Art in its many forms—paintings, dance, performance, music, and countless others—is an act of expression. While there are many complex definitions of art, at its core, it is the ability to create and communicate. But who decides who gets to be the audience? And more importantly, who gets to participate in the conversation?

Here’s Your Invite (Access Not Guaranteed)

As we perceive it today, the art world remains largely an exclusive space. Shaped by hierarchies and gatekeeping mechanisms, it is often still a predominantly white and elite domain. Access is imposed not only by financial means but also by social structures that favor certain groups over others. A significant reason for this is the lack of representation—both in terms of the artists showcased and the narratives presented in exhibitions. Additionally, barriers such as limited accessibility, high entrance fees, and the absence of diverse artists who create space for new conversations, continue to exclude marginalized communities.

Art is meant to be a reflection of society in all its complexity. It is supposed to challenge norms, provoke thought, and give space to those whose voices are often drowned out.

Street Art: The People’s Gallery

Despite these challenges, there are communities, museums, and even entire cities that are actively reshaping this landscape. They are creating spaces where art is not confined to the walls of galleries or dictated by academic discourse, but instead presented as a natural part of everyday life.

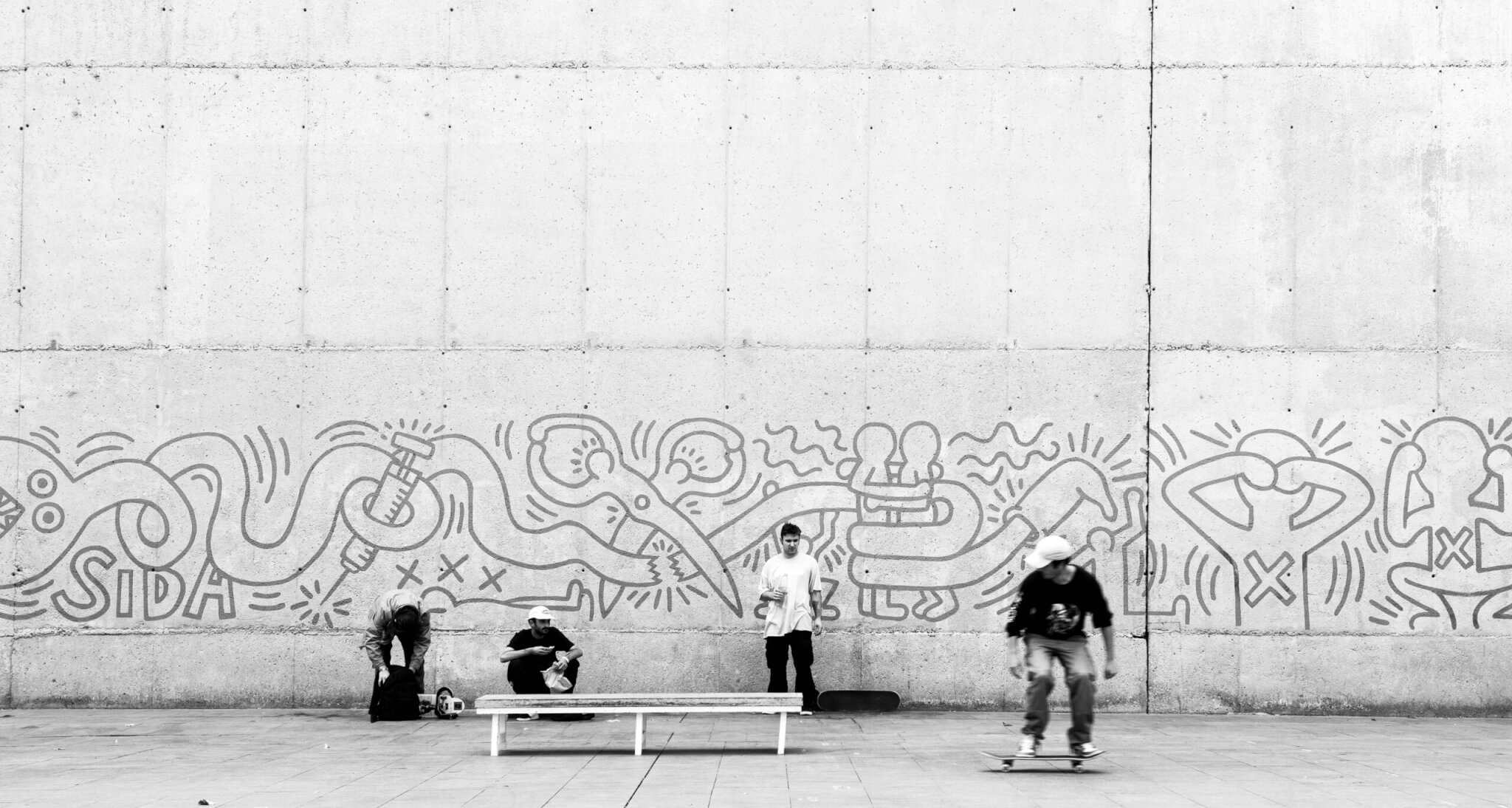

During a press trip to Prague, I was reminded of how simple yet effective accessibility in art can be. A local guide leading our tour pointed out the numerous art installations throughout the city. Works that were not hidden behind entrance fees or walls but spread amid urban life, available for residents and visitors to engage with. These public artworks, ranging from sculptures to murals, turn the city itself into a gallery. This makes art an integral part of the streetscape rather than an experience reserved for an elite audience to enjoy.

Street art has long served as a medium of resistance and accessibility. Pioneers like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring used public spaces as their canvas, bringing art to those who might never step into a traditional gallery. Their works, often filled with social and political influences, redefined the boundaries of artistic spaces. More contemporary figures like Banksy continue this legacy using street art as a tool to challenge authority and provoke discussion beyond four walls. Unlike conventional galleries, where exclusivity is often the norm, street art fosters a sense of community ownership—anyone can view, interpret, and interact with it.

