The Enigma of Murakami’s Female Characters: A Dive into Representation and Narrative Patterns

Those who have read a book or two by Haruki Murakami might have noticed, among the surrealism and the cinematic descriptions, a narrative pattern that repeats over his characters. Men summon up their own worlds and embark on lonely, retrospective journeys. They are compelling, unpredictable and enigmatic. Certainly, captivating and intuitive. However, Murakami’s creative energy to depict women falls short: they often emerge as the sexual accomplice of the male characters. The reinforcement of outdated gender roles in Murakami’s novels has been much discussed in recent years, in a time that is rife with questions about female representation — and the depiction of female bodies — in literature. This question was initially and lightly touched upon in a previous article discussing Murakami’s adaptation to the cinema.

Murakami’s mesmerising narratives are repeatedly composed by a solitary male lead, an ephemeral yet intensely sensual female presence, and a surreal odyssey that blurs the boundaries between the ethereal realm and actual reality. The encounter of the sexualised female energy marks a moment of transcendence, as if women were a catalyser of spiritual journeys and their bodies the chaperone to these fantastical worlds. In other words, women are “vessels of liberation for male characters,” as many have referred to Murakami’s female characters.

But it is not only the role of women as sexual objects that poses an issue of representation for many. Murakami’s storytelling invites us to look into these fantastic worlds from the eyes of a cis-man, a narrator who experiences the world through the male gaze, entitled to fantasise about the intimate lives of women. For instance, in Killing Commendatore, an unnamed 36-year-old portrait artist meets Mariye, a 13-year-old girl whose first words are, “‘My breasts are really small, don’t you think?’… I can’t help thinking about my breasts,’ Mariye said after a while. ‘That’s all I think about, pretty much. Is that weird?’” But how can a pre-teen share these concerns so openly with a much older man — a man she doesn’t even know?

In a recent conversation between Murakami and Mieko Kawakami, author of the internationally acclaimed “Breasts and Eggs,” they discuss the relatability of this excerpt. Murakami explains that Mariye’s obsession with her breasts reflects his perception of how girls feel and communicate about these concerns. However, one must question whether women genuinely express themselves in such a manner, amicably and detached from societal prejudice, or if these conversations inadvertently invite sexual objectification. Is Mariye portrayed as unnaturally mature for her age, lacking character and the ability to make sound judgments?

And like that, most of Murakami’s female characters seem to neither add much to the plot nor undergo character development. On the contrary, they are predictable and uninspiring, almost lifeless, becoming relevant only to the role of man’s accomplice. For instance, in many other stories, male narrators have dreams of having sex with women without their consent, as happens in Kafka on the Shore. However, no matter how unreasonably available women make themselves in Murakami’s stories, this pattern of sexualisation offers comfort, escapism and fantasy to many. In fact, in online conversations on this topic, many readers say they find Murakami’s portrayal of women realistic, even convincing. Literature can be revealing, but also a reinforcer of systematic structures

The topic of female representation is gaining more attention with the passage of time, and many authors are aware of avoiding representing bodies as such depictions have become their enemy. No matter the intention, these portrayals convey to one or another extent inaccuracies, offending the audience and sparking backlash. But can avoiding the representation of female bodies solve the problem of the male gaze?

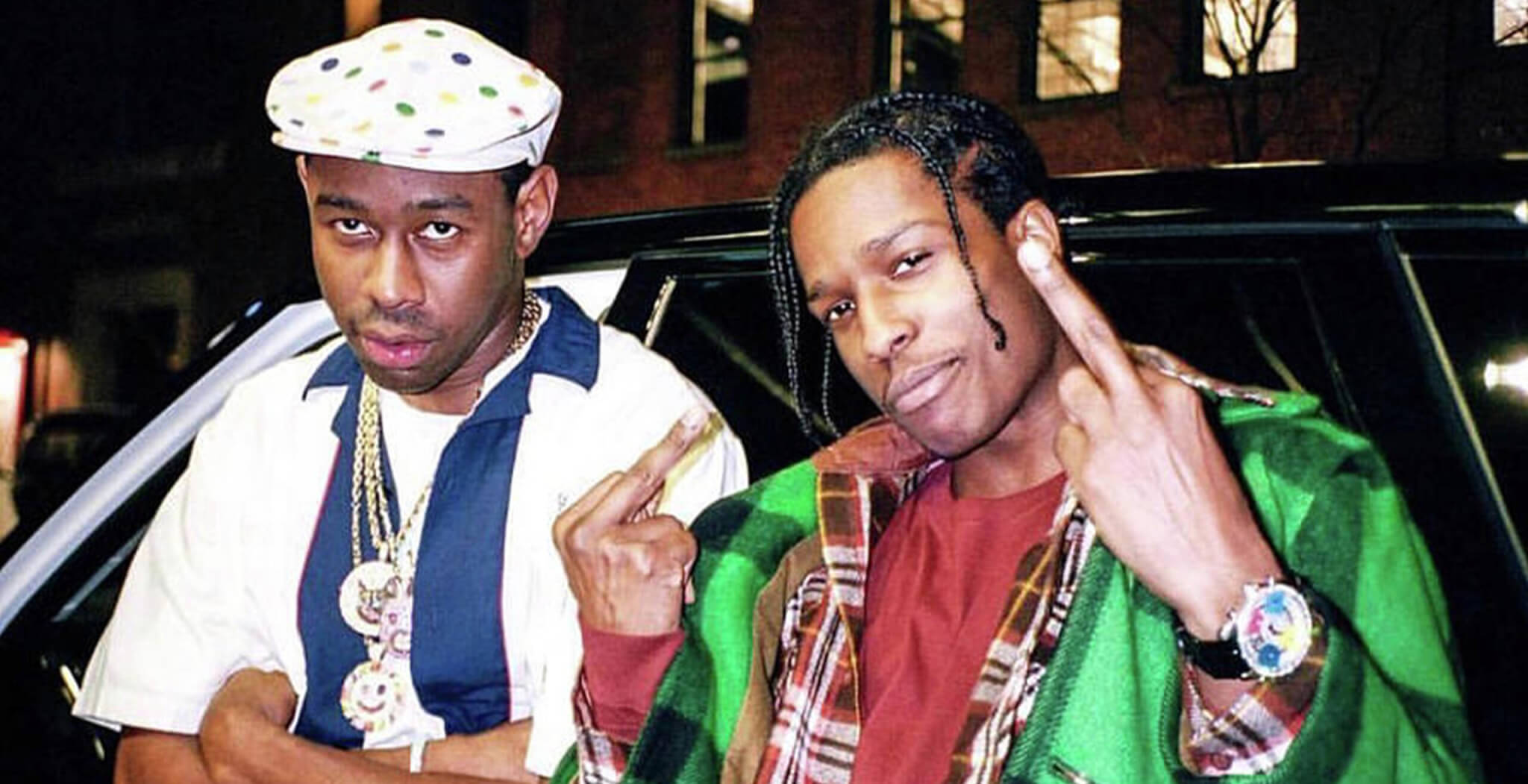

*Header image: Burning, directed by Chang-dong Lee (2018)