In a literary world of diversity and myriad tastes, finding the perfect book can feel like navigating a maze of choices. For those who enjoy the eccentric and the enigmatic, and for devotees of Agatha Christie’s timeless mysteries, the search for literary satisfaction can be both exciting and daunting. Fear not, for this article is tailored to the peculiar tastes of “weird girls” and Agatha Christie aficionados alike. Here we delve into unconventional book reviews and recommendations, leading you through a maze of literary wonders that will capture your imagination and satisfy your craving for the strange. Whether you’re drawn to the uncanny or find solace in the classic whodunits, prepare to enter a world of literature where eccentricity reigns supreme and the spirit of Agatha Christie lives on.

For the fellow Weird Girls

There is an ever-present phenomenon hanging over literature, an inescapable obsession with the insane and alluring, crazy but beautiful female character. It is in the roots of Western literary culture, seen in the aforementioned “Medea” and Shakespeare’s “The Taming of the Shrew.” It dominates bestseller lists with titles like Gillian Flynn’s “Gone Girl” and Donna Tartt’s “The Secret History,” featuring leading ladies that exemplify this elusive trope. The weird balance between utter disgust and amazement with her character sticks with the readers – and the following books are by far no exception.

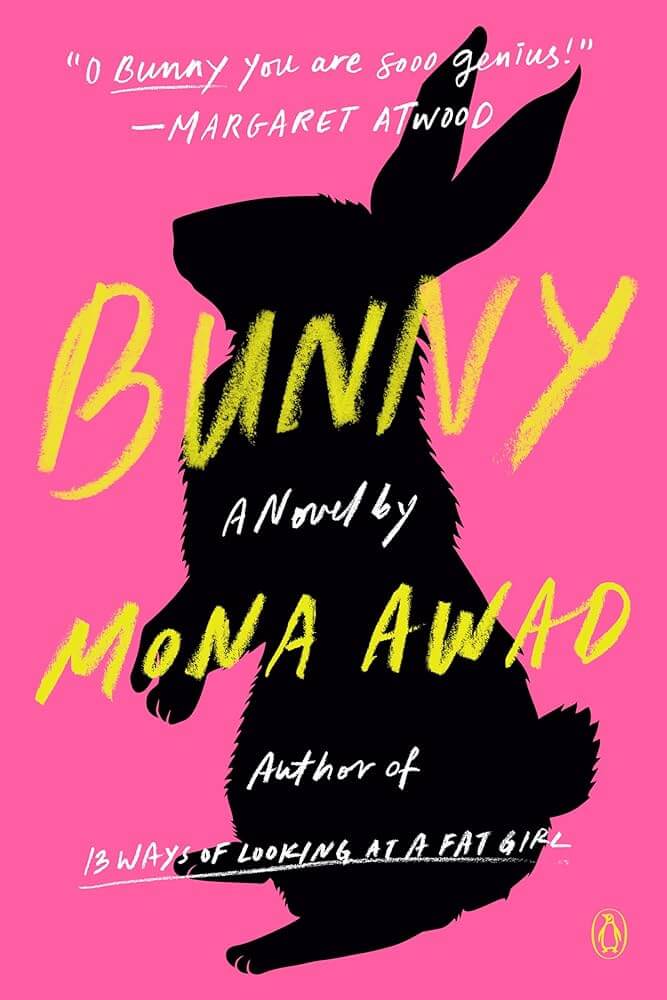

Ever heard of the phrase “A book should be like an ax”? Bunny by Mona Awad is exactly that and much more. Bunny is a truly bizarre, creepy, hallucinatory and hilarious novel. In brief, the novel follows Samantha Heather Mackey, a postgraduate creative writing student at a fancy New England University, called Warren University (I did not get the pun until my second read-through!).

Samantha cannot stand the clique of pretentious, fake-nice rich girls who make up her writing group, whom she has nicknamed collectively the Bunnies, after their pet name for each other. Then Samantha gets invited to one of their “Smut Salons” and indoctrinated into their group/cult.. and from then on things get really weird! Samantha is your fairly typical edgy, anti-social loner. She prefers her own dark imagination to spending any time with other people, the only exception being her best and only friend, Ava. With her mother dead and her father absent (reading between the lines, either in prison or on the run due to his financial scams), Samatha is isolated and lonely.

She keeps a barrier of snark and judgement up between herself and others. Most of the other characters she refers to nearly exclusively by a dehumanising nickname; from each of the four Bunnies (Duchess, Cup Cake, Vignette and Creepy Doll) to her professors (Fosco and the Lion). She accepts the invitation to join the Bunnies at their “Smut Salon” out of a combination of her loneliness and awareness that her isolation is ultimately not healthy for her mentally or academically.

As this whole novel is from Samantha’s point of view we are along for the ride on her mental rollercoaster, told in her own voice. To understand Bunny you need to understand Samantha.

