Anyone interested in synthetic biology and art has most probably come across the name Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, and that is because the artist’s body of work has been shedding light on the ways emerging technologies – those that are lifelike or engineering life in some ways – can redefine life and our relationship with the natural world.

Daisy’s earlier work was highly influenced by the master’s course Design Interactions at the Royal College of Art, which was very focused on using fiction to think about the future and the implications of emerging technologies. And so projects like Resurrecting the Sublime, The Substitute and Machine Auguries – her first U.S. solo exhibition currently held at the Toledo Museum of Art – were situated in the future, as a reflection on the present.

However, as we talk, Daisy speaks about how her work in the last four years has become much more about the present, about dislocating from the future, about thinking about parallel worlds and not being caught up in a temporal discussion. This shift is palpable in Pollinator Pathmaker for the LAS Art Foundation currently placed at the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, which hints at the way Daisy’s new work is now focused on empowering people with the tools to acquire agency, as opposed to using biotechnologies to manipulate the natural world to serve human purposes.

And even more, Daisy asserts, her aim is to look at those technologies to ask questions about life itself and nature, looking at the different value systems between why we value one more than the other and why we value innovation all whilst neglecting and destroying the natural world that supports us and enables us to exist. Ultimately, asking, why are we more interested in creating artificial life forms than protecting existing ones?

Hi Daisy, it’s really nice to talk with you, thanks for making time for this call! I’ve come across your work in many different ways and I find fascinating the trajectory of your work and the way it investigates the meaning of life using emerging technologies. As it deals with technologies of the future and the natural world, what does the future for all living species look like?

I don’t think it’s great.

I think we are on a path of destruction of the natural world and of ourselves, given the current living conditions that we enjoy. What we’ve seen in the last days, weeks and past two years is absolutely terrifying. And I think it’s a distraction to think that technological solutions are the answer to that. The answer is political, social and economic. Above all – political.

I have spent a long time working in or being embedded in bioengineering at the beginning of my career, some 10-12 years, in West Coast and Silicon Valley area, Stanford and MIT as well, and the idea that technologies can just be applied to create solutions for something that is much bigger is dangerous. In fact, because the work of changing our own lives, attitudes and societies is much harder.

So I’m not particularly positive about the future, but at the same time, I think that humans are hopeful animals and in a way that’s part of the problem. We have the predisposition to hope that things could be otherwise, that long-term doesn’t matter, and that short-term survival is what we’re programmed to. Hope is important, though, we shouldn’t just give up, you know. But also, serious change is unlikely to happen and that disturbs me every day.

I find it interesting that you’ve mentioned hope as part of the problem, and I guess, of the solution too. Which project feels to you to give you hope for the future?

I’m curious what you think! In theory, Pollinator Pathmaker is very exciting. Working with LAS Art Foundation and the Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin on a DIY program that both institutions have been able to invest in and develop with us. We haven’t been able to do that yet in the UK, just didn’t have the capacity and the funding to do that. So it’s really exciting for me to see the true intention behind the work starting to emerge.

The most brilliant thing is seeing the switch from being in front of your screen using a digital tool to getting outside and spending time and resources in something like this is a hopeful act. It’s saying that there is another way of being, another way of acting and another way of thinking about value. And that to me is hopeful. I think this is the most hopeful of all the pieces I’ve made – or the least cynical.

How was it to bring the Pollinator Pathmaker, full of living organisms, to the Museum für Naturkunde?

The space at the Museum für Naturkunde was so sad-looking and now we’ve brought the forecourt of the museum to life. The museum, a natural history museum, is a complicated place in itself as it’s full of things that have been killed and collected so that we can study them. So to bring life to the outside and have the space where the scientists are studying it, recording what insects are visiting, and the public can be part of that and see that happening and enjoy it is really powerful, to bring life to a place that is full of things that are no longer alive.

It’s interesting that humans seem to like flowers somehow, we’ve evolutionarily adapted to like them, even though they’re not of direct benefit to us. In fact, flowers are sex organs for other species, and so the Pollinator Pathmaker is almost an artwork about sex – it’s about insects helping plants have sex and insects having food and getting drunk on nectar. It’s a pleasure artwork.

And it has found its home in Berlin! But what happens to those organisms once the time of display is over?

