“If you’re doing it because you love it, then like they say, you’re never working a day in your life.”

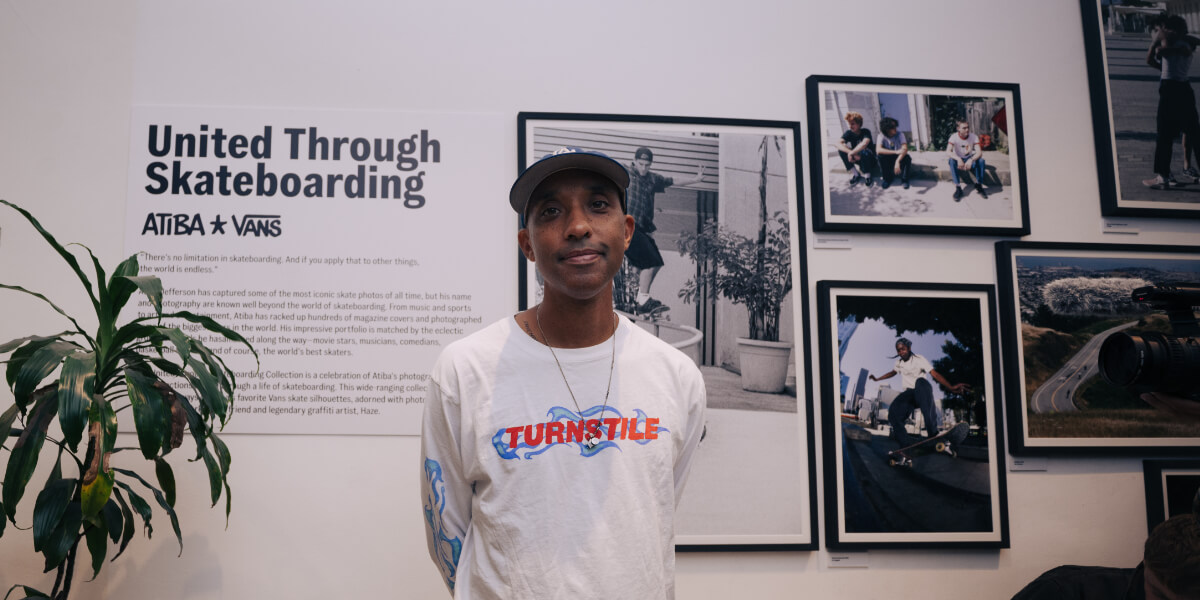

It was a crisp Fall day in Berlin. Wind blowing, grey skies, and the feeling of possible rainfall. But none of that stopped the skaters from posting up at a statue in the park that made for a perfect session. Photographer Atiba Jefferson made it out with a scarf and gloves to take a few shots of the skaters at work and hand out merch from his new Vans collaboration. With clashing concrete noises in the background and a perfect view of the makeshift rail setup, Jefferson spoke with TITLE about his passions and how they led to his inevitable destiny.

What started as a passion project changed Atiba Jefferson’s life for good. At a young age, Jefferson found his love for photography in high school. “I think one of the most impactful things for me with photography would be printing photos in a dark room. That was the magic that introduced me to wanting to take photos.”

After landing his first job at a skate shop and saving up with his twin brother to buy a shared board, he was already on a path to greatness. By simply doing what brings him joy, Jefferson became one of the most notable names in skate photography to this day. Though his focus didn’t purely stay with photographing skaters, he shot some of the biggest names and created the most memorable photos in the community.

Dating back to the 1960s, when skaters were considered “asphalt surfers”, the culture always led back to a community of like-minded people, passionate about the sport. When Jefferson decided to move to LA to pursue his passions, this same community supported him in his photography ventures.

“Community is everything, whether it’s skateboarding or not.” Atiba reflects while watching young skaters do tricks on the side of the monument. “Skateboarding, to me, has an amazing community because it’s always supported all types of walks of life, whether you’re an artist, musician, person of color, gender, everybody. It’s a really inclusive community, and that’s the way I grew up, so it fit right away.”

“Skateboarding accepts everybody.”

“It’s not perfect. I think we’re definitely seeing an amazing support toward women skaters and transgender skaters. And I think that’s been really cool. But it took a long time, especially for women skateboarders, to get the respect that they deserve from the companies and the support.”

Though the community consists of any and every personality, style, and ethnicity, not everyone may have had this experience with skate culture. When discussing his documentary Monochrome about the Black experience in skateboarding, Jefferson recalls personally having no issue, but acknowledges that there is always room to grow: “Unfortunately, racism is everywhere. But skateboarding was my escape from it. I think there are different instances. I went to South Africa right after Apartheid on a skate trip. Apartheid had only been above a couple of years before. And that was the first time.” Atiba says, taking snapshots of the skaters in front of us. “I would be a fool to say it doesn’t. I know people have stories. But for me, honestly, it was never a thing. I think the only time was really with the cops.”