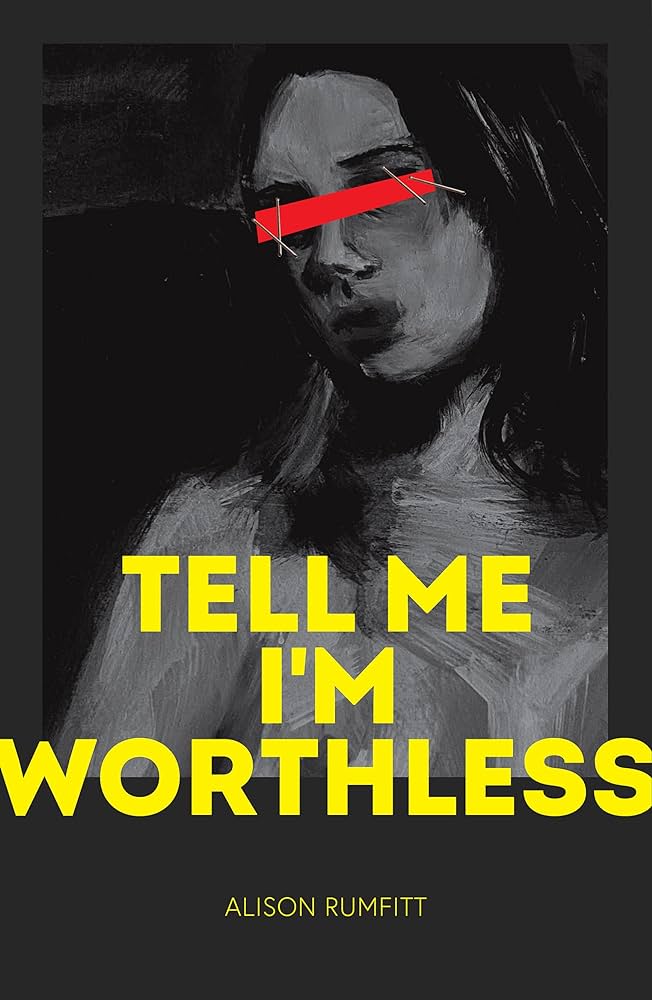

Alison Rumfitt’s Tell Me I’m Worthless however is a dark, unflinching haunted house story that confronts both supernatural and real-world horrors through the lens of the modern-day trans experience.

Tell Me I’m Worthless, the debut novel by promising young writer Alison Rumfitt, is a horror novel that not only has teeth but an intelligence and power to tear you to pieces and put you back together in a way that leaves you forever haunted, and glad for it. Seriously, this book is intense and while the content warning that precedes her grisly tale lets you know what you are in for, nothing can truly prepare you for how unsettling this is in the way it forces you to confront the violent and pervasive ideologies of fascism as it slimes its way through modern society. Drawing on a long history of horror and fairy tale literature, Rumfitt delivers a razor-sharp and very political haunted house narrative that explores issues of trauma and the trans experience under creeping fascism. The novel rotates between perspectives of Alice, a trans woman, and Ila (with an intentional choice to mirror their names), her former girlfriend that is now a public figure for trans exclusionary radical feminists, and the voice of the House itself, as the two women deal with the aftermath of them having entered the house years ago with their friend Hannah. Only the two of them walked out, both with conflicting memories of abuse from the other that occurred during their stay, and are forever traumatized and haunted by both figurative and literal ghosts. Tell Me I’m Worthless is an unrelenting horror festival that boldly pulls the reader through the hell of modern discourse and violent ideologies to explore the real-life horrors of queer life in the UK.

One Novel that reflects reality in its rawest form is also Cat Person by Kristen Roupenian. Not really an earth-shattering story: 20-year-old Margot meets Robert, almost a decade and a half older, at the cinema box office. They flirt for a few weeks via text messages and finally meet for their first real date. Margot quickly realises that Robert is physically repulsed by her. Nevertheless, she has sex with him that night, outwardly willing, inwardly alienated. When she breaks off contact a few days later, Robert begins to stalk her. “Cat Person”, the title of the short story by the American writer Kristen Roupenian, tells the story of a one-night stand gone wrong, as it probably happens more often than not: Unpleasant, but no tragedy. Nothing that should move the world. But that is exactly what this short story by a previously unknown author did. Immediately after its publication in the New Yorker in December 2017, ‘Cat Person’ became the viral hit of the year and a political issue. The text was shared thousands of times on social media and discussed at parties, in bars and on internet forums. Women used hashtags to share similar sexual experiences, and men defended themselves against their perceived degradation. Literature and reality intertwined as never before. The fire of debate sparked by a short story by a literary newcomer owed its heat to the #MeToo movement, which reached its peak in the winter of 2017.

