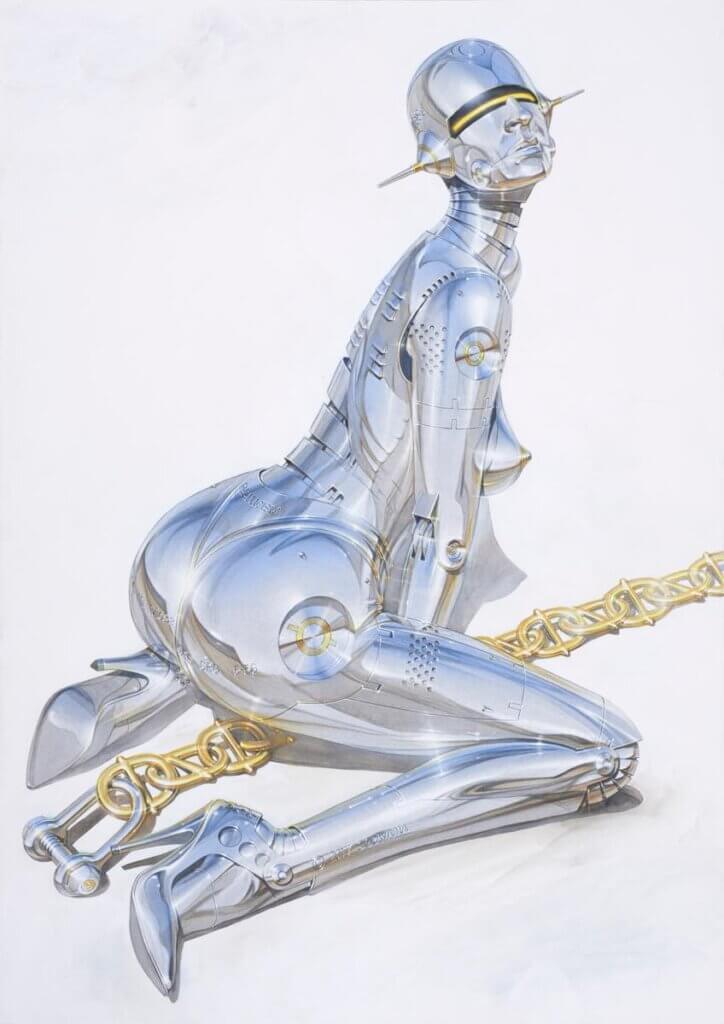

Western pop culture was thriving on fantasies about the future of technology and how it could intercede our societies — both in horrific and pleasurable ways. It was then that Hajime Sorayama turned sci-fi literature and films into drawings that depicted the future of the female human, defined by technology, intertwined with mainstream ideas of the perfect woman.

Sorayama’s chrome-plated paintings, surrealist style and use of the airbrush technique have positioned him as a master of realistic expression. However, it is the exploration of taboos and the erotisation of robots imbued with human qualities — more specifically, feminine — that have made Sorayama a worldwide cult artist. His series of Sexy Robots, an ongoing project that started in 1978 and continues to the present day, raises endless questions around fetishism, genetic manipulation and human life, and addresses more immediate concepts such as female idealisation, objectification and emancipation. And also, patriarchy and sex. Censorship and democracy. Two extreme ends of a pole.

Sorayama’s works are controversial and inspiring to a generation that not only condones but encourages emphasising and sexualising female attributes — only think of Betty Grable and Marilyn Monroe, whose images spurred everywhere like free postcards. His provocative exploration of sensuality and erotism in the digital age has earned him collaborations of all kinds.

The collaboration with Japanese tech company Sony made him famous worldwide. He designed the first AI dog, AIBO, which became available to the public in 1999, a year loaded with utter anxiety about the Y2K, as it was believed that a Millennium Bug would be triggered, leading the masses to madness. That New Years’ eve was historical, and Sorayama knew how to seize the opportunity.

Another remarkable collaboration was the one for Thierry Mugler’s AW95 couture show. The piece Sorayama designed was a bodysuit that revealed the breast, complemented by an armour, becoming the first wearable fembot piece. That was only the beginning. His illustrations have been featured in the capsule collections of different designers and brands, from Dior and Juun.J to Forever 21.

Apart from that, his influence is spotted across different sci-fi formats, including Alex Garland’s film Ex Machina (2015), which plot revolves around the protagonist’s affection towards an eroticised fembot. But Sorayama isn’t the first one to fantasise about the possible post-human female. Blade Runner (1982) and Her (2013) have in common the depiction of fembots capable of seducing the protagonist into fatal situations. Their weapon? Their sexuality.

It is not new to note that the potential of women has been inextricably defined by their sexuality, and Hollywood confirmed this by making public only women who could meet beauty standards. By making them public figures they became sex symbols, ready to be consumed. Their images were boxed and delivered on everyone’s door mat without objection. Between the end of the twentieth century and the late nineties, it was generally assumed, according to historian Maria Elena Buszek, that the more public the woman, the more available her sexuality, and Sorayama’s erotic female robots made the future female-coded available. His fembots not only eroticise technology but celebrate a culture that recognises women for their beauty and not their agency. Had Sorayama depicted erotic male robots and he’d ever become this famous?

The extensive objectification of women in pop culture explains why robots have feminine attributes as opposed to masculine ones, given how our society is at odds with male sexuality. In an article shared on Polygon, it reads, “It came as no surprise to me, as I imagine it won’t to many of you, that “girl” robots (…) are far more likely to appear as the object of their creator’s romantic or sexual interests; while masculine-coded androids are usually sons, not boytoys.”

For many, Sorayama’s erotic bots are not the subordination of women but their idealisation, free from patriarchy: strong, empowered, superior. While this may be true in many ways, it is suggested that female emancipation comes in hand with unattainable feminine body proportions and nonhuman capacities — a fictional character who lacks the faculties to exist outside our collective imagination.

While technology allows us to reimagine ourselves and explore human and nonhuman relations, it has also been used to highlight essentialist ideas of femininity and sexuality. Even though our culture longs to sexualise women, erotic images of female bodies are censored, considering it inappropriate content for the masses. Interestingly, this doesn’t apply to Sorayama’s Sexy Robots, posing the question of why we can fantasise over fictional female bodies but not over real ones. If something it’s true in this conversation, is that Sorayama’s work has uncensored female eroticism in the digital age.