A Pure Expression of Imagination and Creativity

From the corseted bodices of the early 20th century to popular Instagram streetstyle fashion blogs, fashion continues to evolve. Fashion photography, as a medium of expression, undergoes a similar transformation.

Once considered commercially driven and less significant, fashion photography has now attained the status of museum-curated artwork. In The New York Times, Ms. Shinkle, a reader in photography at the University of Westminster, London, emphasized the growing confidence of fashion photography in explicitly commenting on the wider world. Initially hesitant to engage with politics, fashion photography has progressively become more overtly and unabashedly political since the late 1960s.

By the 1990s, “The Face,” a nonconformist British magazine challenging societal norms and ideals, introduced more thought-provoking work that paved the way for contemporary fashion photography. Figures like Collier Schorr questioned gender fluidity, desire, and the construction of identity through their images. Moreover, fashion photography not only captures the identity of the subject but also that of the artist.

Photography serves as an exploration of identity and place. Identity, in the realm of photography, represents individuality and the characteristics that set individuals apart while defining their inclusion within specific groups. This expression of identity is manifested through various means, including hairstyles, clothing, makeup, and body modifications such as paint, tattoos, scars, and piercings.

Fashion photography has produced iconic figures like Irving Penn, who revolutionized American fashion photography after World War II. Penn’s minimalist studio shots, focusing solely on the outfits, broke new ground. Meanwhile, Helmut Newton was already celebrated for his black-and-white photographs when fashion photography was still in its infancy. His deliberately sexualized images challenged gender boundaries and tackled taboo subjects such as sadomasochism and fetishism. Guy Bourdin, a painter-turned-photographer, crafted captivating narratives and compositions, defying conventional norms of beauty and morality, both in black and white and color, with a fondness for Alfred Hitchcock’s “Macguffin” technique.

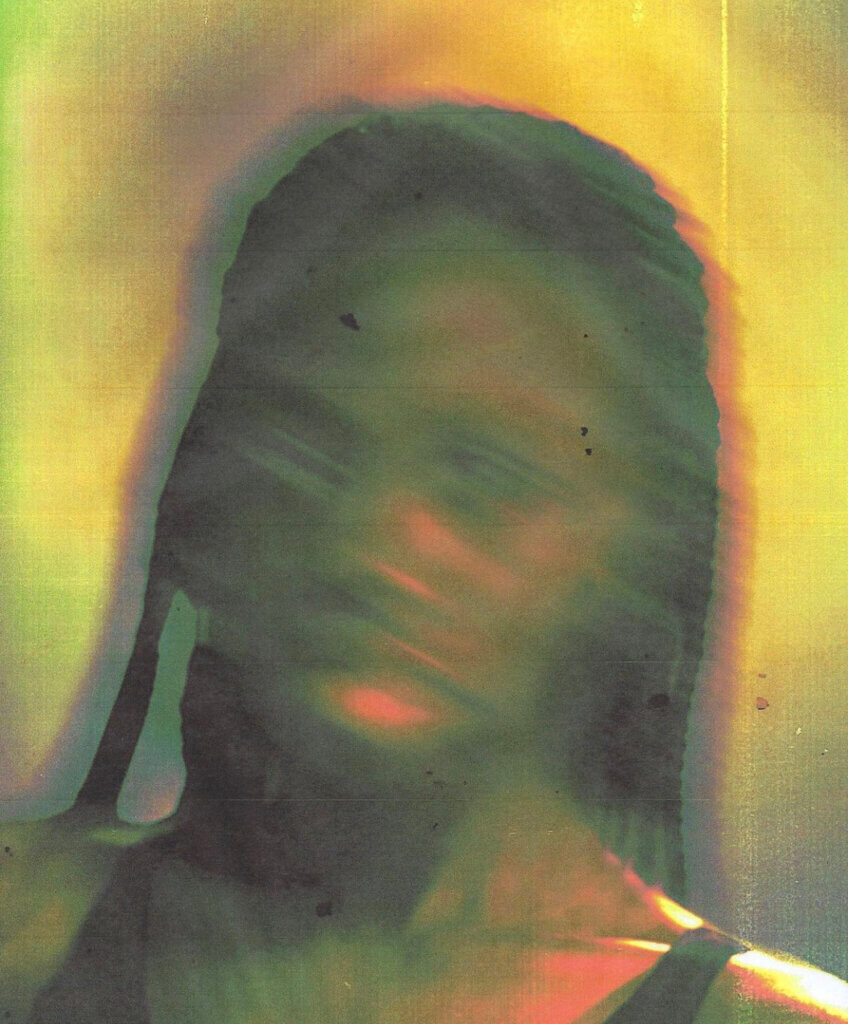

Today’s artists are paving the way for a new generation of fashion photographers who infuse their art with personal identity. Reeni (@shit.papi), a young German-based photographer, blends mixed media with surprising and bewildering accents. Her photographs resemble unexpected details inserted into surrealist paintings. Drawing inspiration from ’80s and ’90s magazines, Reeni incorporates distortion, alienation, and blurring to manipulate the body, resulting in an avant-garde approach that transforms her subjects into pure expressions of imagination and creativity.

Initially drawn to analog photography, Reeni embraced the uncertainty and limitations it offered. However, during the pandemic, she explored new techniques and began editing her images, ultimately discovering her unique style. Today’s technological advancements, evolving notions of the body, gender, and identity, provide contemporary artists and photographers with endless possibilities. The role of the photographer has undergone significant change, expanding beyond classical photography to encompass digital form, graphics, video, and other imaging techniques. The term “photographer” itself may no longer adequately describe this hybrid figure, referred to as an “image operator,” who navigates various mediums.

However, progress in today’s photography goes beyond technology and self-awareness. It addresses past issues, such as over-editing cover shoots and sexual assault allegations against prominent photographers. Reeni emphasizes that people are finally standing up against the dark side of the industry, including body shaming, cultural appropriation, racism, and various forms of abuse. A much-needed change is long overdue.