Ottessa Moshfegh is the undisputed grande dame of Weird Girl Books. In the unlikely event that you don’t know what you’re getting yourself into with a novel by Ottessa Moshfegh, let’s be clear: it’s going to be nasty. For the rest of you, there is some truly fantastic nastiness this time around. There’s a placenta hissing in the fire after a birth, an old woman putting on horse eyes and seeing everything twice as big, and dry spider legs crunching between her teeth – a much sought-after meal in a drought. Ottessa Moshfegh’s stories are rightly revered for the beauty with which they tell of the terrible. Her novels and short stories are about outsiders and never-do-wells, addiction, madness and loneliness, and the sometimes unappetising physical reality they represent. In Lapvona, however, she takes this tendency to the extreme, drawing a hellish tableau of human monstrosity that slips into the fantastic. The village of Lapvona lies somewhere on fertile land in a time that loosely resembles the Middle Ages. In a hut on the outskirts of the village, the shepherd Jude raises his 13-year-old son Marek, whose spine is so crooked “that the right side of his ribcage protruded from his torso”. But he is not particularly interested in him, or in anything but his lambs. Marek, however, is happy when Jude beats him half to death again, believing that the pain “reveals his father’s love and compassion”. Marek’s mother, whom Jude kept as a sex slave for a time, ran away the night Marek was born; she is dead, the shepherd tells the boy, forcing him to keep looking at the supposed bloodstain on the floor of the hut. High on a mountain above them lives Prince Villiam, ruler of Lapvona, who starves the village and regularly raids it. When Marek kills the prince’s son, who is his own age, on a hike, the shepherd sees his chance to get rid of the boy for good. Villiam would surely condemn him to death. But the prince, completely detached from reality, is entertained day and night and regards everything as a production for his amusement. He finds the “monkey theatre” and the “skilful performance” of his sobbing wife very appealing. In fact, he finds the “crippled thing” Marek so entertaining that he quickly orders the boys to be swapped and Marek to be kept as his son from now on. Needless to say, this is not an ascent to a better world for Marek, but merely to another ring of hell. The scene is probably the most absurd in a book full of absurd scenes. Lapvona switches so suddenly between precise descriptions of corpses and grotesque humour that it could be described as splatter slapstick. And it’s really funny at times. Moshfegh unfolds a round dance of coincidences, lies and perfidy, and for a while we enjoy the imaginative disgust, the trenchant dialogue and the typically unsentimental descriptions of the human abyss.

Lastly: Dizz Tate’s debut novel, Brutes, begins with the mysterious disappearance of Sammy Liu-Lou, the daughter of a famous televangelist and a rebellious figure with a shaved head. As her mother confronts the empty bed, a single question echoes through the fictional Florida town, teasing the placid surface of the lake at its centre: “Where is she?”

Despite the frustration of Sammy’s enigma, the novel pivots away from her narrative, focusing instead on a group of eighth-grade girls who peer through binoculars from their bedroom windows, scrutinising not only Sammy but all the residents. These girls, Tate’s ‘brutes’, collectively take on the role of the book’s sardonic yet vulnerably naive first-person plural narrator. Sammy’s disappearance becomes just another distraction in a literary house of mirrors that deliberately skims the surface of the dubious (and occasionally supernatural) occurrences in this swampy, theme park-adjacent landscape. Amidst the unfolding search party of evangelical groupies, the girls introduce a suspicious cast, including Sammy’s caricatured, villainous best friend Mia, who, along with her mother and a man named Stone, recruits kids for their talent show, Star Search.

“Brutes” is underpinned by a central idea: “that the stories we told were not just stories, but creatures, both dangerous and true”. While the narrative explores chilling revelations, it is tied to the concept that narratives are living entities. In this magical realist, twisted Florida fairy tale – a Lynchian reimagining of The Virgin Suicides – trauma manifests itself in unpredictable ways. Each girl aspires to be the protagonist, but glimpses of their futures reveal the high price of stardom.

Agatha Christie doesn’t stand a chance

Agatha Christie, the undisputed queen of murder mysteries, had a knack for killing characters with more style than a fashion designer at a crime scene. She didn’t just write whodunits; she wrote ‘whodiditbetterthanyoueverthoughtpossible.’ Forget ‘Clue’—Christie’s mysteries were the original game-changer, where the only crime was not reading one of her books. But she may pale in comparison to the English author Alex Michaelides.

“The Silent Patient” (the first book he wrote) is a psychological thriller that grips its readers from the very first page and takes them on a rollercoaster of suspense and unexpected twists. The novel introduces us to Alicia Berenson, a renowned painter who seemingly has it all, until one day she is found standing next to her husband’s dead body with a gun in her hand. The catch? Alicia doesn’t utter a single word after the incident, rendering her seemingly mute.

