Ever wished to pause everything and embark on a sweet sleep away from all duties, angst, and pain of life?

What if I tell you that if you were lucky enough, you could do so for as long as one year, letting yourself traverse drug-induced clouds of blankness dreams until the day you wake up to a brand-new world full of possibilities, colours, and sensations? Would you call it spiritual rebirth, or self-indulgence? Prescription for existential crisis, or culmination of the metropolitan dream?

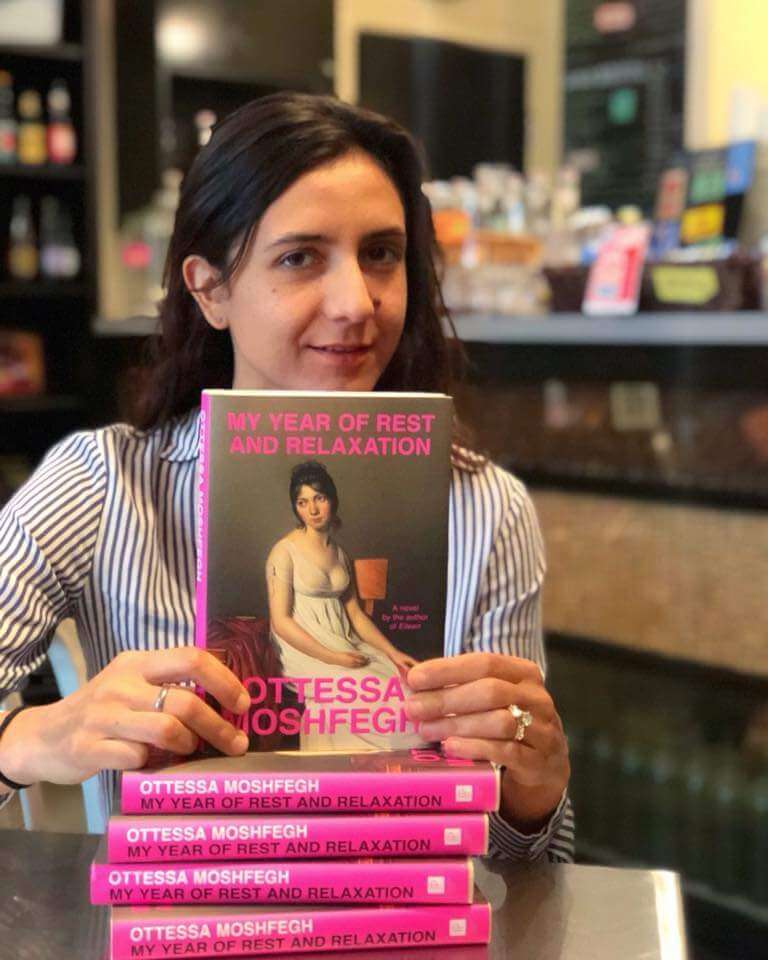

Sleeping for one year to shake off the weariness of being alive is the thought setting the foundation for the master plan of Ottessa Moshfegh’s main character in My year of rest and relaxation, a satirical novel published in 2018. The unnamed narrator, a beauty queen dwelling effortlessly at the top of the social ladder in New York, with all payments for basic living expenses set to automatic, hopes that a year of mental and physical reclusion will transmute her revulsion at life into a feeling of, erm — something better.

Or more precisely, that the world would finally turn into a place that is worth her existence. “When I’d slept enough, I’d be okay. I’d be renewed, reborn.”

The 26-year-old narrator, aware of the petty anatomy that underlies social relations, people’s aspirations, and self-perceptions, delves into the pleasures of hating supported by such social taxonomy. And so after majoring in art history, working in an art gallery where she barely did anything, and enjoying the social benefits attributed to being beautiful, wealthy, healthy, having good taste, and a spoiled attitude, the narrator willingly becomes addicted to antidepressants, anti-anxiety and sleeping pills, and anything else that helps her escape the noise from life.

“Things were happening in New York City — but none of it affected me. This was the beauty of sleep — reality detached itself and appeared in my mind as casually as a movie or a dream. It was easy to ignore things that didn’t concern me.”

Conveniently, the narrator finds Dr. Tuttle, a permissive psychiatrist who keeps her cabinet full of drugs, an assortment of downers that Moshfegh has wittily named, such as Infermiterol, along with other well-known sedatives. The indifference of the therapist to examine the actual causes and veracity of the narrator’s symptoms is only one more element in the web that sticks in, licks, and feeds the apathy of the main character.

Since the story begins, the narrator describes the nature of her relationship with Reva, her closest friend, and Trevor, her ex-boyfriend, which are tainted with contempt, based on typical heteronormative, abusive dynamics, revealing the lack of authentic, nurturing relationships, and deeper down, the irony of social injustice and white privilege.

“If I had been a man, I may have turned to a life crime. But I looked like an off-duty model. It was too easy to let things come easy and go nowhere.”

Reva, a “gym rat,” often shows up at the narrator’s flat with a bottle of booze and a monologue reflecting on the course of her life, interrupted by comments that address the appearance and health of the protagonist. The narrator, who distantly listens to Reva with some words of acknowledgment now and then, keeps snoozing in front of the films she’s been binging on over and over again. And so their relationship continues this way — uncommitted, uninterested, and remorseless.

But the narrator’s sleeping intervals raise red flags when she begins waking up and is dressed up, waxed, with packages of online shopping arriving at her door, and takeout standing on the counter of the kitchen. Even worse, with photos that prove her outings with personalities she dislikes and her phone’s call history recording outgoing calls to her ex-boyfriend, a banker at the World Trade Center who has a remarkable “sincere arrogance to back up his bravado.”

In refraining the alter ego of her subconscious from having a parallel life, one which her lucid self despises, the narrator sets an unbreakable cage for herself by emptying out her flat, leaving all payments on automatic, and inviting Ping Xi — a presumptuous artist represented by the gallery where she used to work — to use her as a canvas for any artistic project in exchange of keeping an eye on her basic needs.

“The third awakening marked nine days locked inside my apartment. I could feel in my eyes when I got up, the atrophy of the muscles I’d use to focus on things at a distance, I guessed.”

It was June 2001 when her year of rest and relaxation was completed. “I was alive.”

What could go wrong?

Nothing, really. Everyone’s life kept going, and when the narrator woke up, she went out and slowly sipped in the little pleasures of being alive. The stale air that had had her heart pounding coldly evaporated and she felt Reva had grown into her, even though Reva’s affection had visibly shrunk. But the completion of the narrator’s year-long project synced with an unforeseeable event that would mark the permanent end of Reva’s friendship.

(SPOILER ALERT***)

And here is where I’m gonna spoil the read. Ottessa Moshfegh was planning to address the 9/11 terror attacks in this novel but the focus quite shifted towards the story of a WASP brat. However, it all comes down to epitomising the pitiless social anatomy that protects, as if by default, the lives of some people over the others when Reva, who had been working hard to climb up the stiff, rocky mountain to success — and hopefully self-love, too — is relocated to a new office in the World Trade Center by her boss, a married man who dumped her after they had an affair.

All the other non-aspirational role characters of the story remain untouched, living in bliss — or existential pain, but living, safely.

Ok, that was a huge spoiler. But I’ve left plenty of room to delve into Moshfegh’s writing, whose style seamlessly echoes internal dialogues, contextualised despite the fact that the story is set two decades back. And although this novel doesn’t really have a plot, the side stories reveal sentiments of loneliness, loss, and escape and make this tragic, dark comedy a great representation of existential alineation in modern life.