So the plants are going to be there for three years, after a year of bureaucratic delay. The plants that are used are perennial plants, so they live generally for 3 to 5 years. Everything at the end will be reused and will be given away. So it will live on but in different places, in a different format. That’s also a very interesting thing about creating living artworks – they can reproduce and grow.

As I’ve mentioned before, for me, the most interesting project is Resurrecting the Sublime, and I feel like it has a completely different direction from Pollinator Pathmaker. Sublime is about bringing the past into the present – recreating the past. And Pollinator Pathmaker is basically about today. Your work undergoes a shift from locating itself in the future to being in the present. How come?

Resurrecting the Sublime goes alongside a few different works with Machine Auguries and The Substitute. There’s sort of a trio about loss and recreation and the impossibility of recreating something. The natural world is not something that can be copied 1 to 1 and replace what is lost, simply because an animal or a plant is not an isolated object. It’s situated in a place, in an ecosystem at a particular time.

Pollinator Pathmaker was a response to that trio of works. With this work, I wanted to think about agency. Going into a museum and experiencing something like Machine Auguries, which is currently on show in Toledo in the US, is going into a space isolated from the natural world and listening to the recreation of a lost or soon-to-be-lost dawn chorus. There, you feel an experience of loss. It’s like Resurrecting the Sublime – the thing is already lost.

In Machine Auguries, the bird species are endangered, and while there’s still stuff we can do, there’s a dislocation between experiencing the work and then stepping outside and doing something about it. What is that step? My responsibility as an artist is to actually empower people to do something. Or is it just about evoking emotion and connection?

Pollinator Pathmaker does something quite different and it gets into this idea of agency. Reducing my consumption or changing aspects of my life is very difficult. I’m baked into a system and the little changes I make are good, but that’s not enough. Pollinator Pathmaker, again, is not trying to provide a solution. It’s not going to solve the pollinator crisis, but it does give us tools to refocus our attention, to connect with the natural world and to actually be doing while thinking. It’s a bodily experience in a different way.

Let’s talk more about the idea of agency. How does the audience gain agency through Pollinator Pathmaker?

So the idea, rather than create a garden for ourselves, which is what the history of civilized humanity has been doing, is to create something for other species. What I want people to do when they create a garden using the algorithm is to be transformed from consumer or designer to caretaker.

I’ve planted my own DIY Edition at home and I’ve never really gardened before, and suddenly I’m responsible for keeping this thing alive. I’m responsible for maintaining it and learning about each plant. It’s me observing the real audience of the artwork, who are the insects and the plants interacting with the insects.

This idea of having agency is that now I know more about gardening and about spending time with nature and I value that. The idea of agency is not to provide a solution but the tools to do something that’s actually beneficial, because each little living artwork that’s planted is supporting not only any other living artworks that are planted near it, but it’s supporting other flower patches that start to form a network across the landscape. It actually positively benefits pollinators and plants and it positively benefits the humans engaging with it because you spend time valuing the natural world and the process.

And how does agency change in works like Resurrecting the Sublime?

In Resurrecting the Sublime, you’re much more passive as an audience member. Resurrecting the Sublime is a collaboration with Christina Agapakis Creative Director of Ginkgo Bioworks and smell artist Sissel Tolaas, and my part of it was designing an emotional experience. I wanted to use the idea of the diorama, an artefact from the Enlightenment that puts nature on display in some way. But here the humans are inside the diorama: they’re sitting on the rocks smelling the lost flower while other humans are watching them. So there is an active participation in the work – you are either the observer or being observed.

But what do you do with that? I mean, there are many aspects of the work that were uncomfortable and problematic, and one of them is that we are making art about plants that don’t belong to us.

Each of those plants was made extinct by colonial forces, taking lands from indigenous peoples, and I was always concerned about my role in perpetuating that. But the idea was to actually use the language of modern science to bring attention to this issue, too.

There’s something quite cynical about Resurrecting the Sublime and in general about using biotechnologies in general – they give us the tools to create things that we are not supposed to create, to turn living systems into machines.

It’s exploiting the natural world for human benefit.

All of the works I’ve made, apart from Pollinator Pathmaker are, I would say, cynical. They’re about human values, and by human values I mean a specific group of humans and I’m probably part of that group. I obviously benefit from all of the technologies that we’re describing. I’m excited about these technologies and it’s very hard not to get excited about them, and at the same time, I fear them and I’m concerned about them because we are completely distracted.

