It’s not a secret that our society and the foundations that define our values and relations are based on patriarchy. And that is not to say that men are the perpetrators of unbalanced power dynamics or that non-male individuals are victims by default, but that our interactions between one another and the environment are deeply gendered, defined by a complex web of categories, from gender and sex to class and age. Sure, those categories and interactions are established by heterosexuality and male-informed perceptions. But how can we recognise the almost invisible way in which gender is shaping our relationship with the environment?

This is one of the questions that Dr. Catriona Sandilands posed in the episode “Ecofeminism and queer ecology” of The EcoPolitics Podcast, in which she and Dr. Sherilyn McGregor discuss how feminist and queer ecology can provide the tools to look into the intersectional axis of environmental policies, climate change, race and gender. Eco feminism and queer ecology are social and political movements that address the domination and exploitation of nature and non-men as an interlinked consequence of patriarchy. Or better, as a consequence of a dualist belief system that nullifies the pluralism of identities and forms of life — men and women, mankind and nature.

Moreso, the movement makes visible the gender norms that shape how humans experience environmental processes, and it questions the set of assumptions about what counts as legitimate knowledge and whose voice has more authority than others. In unpacking this latter point, Dr. Sandilands refer to the conversations around green policy in many countries such as the U.K., which agenda shows an obsession for green energy, making it seem shallow and simplistic as it often addresses questions such as, ‘How can we power vehicles with cleaner energy?’ when the conversation should gravitate towards acknowledging the virtual codependence between species and nature to survive.

The most evident example of how our relations are gendered is by looking at the way nature and women are objectified and seen as passive resources to be exploited for economic gain. More specifically, in the way they are seen as ‘nurturing’ — an emotional contribution that is simply taken instead of given — and in capitalist terms — a job that is unacknowledged and un(der)paid. Patriarchy, colonialism and capitalism profit from commodifying and exploiting life, and such power dynamics that perpetuate these injustices on a systematic and individual level are currently being challenged by different movements such as vegetarianism, which questions in similar ways the objectification of animals — which is not to say that eco feminists are vegetarians and vice versa.

How are these conversations taking shape?

According to Dr. Sandilands, little on queer and feminist ecology has been written in the academic world, adding that this may be because feminists focusing on this area are often deemed essentialist and simplistic for dealing mainly with the topic of gender. However, social and art movements are not only bringing this conversation to the forefront but also politicising it. For instance, the work of artists from the ‘70s, supportive of the land art and anti-gallery movements and the idea of leaving the white cube to interact with the landscape, is becoming more and more relevant. A central figure in these conversations is Ana Mendieta, who, by means of carving her body in the earth conveyed the ephemerality of the female body on earth and, likewise, portrayed the way the female body and the landscape are inflicted with violence through exploitative interventions.

Queer ecology along with other movements fighting patriarchy challenges the belief system that supports modern life as they question the very foundations of our life structures. For instance, they suggest that the way of consuming and amassing wealth inside of a family may not be the best way to think about property, family and cooperation. Instead, they unveil the opportunities behind family relationships that include not only biologically related humans.

Eco feminism has been around for at least 40 years. However, the critical theoretical frameworks it offers aren’t yet in use. But the more we question the way the gendered system grounds our experience in the world, the more we can diversify and deepen in the ways we relate with our environment, and thus propose ways to disrupt the prevailing heterosexist discourses on gender and nature.

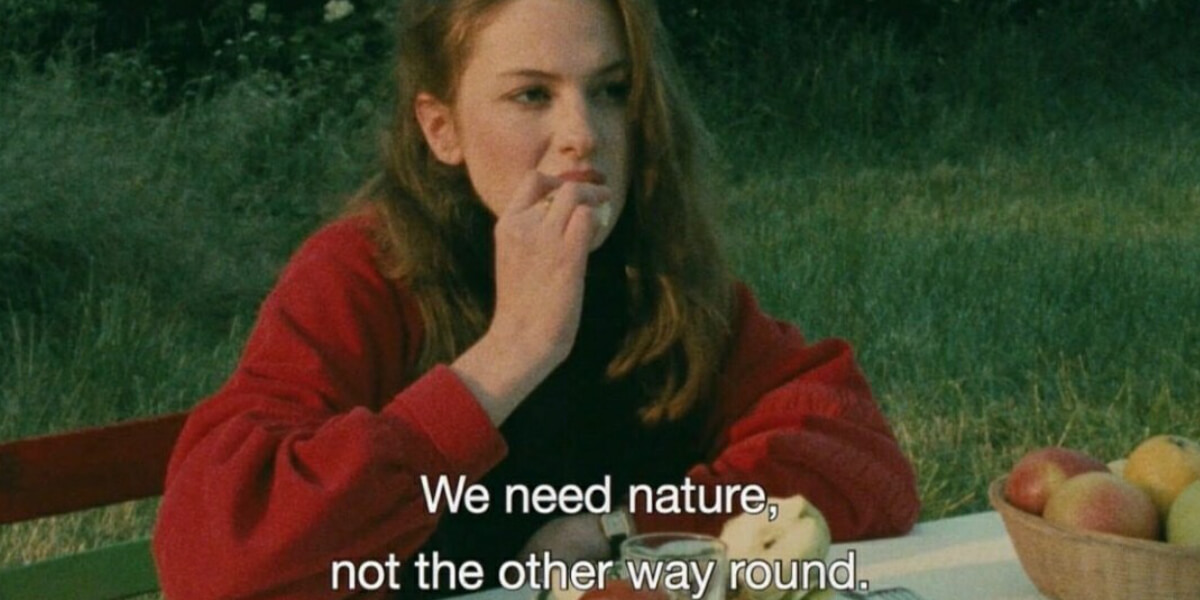

*Header image: from movie ‘For Adventures of Reinette and Mirabelle’ directed by Éric Rohmer