From The Community, For The Community

The presence of marginalized voices in traditionally exclusive spaces is rarely supported by active inclusion. It often stems from the efforts of communities advocating for themselves and others. When institutions fail to open their doors, these communities build their own. One example is the Muslim*Contemporary Festival, co-founded by Austrian artist Asma Aiad. This multidisciplinary, anti-racist, and intersectional-feminist festival in Vienna has been instrumental in creating a platform for marginalized artists, promoting visibility and accessibility. By showcasing diverse narratives and perspectives, the festival challenges the Eurocentric lens through which art is often presented and redefines what an inclusive art space can look like. It is a reminder that representation is not just about presence, it is about active participation and the ability to shape artistic discourse.

Change can also come from within institutions, demonstrated by Tayla Myree. As an American historian, artist, and researcher based in Vienna, Myree dedicated projects to highlighting underrepresented narratives in the art world. Among her many contributions, she has been leading the Turning the Page. Representations of Blackness tour at The Belvedere Museum in Vienna. This guided tour, in conversation with art mediator Paul Walther, dives into Black representation within the Upper Belvedere’s collection. Beyond simply acknowledging the presence of Black figures in art, the tour initiates critical discussions about the erasure, misrepresentation, and historical positioning of Black individuals in European art history.

Initiatives like Myree’s tour address these overlooked narratives by disrupting the traditional frameworks through which art is analyzed and appreciated. They challenge institutions to confront biases and historical omissions, pushing for a more inclusive understanding of artistic heritage.

No Invite Needed: Art is for Everyone

The question of who gets to experience and create art is ultimately one of power. While progress is being made, accessibility requires more than surface-level inclusion. It demands a structural shift in how art is valued, curated, and shared. The art world cannot continue to operate as an exclusive club, claiming to represent the diverse human experience. It must embrace the diversity of voices and stories beyond its traditional boundaries.

Art belongs to everyone. The true challenge lies within ensuring that the spaces where it is created, displayed, and celebrated reflect that truth.