, even though it’s quite an experimental exhibition.

That’s very exciting. Why do you say the exhibition is kind of experimental?

We kind of gave ourselves the remit of looking back at the past, say, 40 years of Black British fashion. And ordinarily, you’d imagine that you’d do it in chronological order. It started in the ’70s and ’80s, but we decided to do it in a kind of a thematic way — in a way that was way more emotional and contextual than historical. One reason being that, there isn’t much historical documentation about that period at all. And if there is historical documentation, then it’s kind of biased or pretty much negates the contribution of Black people.

So we had to kind of construct our own timeline and our own way of seeing the world, because it didn’t exist before. You know what I mean? So rather than try and do something that was following a historical pathway, we figured we’d actually do it in terms of themes, and the themes would be a lot more empathetic and empathic as opposed to kind of factual. So people who would attend the exhibition would actually come away with a feeling as well as an awareness. That was the goal. And I think that’s why it’s experimental, because ordinarily, it’s kind of like a fashion history.

What are those themes?

There are five themes and there are contextual themes or challenging things within those. The first overarching theme is home. So the idea is that as immigrants, our parents and grandparents arrived to the UK from the West Indies or West Africa, based on being invited. And this is actually their home, because, for example, my mother came from Saint Lucia, which was a British colony — so she was British. She was actually going home when she went to the UK. At least that’s what she was told. So we’re exploring the idea of what home means to an immigrant. you go to ‘home’ and the first thing you see is this timeline — this wall of newspaper cuttings. And essentially it’s covering a fireplace. So it actually looks like the wallpaper is now the newspaper and you’re actually in a home, but it’s kind of invalidated by current affairs. And the current affairs are kind of interrupting your peace, your sanctuary.

In terms of the Englishman’s home, home is his castle. This is what we’re told. And so ordinarily you would see in terms of West Indian replicas very colourful West Indian homes. There’s lots of kind of doilies and pictures of family and all this stuff, and we decided to strip away all of that and basically do a kind of a deconstructed version of it. So people who have experienced those homes will actually really understand what’s going on — that for most West Indian families in the 60s and 70s home was a sanctuary.

But it’s also a place of contention. And, you know, most of them being working class was a place of stress, you know, pay the mortgage, pay the rent and taking the home, looking after your kids. All those tensions are parcel of that experience. But also the tensions of racism and the idea of not really being at home or comfortable in that space.

After setting a premise based on this experience that is not a choice or a fantasy response, we explore how the idea about fashion coming into is important. This initial kind of ambivalence with home leads to the next space that is called tailoring. It’s about people who have come to the UK and are looking to become part and parcel of the culture. If you’re in fashion and you come to Britain, then the home of British fashion is tailor. And you know that you’re really going to do the holy grail of tailoring if you go to the UK.

A lot of West Indian people came from having studied tailoring and seamstress work in the West Indies and saw that as a profession for life. They get to the UK and they want to practice that craft, but they can’t because there’s a closed shop. So they have to find different ways of doing that. And that would happen in all sorts of industries, from driving buses and trains to all sorts of stuff in the UK into the 70s as well.

You go into tailoring, you try and do it by the book and you fail. There’s a resistance to you being accepted. So in order to overcome that resistance, you try and prove your value. You try and prove your Britishness: I am as British as the next person. This is all I know, and I’m going to prove that I’m a contributing citizen. So that’s what the performance space is about. It’s about musicians, artists, sportspeople, and more. But there’s an ambivalence about it because you’re welcome, but you’re always conditional if you’re not in it.

Then the next space is nightlife, which is, in a sense like the final space, but not really. Nightlife is — as I’m sure you know, especially in Berlin — not just the place. It’s like a mindset. So it’s almost like you’re going into this particular space and it’s on your own terms, because the standard rules of normal everyday life don’t really apply. So you’re stepping away from convention and you’re moving into living on your own terms. So this is what we’ve called nightlife, which is where kind of secondary industries will be developed. So there’ll be a guy who has a clothing shop. He also has a barber shop. There’ll be a nail bar. There’ll be fashion designers, dancers, musicians, all sorts of entrepreneurial stuff. But those kind of aspirations aren’t based on the mainstream expectations. They’re based on this other kind of subterranean ideology, which doesn’t need the approval of the mainstream. In fact, it’s often either ignored by the mainstream or frowned on.