I’m using AI to replicate the dawn chorus, not because I think that we should use AI to replicate the dawn chorus, but to bring attention to the short-sightedness of thinking that we can replicate it. There’s also that irony baked into the work of Machine Auguries.

I know this question comes up quite often, but what are the ethical and moral concerns of biotechnology that you can think of?

I don’t know how a bacteria feels about being engineered, but even thinking about life as a medium for manipulation for our own benefit is a complicated proposition. It’s probably different engineering a bacteria to engineering a human in terms of morality as far as we can perceive. But they’re part of a spectrum. Again, I’m not against biotechnology. What I’m doing is pointing out or trying to understand for myself this gray ethical area, where do we draw the line and why do we do it?

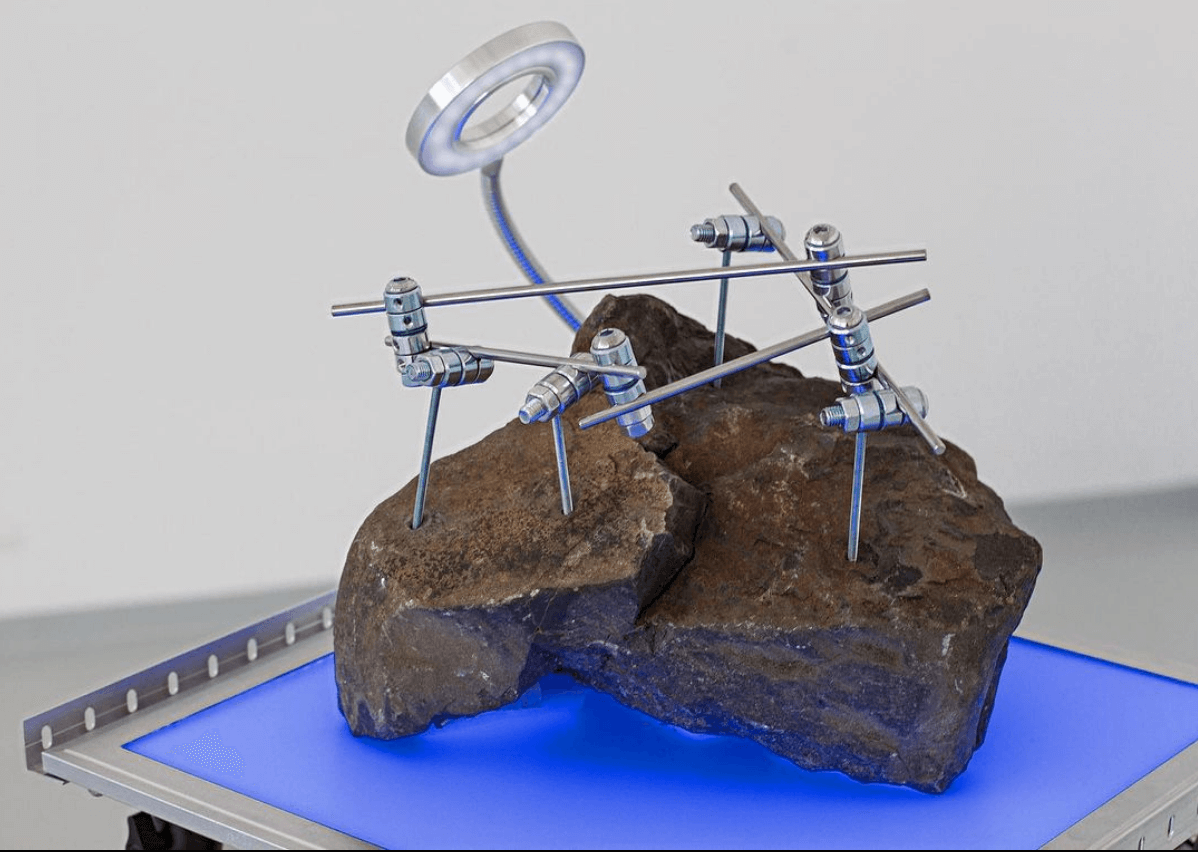

*Header image: The Substitute exhibited during the ‘Apocalypse – End Without End’ at Natural History Museum, Bern, 2022. © Nelly Rodriguez.