The strength of Michaelides’ writing lies in his ability to create a tense and mysterious atmosphere throughout the narrative. The story is narrated by Theo Faber, a criminal psychotherapist determined to unravel the enigma behind Alicia’s silence. As he delves deeper into her past and the events leading up to the tragic incident.

What sets this novel apart is its unexpected and jaw-dropping conclusion. Michaelides masterfully constructs a narrative that challenges readers’ perceptions and keeps them on the edge of their seats until the very end. The cleverly woven plot and the shocking twist make for a satisfying and memorable reading experience.

“The Maidens” however appears to be a direct continuation of the first book, even if the stories are completely different. The story follows Mariana Andros, a group therapist in London, who becomes entangled in the investigation of a brutal murder at Cambridge. The victim is a young woman named Stella, and the primary suspect is Edward Fosca, a charismatic and enigmatic professor with a group of devoted female students known as the Maidens. As Mariana digs deeper into the case, she finds herself drawn into a web of secrets, obsession, and the haunting echoes of a traumatic past.

One of the strengths of “The Maidens” lies in Michaelides’ ability to create a rich and atmospheric setting. The ancient halls and traditions of Cambridge University provide a compelling backdrop, adding an extra layer of intrigue to the narrative. The exploration of Greek mythology and its influence on the characters adds a unique and engaging dimension to the story.

The character development in “The Maidens” is well-executed, with Mariana serving as a complex and relatable protagonist. The relationships between the characters are skillfully crafted, and the tension builds steadily as the mystery unfolds. Michaelides excels at creating an atmosphere of unease, keeping readers guessing and questioning the motives of each character.

Similar to “The Silent Patient,” the novel is marked by a surprising twist that reshapes the reader’s understanding of the narrative. The pacing is generally well-maintained, with the author skillfully balancing the tension and revelations throughout the story.

Last but not least: The Fury.

Unlike the first two books, where you always felt some kind of connection to the protagonists, you feel one thing in particular towards the main character: disgust. Elliot Chase is highly unlikable and anything but sympathetic. The author opts for a very meta style, with Elliott constantly addressing the reader, side-eyeing his audience, and acknowledging his own flaws as a narrator. He assures us, that although it’s a story about seven people trapped on a beautiful but isolated, private Greek Island called Aura, that it ISN’T an “Agatha Christie” whodunnit with a baffling crime, and a clever solution. It’s more of a “why dunnit”-a character study of sorts.

The narrative centers around Lara Farrar, a beloved Hollywood luminary who has recently bid adieu to her illustrious career at the age of forty. She extends an invitation to her closest confidantes, Kate and Elliot, to join her on a secluded Greek Island—a cherished gift from her first husband. Alongside Lara are her devoted husband, Jason, who shares an uncanny connection with Kate, and Lara’s son, Leo, from her previous marriage. Leo harbors dreams of becoming an actor, much to his mother’s chagrin. The ensemble is rounded out by Agathi, the steadfast babysitter, assistant, and cook, and Nicola, the caretaker whose lingering glances at Lara do not go unnoticed.

The tale commences in the tradition of a classic, locked-house mystery—a group of friends seeking solace on a secluded island. However, beneath their seemingly unbreakable camaraderie lie hidden secrets, unspoken resentments, and simmering frustrations, setting the stage for a tragedy that will irrevocably alter their lives. A murder takes place, and the island’s harsh weather conditions leave them marooned. There is no evidence of an outsider’s presence, no boat, nor any indication of escape, making it clear that the killer must be among them. Yet, the motive remains elusive, and the veneer of friendship begins to peel away, revealing deeper, darker truths.

What begins as a complex melodrama gradually metamorphoses, evolving into various genres: from romance to psychological mystery, and ultimately culminating in a crescendo of a heart-stopping thriller blended with a poignant tragedy. My apologies if this review appears somewhat enigmatic, for “Fury” is a narrative that defies easy summation. To truly appreciate it, one must embark on this journey without preconceived notions, surrendering oneself to Michaelides’ evocative, mind-bending, and cryptic narrative style.

The Wife Between Us falls into the same category of muder-mistery-greatness. The story revolves around the seemingly perfect marriage of Vanessa and Richard. However, as the plot unfolds, the reader is taken on a journey through a labyrinth of secrets, deceptions, and unexpected revelations. The authors employ a dual-narrative structure, providing different perspectives on the same events, adding layers of suspense and intrigue.

The character development is exceptional, with the protagonists revealing hidden depths and motivations that challenge initial assumptions. The narrative skillfully explores themes of love, betrayal, and the complexities of human relationships. As the story progresses, the lines between truth and perception blur, creating an immersive reading experience.

What sets “The Wife Between Us” apart is its ability to keep readers guessing until the final pages. The unexpected twists and turns create a sense of urgency, making it difficult to put the book down. The authors’ clever storytelling and well-crafted suspense make this psychological thriller a standout in the genre.