And that’s the next stage, it’s a kind of self-idealisation: it’s me seeing myself on my own terms as opposed to the previous ones, which was me seeing myself defined by the mainstream. And then the Last Space is dedicated to Casely-Hayford, who is, to my thinking, the best designer the UK has ever had. And he was a Black designer, but he resisted the idea of being defined as a Black designer only. However, he basically absorbed all those things that we show in the previous zones and expressed them through his work. So the last space holds 30 or 40 pieces from his archive.

Is the exhibition’s curation evocative or rather literal?

It’s definitely evocative, but it’s paced. You walk in and the first thing you see is this beautiful, kind of three dimensional wooden assemblage against the wall, which is so colourful that it’s ridiculous, almost tasteless. It’s called the Banana Boat, and it’s done by a guy called Robbie Waters, who is a London based artist. That is a metaphor for our journey to the UK. It’s about the whole history of how we became colonised, but also it’s about the colourfulness of what we’re leaving. You’re entering into the UK, and the first set of images are black and white. So that’s kind of like the, the series of metaphors that go on.

Would you say this is a fashion exhibition?

Yes. It’s both a fashion exhibition and in a sense, an empty fashion exhibition. In a way, that is if we think of fashion as something that is trend based and disposable and focused on consumption. This is the opposite of that. This is about how people use clothing to create identity and to communicate with each other, and to get a sense of themselves and to find a sense of belonging.

What do you think is the story that The Missing Thread tells about fashion and in general about pop culture?

I think it tells a lot of stories, and because there are three of us constructing this thing, I think we might all have our own take on it. To me, one of the things that it hopefully demonstrates is that if you’ve got a preconception about what Black culture is, then this will challenge you. In the spaces you’ll see some fine art by someone like Chris Ofili, who was the first black Turner Prize winner in the early 90s, and the dress worn by Princess Diana designed by teacher Bruce Oldfield. And so it kind of counters the assumption that Black fashion is streetwear or that’s purely sportswear.

Do you think the exhibition offers solutions or look for reparations anyhow?

I think, in a weird way, the goal for me is to offer at least one solution and that would be to say to my younger self, when I was 16 and was thinking about what I would do for a living and I didn’t know of examples of designers or people from my background in the fashion industry. And whenever I spoke to people, you know, career advisers, parents, teachers, they’d say, forget it.

I think this exhibition hopefully will demonstrate to 16 year-olds who are thinking about being in fashion that actually there is a possibility for them. And also that is not prescriptive just because you’re into fashion and you want to design as a Black creative doesn’t mean to say you have follow a certain path. But beyond that, I don’t think there are. I don’t think we’re trying to offer solutions. I think we’re trying to basically celebrate diversity and creativity. If you come away with a sense of possibility from having seen this show, then that’s the entire job.

I love nail bars 100%, so the nail bar caught my attention. And I wanted to ask you, what can this night section tell us about beauty trends in pop culture today, or how are they influencing today’s culture?

Yeah, I guess that’s the other side that we didn’t really want to focus on, but it’s obviously evident. The fact is that a lot of what happens in terms of underground culture and Black culture is seen and appropriated by the mainstream and often colonised and separated from its original roots.

You can see that you can get a sense of the source of a lot of the trends and the ideas that are quite prevalent now from walking through that nail. But to me, it was a conversation about Black design and style and culture that was being had between Black people. And for a mainstream audience to come in and see it in the most authentic sense. So we’re not trying to address anything to appease or to interest the mainstream.

How did you make the exhibition happen?

Well, to be honest, the actual show took us a year to put together because we’ve been discussing it for a number of years, and we had planned to do with the British Fashion Council, and somehow that project didn’t come to fruition. So we kind of parked it for a while. And then maybe a year and a half ago, Jonathan Rudnick from Somerset House contacted Harris and said, you know that show we discussed a while ago, are you doing anything with?

Somerset House found us a sponsor and we had a year to do it. So we pulled on all our friends and contacts and the community and the wider community and it worked out.

The idea for the exhibition came from BOLD, the agency that you, Andrew Ibi and Harris Elliot founded a couple of years ago. How did you come up with the idea of BOLD?

We decided that even though we are free, very individual, very strong willed creatives, if we combined our identity, in a sense, as a singular voice, that would make us stronger and give us a unified tone, but also make it more difficult for people to separate us and weaken our mission. So the idea of BOLD was to be a kind of collective so there can be more people coming in as well as people moving out. But generally, to be unified. And when it comes down to, for example, who the conversation about who did what or who’s better at what, I think those conversations are kind of almost a secondary or irrelevant to to the end result, if you know what I mean. A lot of the time, especially for Black creators, there’s this idea of separating them from the kind of cultural context, and we were trying to kind of mitigate the possibility of that by setting up this agency called BOLD.

