What Went Down at Paris Haute Couture Week

Fashion shows, particularly couture, are extravagant, somewhat experimental, somewhat traditional, and overall, an awe-inspiring and mesmerizing experience reserved for the privileged few. So what was it like to witness the couture designers’ playground this week? Kicking off with Schiaparelli’s show on Monday, the fashion week set the tone with a mix of praise and criticism, creating a memorable moment for the Italian house led by Daniel Roseberry.

Throughout the events, sustainability took center stage, as demonstrated by RDVK, while countless hours of manual work shone through in splendid embroideries showcased in Rahul Mishra’s collection. This couture week also symbolized the paradoxical nature of a stormy global economy and geopolitical confrontations, as Viktor & Rolf highlighted, juxtaposing the reality through their gowns. So, let’s delve into the highlights of the week.

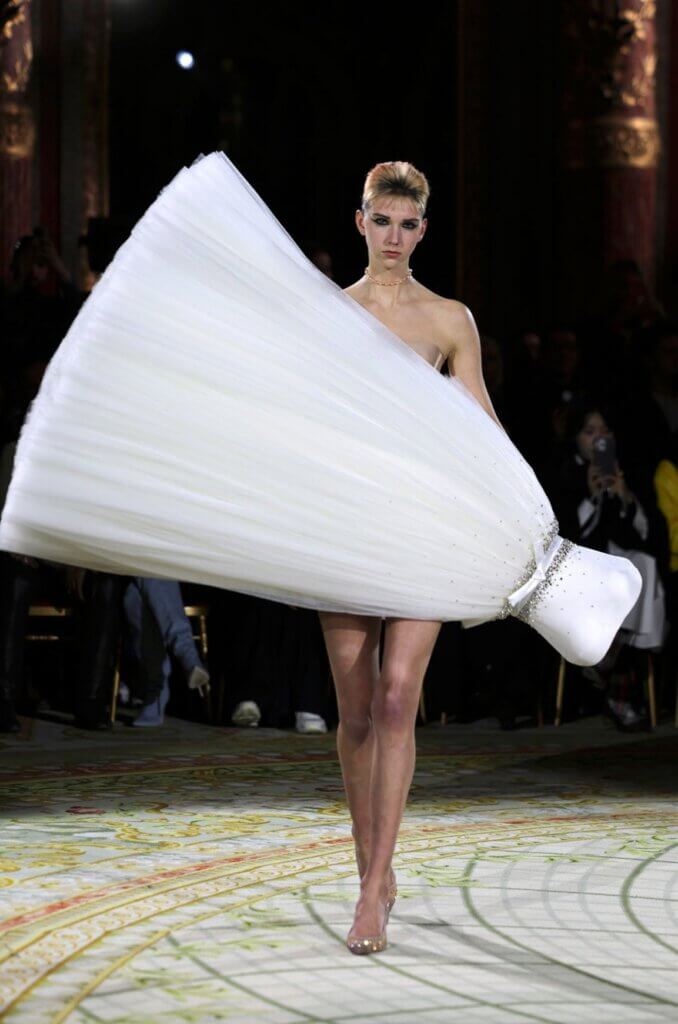

Viktor & Rolf

Viktor & Rolf’s collection revolved around irony, 3D technology, and inverted pieces. Gowns were worn upside down, seemingly parallel to their wearers, or tilted to the side, cleverly mirroring the current global state of confusion and displacement. The Dutch duo experimented with visual and auditory perceptions, challenging the discrepancy between appearance and reality—a paradox mirroring today’s world.

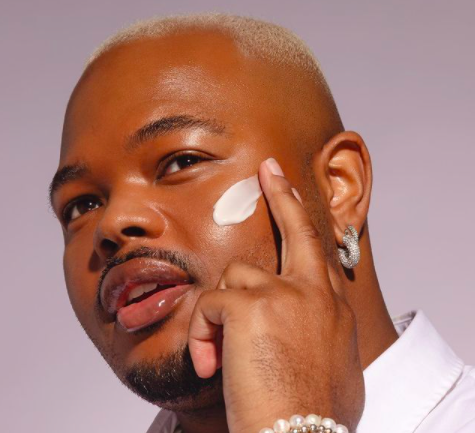

Schiaparelli

If “shocking” and “surrealism” are intrinsic to Schiaparelli’s DNA, Daniel Roseberry elevated these elements to a level that some found too literal. Shalom Harlow’s chest sported the head of a leopard, and Irina Shayk flaunted a lion’s head, completing Roseberry’s intended narrative of Dante’s Inferno. Naomi Campbell graced the runway with a lion, adding to the dramatic story.

While Roseberry’s collection featured astonishingly silhouetted trouser suits, tuxedos, and pieces exuding playful diversity of volumes and surrealism, the internet buzz focused more on the confusion generated by the animal heads, overshadowing the overall brilliance of the collection.

Dior

Maria Grazia Chiuri once again embraced female power and femininity in her showcasing efforts. This time, she paid homage to the iconic black dancer Josephine Baker, dominating Dior’s stage with a long black silk dress, a purple velvet gown, and a full cast donning hairdos reminiscent of Baker’s style.

Chiuri’s collection retained her signature floral appliqués on sheer fabrics. While predominantly sticking to a black and white color palette, she introduced muted green and silver accents.

Yuima Nakazato

Yuima Nakazato captivated audiences with shimmering fabrics sculpted into voluminous ruffles that gracefully wrapped around the body. These elements showcased Nakazato’s fantasy-driven aesthetics. His various textures, densities, and proportions were the result of his research trip to Kenya, where he encountered mountains of discarded clothing from Western countries. He collected and transformed these materials into ethereal and otherworldly pieces, paying homage to Kenya’s predominant style while adding his own daydream-inspired touch.

Ronald Van Der Kemp

For anyone doubting that sustainable fashion can be glamorous, a glance at Ronald Van Der Kemp’s couture would prove otherwise. With a decade of experience, Kemp employs radical recycling and repurposing practices, turning trash into treasure.

This season, he not only focused on the intersection of couture and waste but also created a disquieting entrance to the event. Thick curtains of smoke, disconcerting red lights, and unsettling clanging sounds guarded the path to the seats, perhaps symbolizing today’s turmoil.

Rahul Mishra

In this collection, Rahul Mishra ventures into the cosmos, contemplating its meaning and beauty. Just as the cosmos is vast, his collection exudes creative infinity. Dresses adorned with complex embroideries reminiscent of interstellar phenomena create a dreamscape in various forms. The mind-boggling embroideries required the expertise of over 1,000 artisans from Indian craft communities, selected based on principles of cultural sustainability.