Reframing Ageing: Rosalind Fox Solomon’s ‘A Woman I Once Knew’.

In her 1970 book “La Vieillesse,” French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir analyzed how aging women are marginalized twice over in our society. They are “Other” compared to men while also being othered as older people. This analysis rings true if we look at Western art’s centuries-old disinterest in older women.

In this regard, American photographer Rosalind Fox Solomon‘s most recent work, the photo book “A Woman I Once Knew,” published by MACK, represents an exemption to this unspoken rule. In the book, Fox Solomon puts something rarely the subject of art at the center of the narrative: aging women and their bodies. The result is an intimate visual autobiography that harnesses all the storytelling power of photography and the body as its subject.

“A Woman I Once Knew” – The aging self as the subject

Born in 1930, Rosalind Fox Solomon is one of her generation’s most celebrated American portraitists. She has earned a Guggenheim Fellowship, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and Lucie Achievement in Portraiture. She has taken part in dozens of solo and group exhibitions in museums across the world, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), the Rijksmuseum, and the V&A Museum.

While many of us assume that becoming a master requires learning the craft straight out of the crib and achieving notoriety before the first grey hair pops up, Fox Solomon started her career as a photographer at thirty-eight, after she picked up the camera as a « […] a way that I just could communicate with myself. » during a work stay in Japan.

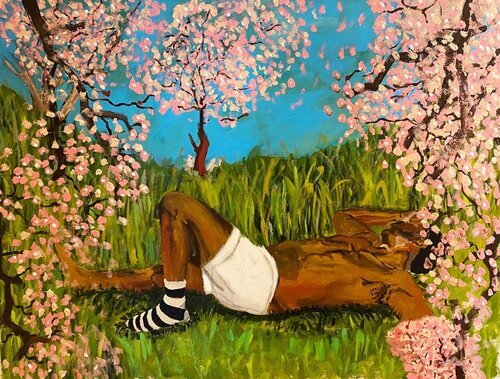

In the following five decades of her life, she documented the changes in her body with the self-estrangement that self-portraiture, especially in photography, grants artists. While Solomon Fox’s authentic, empathetic self-portraits are at the heart of “A Woman I Once Knew,” in the photo book, the artist combined the visual media she is known for with the written word in an ambitious artistic dialogue that, like the rest of the photographer’s body of work, cleverly and kindly combines the personal and the universal. The result of this choice is a sui generis, mixed media autobiography that defines artistic conventions in more ways than one.

If aging, in women and femme people in particular, is mainly painted as a descent in the obsolete and the monstrous, to be kept at bay with all one’s might, Solomon Fox portrayed an aging body as what is when boiled down to its essence—the sinewy embodiment of a lifetime. As the photographer travels the world and struggles with depressive episodes, her body is with her, morphing as her life and consciousness do.

At once mirror and companion, her body is portrayed with the honest, playful neutrality only the camera allows. While Frans Hals and Giorgione used their brushes to create constructed portraits of older women, there is little artifice in Solomon Fox’s shots but the seemingly effortless truthfulness of great art. The woman in the pictures is no allegory but a living, breathing being seen through the eyes of a woman who happens to be herself.