So this is a platform for creatives?

Yes.

I imagine one of the ways that you’ve materialised your mission is through the exhibition. What are other venues for that?

There’s another extended project, which is basically the Joe Casely-Hayford archive, ongoing project. One of the first things we did before the exhibition, was an article almost like a testimonial to an idea magazine. And we launched that with a talk on Show Studios as well. The article has about 30 to 40 people basically saying what they saw in him and what they remembered.

We’re setting up a digital library, which we eventually will become something a lot bigger. The digital library is dedicated to his work, but also to the work of Black creators as well, in terms of fashion and design. Another thing that Andrew has done is set up a company about Black academics in fashion and that’s about empowering and giving them a sense of support as well as a sense of presence.

And again, one of the things that this exhibition for me was important was not just because of doing the actual thing, but also because of the stuff around it, like the conversations and the documentaries — all those pieces will outlive the exhibition. They’re almost as important, if not more important than the show itself. There’s no way that we’d be able to do this alone. And I think that’s one reason why we had to rim fence ourselves as a group so it becomes separate to us and leaves on its own.

One last question. A lot of what is surrounding Black culture these days is being tokenised and I wonder, how do you keep the balance between being authentic and avoiding tokenising culture in general?

I think you remain authentic to yourself by asking and asking yourself those questions. And also, how it makes the people around you feel uncomfortable. If everyone is super comfortable with what’s going on, maybe you’re not doing the right thing because the landscape is completely imbalanced in terms of perspective and priorities. And so oftentimes if you’re being authentic, then you’re actually challenging the landscape and you’re going against the conventional point of view.

One of the things that was inherent in this project is that it was very challenging. We were challenging a lot of people’s ideas about what Black-star was meant to be, and we were challenging a lot of people’s ideas about what a black exhibition was meant to be, but also the idea of what beauty is and what violence is.

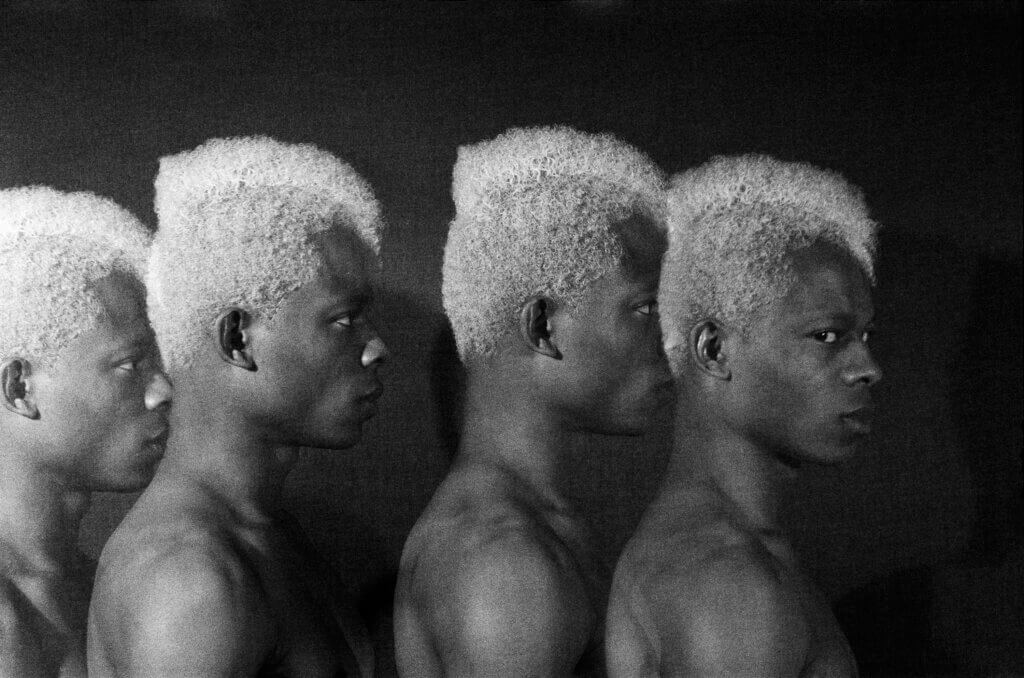

*Header: Bianca Saunders ‘YELLOW’ SS20 campaign. Shot and Styled by Ronan McKenzie

All images courtesy of Somerset