SENSORY MOUNTAINS – SAMIRA MAHBOUB

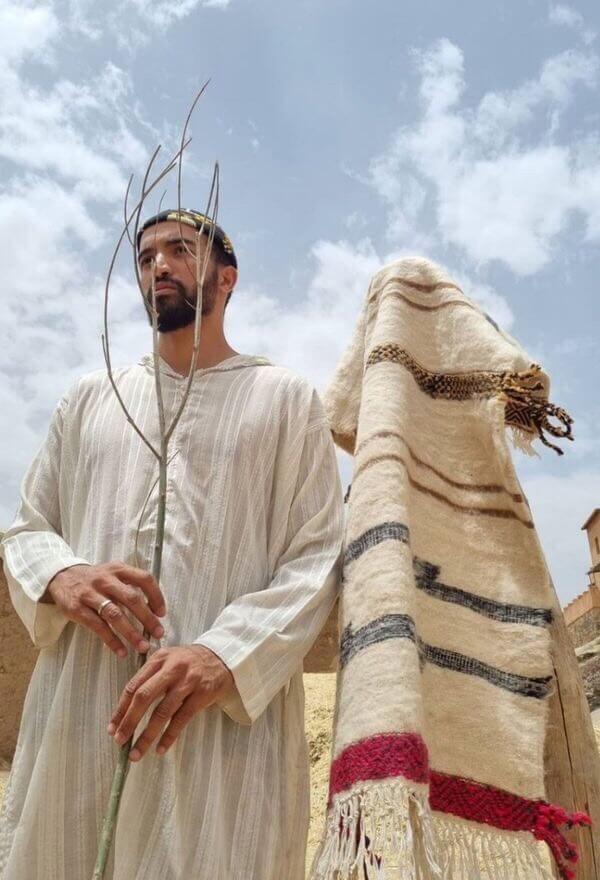

Where the sandstone slopes transition into valleys. Two eyes between the juniper trees, dreaming about desert days. A velvet Kaftan in green and gold, wafting to Moroccan Gnawa Music. When I met Samira for the first time her hands were shimmering, adorned in traditional jewellery. Samira Mahboub is an entrepreneur, sociologist and performance artist. Together with Zaid Charkaoui, she co-founded Limala. Celebrating Moroccan’s artisanal culture through “Slow Manual Labour” with handcrafted rugs from the Atlas Mountains. Samira did her Master’s in Gender, Media and Culture focusing on postcolonial theory, intersectional feminism, and affect theory. Today, she uses her voice to talk about decolonizing our mind and gaze. Reclaiming the indigenous language and giving power back to the people and communities. When Samira speaks of cultures and identities, she never un-sees the privileges that are wrapped around the act of examination. Her words build the bridges that connect identities.

What is Morocco for you?

A sense of belonging. When I exit the plane, I can smell the air. The freshly brewed mint tea and the couscous from my mother in law, cooking from a distance. A physical reaction and emotional experience. A feeling that sets from the heart unfolding to the chest. Floating through my bones. Standing in a country where I belong. There are tears in my eyes.

What is the identity of Limala becoming?

A loud and conscious celebration of Moroccan artisanship and culture. Standing hand in hand with Zaid immigrating to Germany, our personal love story and the beginning of Limala. The sieve that collects our longing for Morocco. My husband Zaid was born and raised in Morocco and I am half Moroccan-half German, born and raised in Germany. We wanted to find the artisan communities behind the Amazigh rug making. Knowing we had to go through the Atlas mountains and villages. The country that holds many stories knotted into rugs. We currently work with two communities from two different villages. The Boujad rugs are made by a family from the Boujad region, where Zaid is rooted. A family business structure in an intergenerational shared labour. Entwining layers centimetre by centimetre.

The indigenous word — the original word — how the people refer to themselves, is “Amazigh.” And the plural is “Imazighen,” which means free humans.

SAMIRA MAHBOUB

Can you tell us about the problematic origin of “Berber” and reclaiming the indigenous word “Amazigh”?

