“We upset those who are existentially attached to the idea of love and intimacy as something you ‘can’t put a price on.’” words echoed from Rigaer94 — an anarchist squat in Friedrischain that dates back to the ‘90s — summer last year. Their faces hidden inside but a bare agenda laid out. “It was the first time that I publicly spoke about activism and sex workers in Berlin. I was very nervous. We spoke on the radio show (Kiezradio) and we introduced the philosophical ways we see ourselves.” That was the first time I witnessed my friend Blade’s activism.

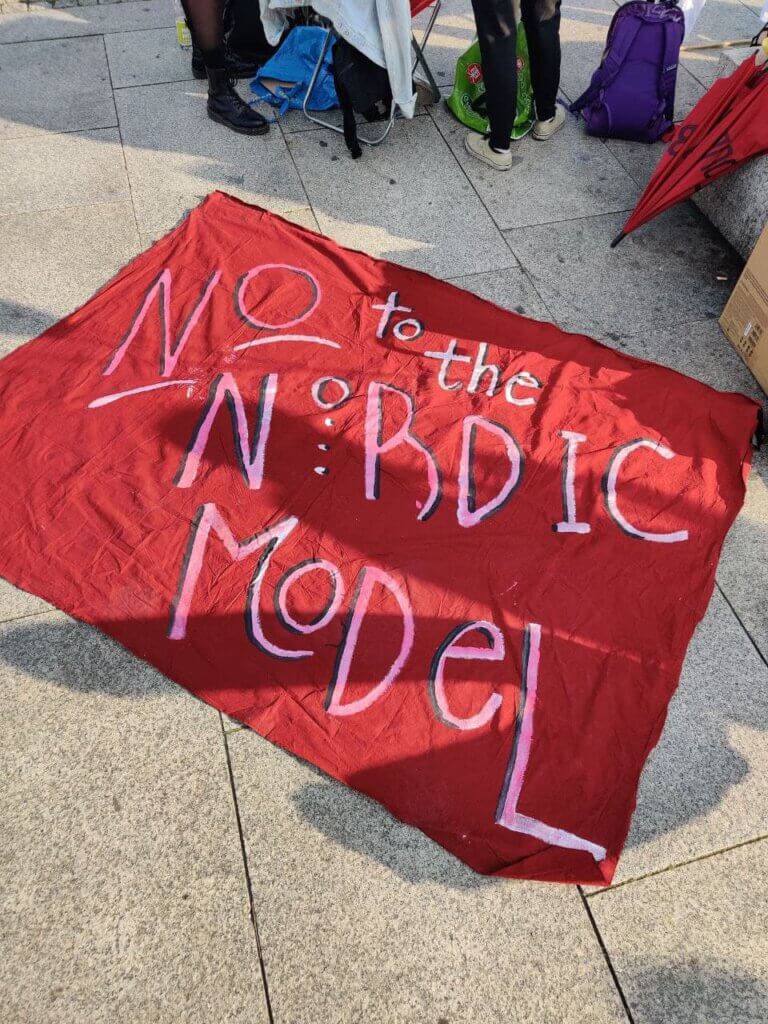

A couple of days later, the first demos intending to bring unity and visibility to the sex working community took place in the city, and a year later — this summer — a substantially bigger demo blasted “sex work is Arbeit” and “whore — power” on the streets. Furthermore, that the community’s coming forward has the main purpose of pushing to adopt the decriminalised model in Germany in 2025, besides garnering acceptance among the masses. As Blade explains, the current legal model is being reviewed, but as its name suggests, just a few can meet the criteria to work legally. “Only a very privileged minority of people with the right passports, visas and paperwork are granted a hurenpass (whore passport). But a lot of people don’t meet these high criteria, therefore the law forces the most marginalised sex workers underground to work with traffickers or with problematic bosses.”

The model came into place in 2017 in Germany, and it obliges sex workers to register at the municipality to get a hurenpass that says they’re sex workers, with a picture, legal name and address in it. But security is not the only thing at stake. By registering, sex workers agree to let the police enter their domiciles at any time if they suspect they’re selling sex at their home place. With this model, sex workers have to give up the right to privacy. But the union is voicing these challenges and explaining why a decriminalising model should be employed: because it would allow everyone to have the same rights and access to basic benefits such as welfare, sick pay and maternity leave.

But decriminalising sex work has quite some opposition for it “makes people feel that we are letting something in that they find morally or emotionally problematic. Because that is to say that it’s okay to sell intimacy,” says Blade, adding that sex workers directly challenge the ‘Cult of Love’ as love and intimacy are connected to sex, being the earlier — under capitalism — what gives life meaning and the latter what makes possible procreating human units to serve an economic system that’s supported by a dominant hetero-monogamous culture.

“We remind people of the system we live under,” by acknowledging that we are all products under capitalism, and sex workers own altogether the product and the means of production. “A lot of people don’t get intimacy or love and I think it should be right for them to pay and have professionals provide intimacy. Feminists, we know that love and sex and relationships are not untouched by capitalism. Nothing is. That’s why acknowledging that sex work is work is a fundamental feminist principle, it says: emotional labour is work and we demand the right to good working conditions,” asserts Blade.

While many sex workers do prostitution for survival, some others like Blade do it by choice, and the sex working union has become a place to support those who didn’t choose to be sex workers. The union began to consolidate when they lost their income during the lockdown in 2020 and were excluded from accessing regular state benefits. It was then when the Sex Worker Action Group Berlin (SWAG) initiated conversations with FAU — which is the union that focuses on freelancers and artists, and now sex workers, too — to demand basic workers’ rights and social security that they wouldn’t have otherwise got due to their working conditions, and in 2021 they officially became a section.

“We’ve been active for over a year. It’s a great way to demand and maintain workers’ rights and the union allows us to do this ourselves,” as opposed to having organisations speak on their behalf, which often excludes sex workers from defining what they actually need. That said, the union offers legal and community aid, by checking contracts and providing emotional support, and focuses on the legal situation on a larger scale, by campaigning for decriminalising sex workers in Germany, more specifically.

Legal and illegal — or registered and unregistered — sex workers can join the union, but when it comes to joining the demos only a few can afford to show up. “In relation to the entire community, people like me can be public because of my privilege,” says Blade, explaining that visibility puts at risk the jobs of people who aren’t legal. “That’s why we ask allies to come and join us because the demos are composed of people who can afford to show their faces and I think we have to remember that.”

Sex work intersects with many struggles: borders and migration, inequality, bodily autonomy, race, class and gender. To know more about the sex work union (FAU SW-S) visit their website or follow them on Twitter or Instagram.