Historically, run-ins with the police are common in skate culture. Using the street as your canvas for tricks and flips makes you a target for law enforcement, even though the streets are meant to be used, and that shouldn’t exclude skating. “It’s not like basketball, where that’s still your passion. But there’s a formula for how to do that. There’s training, there’s trainers. This is just like, you’re getting kicked out of a spot. You’re basically a criminal. Everyone looks down on you. You have to be really down to do this.”

The commitment it takes to learn and practice skating is something that led Atiba’s pursuit of passions to an ambitious career. Alongside commitment to the art comes the strength to pursue it continuously, even when you don’t know where it will take you. “Skateboarding, I say it a lot, is problem-solving, as we see here. To anyone else, it goes, “Why are they just flailing around and not doing anything?” and “What’s so fun about that?” But it’s an indescribable feeling to make one trick, and that work ethic is applied to anything else. It’s a very high work ethic.”

Though skateboarding showed Jefferson a side of photography that combined two of his biggest passions, it wasn’t the only path he took. From Kobe Bryant to Virgil Abloh, he shot everybody. From music to directing and community projects, he never set limitations for himself: “If you’re doing something for money, it’s going to be tricky. It’s not impossible. But if you’re doing it because you love it, then like they say, you’re never working a day in your life.”

After shooting many memorable, almost even historical, magazine covers, some of the world’s biggest names in music and sports, and working with legendary skate brands like Vans, Jefferson’s destiny became clear over time, though he never thought he’d end up here. “I think if you don’t believe in destiny, you’d be a grumpy person. I could also say this wasn’t what I was expecting. Not at all, especially at this age. But I feel very, very lucky that I’ve been able to live my life doing what I want to do. And that’s all because of skateboarding.”

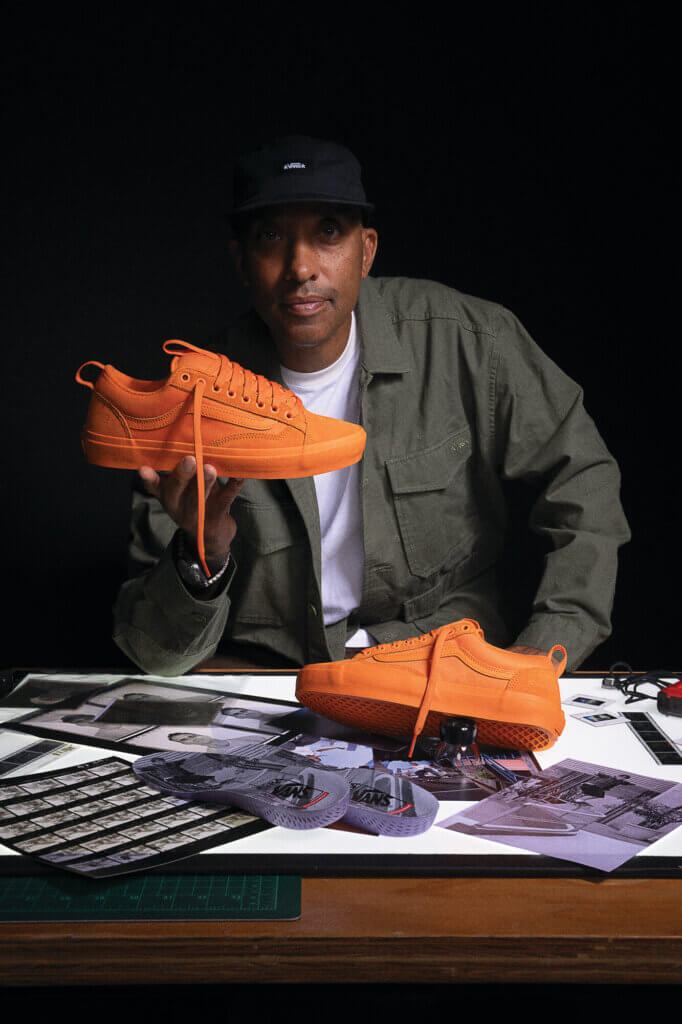

Through his most recent Vans collaboration as brand curator, Atiba Jefferson was able to cement his passions not only in print but also in material. With his images on the tags and corners of each clothing item, plastered on the packaging, and even inside the soles of the shoes, this collection carries Jefferson continuously through the culture that brought him to where he is today.