It is a problematic word, because it originates from a neo-colonial violent background imposed by the colonisers. Coming from the Latin-Greek word “Barbarius,” which translates into the English “barbaric.” A foreign determination, imposed and named by the colonisers. Respecting the original meaning of it, you would say “the rugs from the barbaric people.” The indigenous word — the original word — how the people refer to themselves, is “Amazigh.” And the plural is “Imazighen,” which means free humans. A vision for Limala is to reclaim the word and make it more accessible to the people outside of the Amazigh understanding and community.

How can we start reclaiming the indigenous language?

There is a different focus for people living in the diaspora and country itself. Talking about reclaiming the indigenous word Amazigh on social media, I received good criticism from the Imazighen community within Morocco. Saying that while I am busy reclaiming, it does not change the multi-layered problems of their reality. Thinking through theoretical frameworks is crucial in the academic realm, to bring attention to the gravity of language. Where yes it matters, but there are harsher and more cruel realities minority groups have to face. That I am sitting here in the ‘Global North’ of Germany being Moroccan and white-passing, talking about the word Amazigh: There is by itself a privilege, because I didn’t have to struggle to liberate myself from specific forms of oppressions. We should not forget the privileges that sink into this act of examination.

The individual placed above everything else, validated through the rhetoric of healing the self. Performative spiritualism is a dangerous trend that has co-developed with the rise of social media.

SAMIRA MAHBOUB

Do you believe humans exist in groups or in the individual?

There is the obsessed idea of the individual from the ‘Global North’ versus the collective. An integral structure of the neo-liberal capitalist society. The idea of “I come first,” like right now with the “new found spiritualism”. People, mostly white, from the ‘Global North,’ privileged in a specific class, are discovering their spiritualism through appropriation without further knowledge or prospect. Going to specific parts of the world, learning and profiting from intellectual property. Then making money by teaching others meditative cultures. If you look close enough, it can be a camouflage coat around selfishness and legitimate narcissism. More and more people are using narratives, such as “me and my healing.” The individual placed above everything else, validated through the rhetoric of healing the self. Performative spiritualism is a dangerous trend that has co-developed with the rise of social media. While it is important to look after yourself, It needs to be balanced with care. So do you give back or are you just taking?

The fashion industry saying ‘yes to the headscarf’ after not acknowledging women with hijabs for decades – how is this happening?

The hypocritical way in the fashion industry and the celebration of the ‘headscarf’ is a verbal kick in the face to all the women who are veiled. So to what kind of headscarf do you say yes? Experimenting with different kind of veils since decades without tolerance, respect and inclusion for Muslim clothing traditions. A world where anti-Muslim racism are so present politically. And where Islamophobia is omnipresence. Women are denied to wear the burka or burkini or veiled women have to face social consequences and violence. Denied to be teachers with a lack of access to certain professions. A western obsession and desire to unveil the headscarf since colonialism. With the headscarf and hijab, as one of the primary targets of hate crimes and anti-Muslim racism. There are a lot of racist attacks that people have to face on a daily basis. The media is still mass manipulating, marginalizing and dehumanizing people with a Muslim and Islamic background. Fashion emerges as a window where certain things are ‘doable’ and ‘celebrated.’ Shaped by white identities and bodies removing it from any spiritual or religious context. This hurtful display of exclusion is just one.

When does language become political?

Language is always political. As a sociologist, I know that language structures and produces reality. Ideas are never neutral or natural. Looking at differences always produces dichotomies. The second you announce binaries, you create a hierarchy with ideologies. While modernity is tied to the ‘Global North’ — caught up with rationality, progress, and development — the ‘Global South’ becomes coded as the opposite with traditions and inferiority. A product and legitimation for using the term ‘civilised’ vs. ‘uncivilised.’ Routed in the system of white supremacy and concepts of dehumanisation. One of our responsibilities today is to unlearn what we have unconsciously learned. To struggle with uncomfortable questions and critically reflect on the systems of oppression. Our ideas of solidarity and justice need to be intersectional.