What do you do when you don’t like what the government is doing to you or on your behalf? Join a political party? And if that’s not possible, then march together with others.

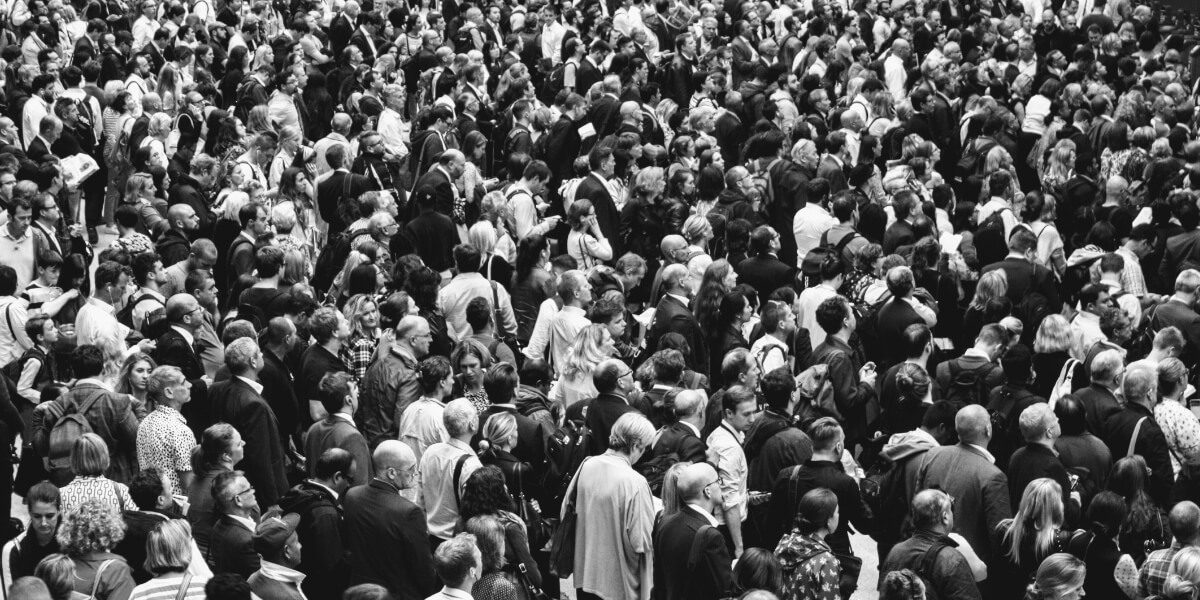

In recent weeks, I attended a protest and I was surprised to see the amount of parents pushing through the streets with children. The look on the children’s faces varied from cheerful to puzzled, uncomfortable, and aloof. Standing there in the cold, walking along with the masses and shouting in unison, I saw entire families with pushchairs join the thousands of people that sprawled over the streets.

Looking at all these people, all from different walks of life, I felt like sorting out the quality of the current demonstrations is rather hard to express or capture, and I wonder even more whether we’re protesting because we intend to change the atrocious course of political action or because we want to show empathy for others? While one doesn’t exclude the other, we’ve learnt from the protests against the war in Iraq, in 2023, that anti-war protests are often ‘unsuccessful’ — in the sense that they don’t stop the war.

But I think the value of protesting cannot be measured in terms of success.

When we take over public spaces to protest, our bodies — yes, those that are used as a nation’s workforce to produce wealth — become our physical and symbolic means of resistance. They contest social and political hierarchies by disrupting the regular rhythm of public spaces and transforming them into spaces of collective support, where we can together be enraged, sad, hopeful, and passionate.

To occupy the streets is to resist, because it is in those spaces when we realised that we are not alone, that we aren’t strangers — but allies. And to know that many others stand with us and think the same way we do gives us the hope that we can still coin a better future for us. After all, we all need that faint light that hope produces in dark times like these.

But I don’t want to romanticise the meaning of protests.

I think protests are, in principle, not only a collective affirmation in the face of doubt or denial, but they play a valuable moral function, which is the one to communicate publicly and unanimously, Not in my name. And making this statement feels like our moral duty, especially in times when democracy is exercised at odds with its own principles. Especially when governments justify their actions in our names. Especially when they wage wars with the money they collect from us.

Joining together in these moments is to demand accountability.

On 15 February 2003, the day that 30 million people across 72 countries went to the streets to protest, was the day a generation lost its innocence, as the biggest anti-war protest in history was ignored. Ever since, anti-war protests aren’t anymore an innocent act but a revelation that our political leaders are violent, not to call them criminals, and that our governments aren’t longer representative of their peoples.

No matter how much media outlets portray protests as ‘violent’, the truth is that no one can compete with the government in violence. But to resist, as Noam Chomsky said in an essay published in 1967, is a moral responsibility that cannot be dodged, even though is doubtfully effective.

It’s time to resist.