I was five years old when I got my first piercing. Like many kids of my generation, I quickly grew tired of the “stick-on” earrings you could buy at the dollar store. So I basically begged my mum for real piercings and after a while she finally gave in. That was the beginning of my personal journey with body piercing. Even my brother gave me a gift card to a local piercing studio for my fourteenth birthday.

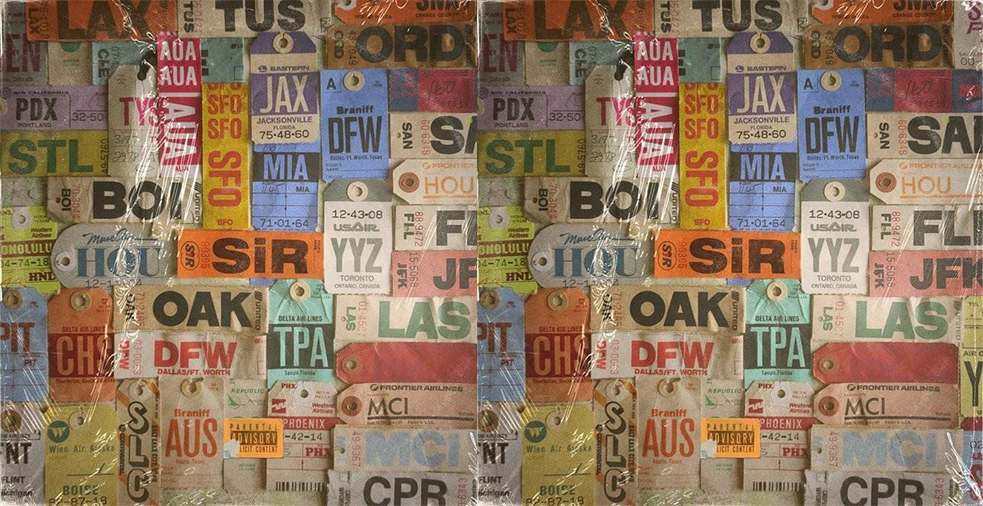

But not everyone’s parents were so nonchalant about their children’s and teenagers’ body modification choices. Giving parents a scare with body piercing was something of a rite of passage. Whether it was insisting on a lip piercing after the release of Christina Aguilera’s ‘Dirrty’ or coming home with a pierced navel to recreate Britney’s My Prerogative album cover, pop culture was awash with teenage piercing inspiration. While that era is now known as the golden age of modern piercing, today’s trends show that body bars, rings and studs are far from out of fashion.

Piercings have a long and rich, cultural and spiritual history. From the polar regions to the pacific islands, they go further back than Ancient Egyptians. Subtle studs were worn in the ears of ancient Romans, and certain Romans also had their penises pierced; seen as a way to control sexuality, penis piercing was believed to prevent slaves from reproducing, athletes from using up precious testosterone, and singers from keeping their voices high. Before the arrival of the Spanish in Mesoamerica, artisans made jewellery for piercing en masse from jade and organic glass. Even in the British Isles, indigenous people wore earrings before the days of the Roman invasion.

It was the ideology that came with the Romans that proved to be the greatest obstacle to piercing’s progress: Christianity. Seen as pagan and subversive, piercing became a threat to Christian values. But notions of acceptability ebbed and flowed over time. Like many hip 17th-century creatives, William Shakespeare had his ear pierced – but just 50 years later this was considered wildly seditious. As the British marauded the globe, piercings became another way for colonialists to assert their supposed superiority and use difference as an excuse to commit atrocities. Take India, where some Hindu worshippers had pierced their skin with hooks for thousands of years to ward off smallpox and honour deities. In fact, it was an Orientalist fascination with Indian women that catalysed the spread of nose piercing in the West. It began with a French artist called Mademoiselle Polaire. With a waist manipulated down to 14 inches, nose rings and a pet pig, she was a singer who marketed herself as ‘the ugliest woman in the world’ in the 1910s and 20s – problematically, her look included the use of a South Asian-inspired nose ring to appear more exotic. Fast forward to the 1960s, India was now independent, free love was flowing in the West and young hippies were starting to travel the world. Nose rings were back in fashion. An obvious mimicry of the practice of South Indian women piercing their noses. Western women wanted to make it fashionable.

But the practice was still inextricably linked to subcultures, and the procedures took place mostly underground. Most people pierced themselves or had a friend brave enough to do it for them. Safety precautions varied, resulting in many infections and inappropriate placements. Change came in 1975 – The Gauntlet, staffed by early members of the BDSM and S&M community, was the first piercing shop in the US. It would be these groups and the punk community that would make up the first clientele. For them, piercing was a way of signalling their affiliation to their communities.

Thanks to the pioneering piercers at the Gauntlet, piercing was safer and easier than ever. But not everyone was on board. Many parents in the 90s and 00s protested at home against their children getting piercings. It went so far that there was a flood of sensationalist articles about the horrors of piercing. The controversial nature of the practice is part of what makes it so appealing, especially to teenagers. Like any other youth culture, piercings were part of a form of self-expression and can feel rebellious. But it also helped people find a sense of belonging and identity. In a post-Aerosmith piercing culture, this group of pierced people now consisted of supermodel trendsetters like Naomi Campbell, who had her navel and nipples pierced by British piercer Teena Marie, and pretty much every woman in a music video at the time.

But just like today, piercings aren’t always visible. In the 90s and mid-2000s, genital piercings became popular and boundaries were pushed. But by the 2000s, the stigma had lessened. Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera and all their teenage followers flaunted Y2K diamonds in their bellies and noses.

Piercings permeated all areas of pop culture, becoming increasingly elaborate and even making their way into couture. In 1997, models walked the Christian Dior catwalk wearing oversized ‘maharajah earrings’ and in 2012, a Givenchy campaign featured models with chandelier jewellery in their septums and earlobes. Today, pierced models graced the runway at Chanel’s Cruise 2024 show and Valentino’s Autumn/Winter 2023 show.

So to sum up, piercings are an old trend that won’t be going away any time soon. So maybe it’s time to make your next appointment with your trusted piercer? What about nipple piercings?