Many think that the infectious energy and dynamic workouts of Jane Fonda revolutionised the realm of fitness and activewear to this day. And although Fonda propelled women’s empowerment through fitness by bringing physical activity to the mainstream, the narrative surrounding women’s fitness began to—very slowly—evolve way before, entwined with concepts of womanhood and emancipation. In fact, to look at the history of women in fitness is to look at the evolution of the female body as a source of power.

Until the beginning of the last century, societal norms dictated that women should steer clear of any form of rigorous exercise, with sweat being deemed almost taboo, an affront to femininity itself. These norms derived from the essentialist definition of women as weak, inferior and unapt—a subversive correlation to their mental faculties. And so engaging in mental or physical activities was deemed not only socially inappropriate but biologically restrictive. The female body was then by constitution a place for limitations, not a place for growth and fulfilment.

Empowerment through fitness vs. the self-fulfilling prophecy of being weak

Pointing to the self-fulfilling prophecy that women were made weak, British writer Mary Wollstonecraft argues in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), one of the earliest works of feminist thought, that women should receive rational education and be encouraged to train their bodies to become self-sufficient humans and acquire better qualities to fulfil their role in society. In this text, Wollstonecraft argues that women are taught to be beautiful and pleasing but aren’t given the tools to become fully humans as their male counterparts.

But Wollstonecraft goes a step ahead of her generation and many more to come, explaining that both men and women could benefit from frequent mental and physical exercise as a strong body and a strong mind would create a balance for health, being one of the first thinkers to address the link between the body and the mind, seen then as separate or independent from one another, and in other instances, as an obstacle to the other—only think of Oscar Wilde’s view on exercise, which epitomised the spirit of the time a century after Wollstonecraft (1895): “the only possible form of exercise is to talk, not to walk.” In fact, back in the day, lumpy flesh was considered to serve a high-functioning brain, besides being synonymous with wealth, reflected in the kings’ much larger size, while thinner bodies were associated with lower capabilities, being women expected to look fragile.

From being pleasing to becoming strong.

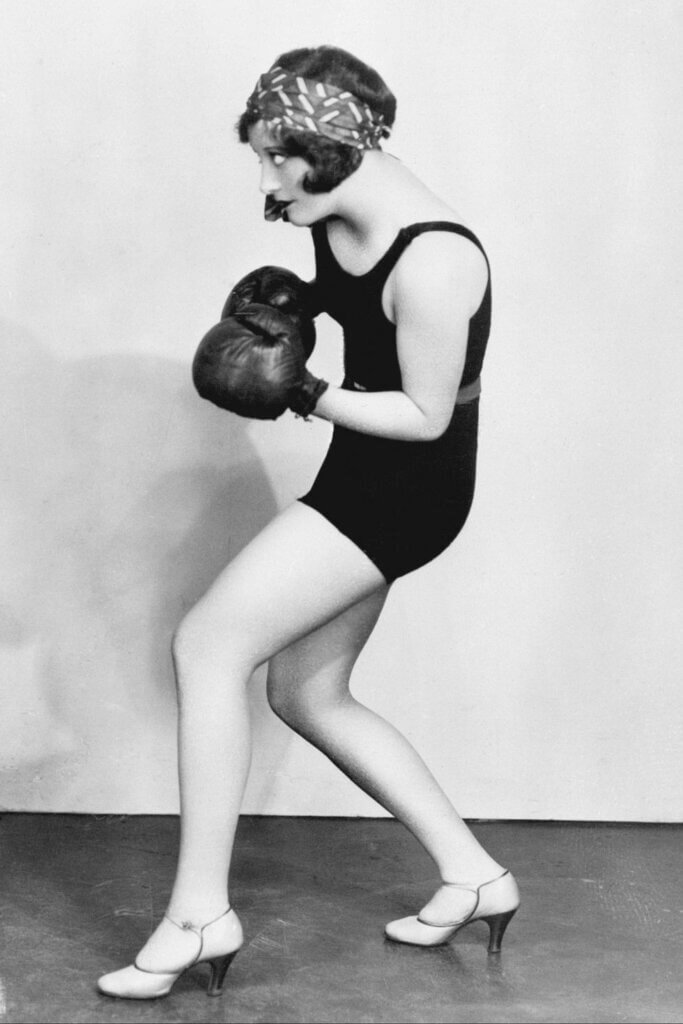

This started to change with the first female-only centres in 1920, where women joined wearing dresses, high heels, and pearls—an approach to activewear that restricted their bodies and pinned concepts onto them, or how Wollstonecraft used to say, women were subordinate to the cage that their clothes created.

In the next decades, although it praised fitness, women were still encouraged to avoid sweating in public and this saw the surge of home machines. But as activewear became more functional, sweating became more acceptable too. In the ‘50s, the ‘slimming suit’—a plastic wrap-around piece that increased the sweat rate was developed and used at the ‘reducing salons’ as they called femme-only fitness spaces.

The decades between the ‘50s and the ‘80s were coupled with radical ideas that paved the way to Jane Fonda’s success. Refuged in London, German dancer Lotte Berk invented Barre based on the idea of creating a workout that would allow women to become both strong and in touch with their sexuality. While Berk was promising dancers’ bodies and sensuality, Bonnie Prudden sold the idea of fitness as the gate to beauty. Strength and cosmetic transformation become every time more intertwined.

The attention that fitness was garnering didn’t come without backlash. These decades were tainted with rumours that exercise would turn women barren, queer, and incapable of finding a husband. By the time Fonda’s aerobic-workout videos started to sell—with Olivia Newton John’s hit Physical singing to the decade of leg warmers—becoming lean was the goal and gaining muscles wasn’t. The decade of the ‘90s saw the rise of female bodybuilders and with it the idea that women could be as strong as men.

It’s incredible to think that today fitness as much as activewear informs our everyday experience. Performance-focused products are released every day, fitness gurus offer advice to achieve all kinds of goals, and workout studios rise everywhere. Although the history of women’s fitness entwines the path towards self-confidence, emancipation, and the celebration of sexuality, unrealistic beauty standards continue to be pinned onto the female body. While fitness is becoming an unattainable concept that involves expensive memberships and performance clothes that exclude many from participating, women’s empowerment through fitness has led the way to new forms of reclaiming their own bodies through movement such as twerking, considered by many a tool of self-empowerment.

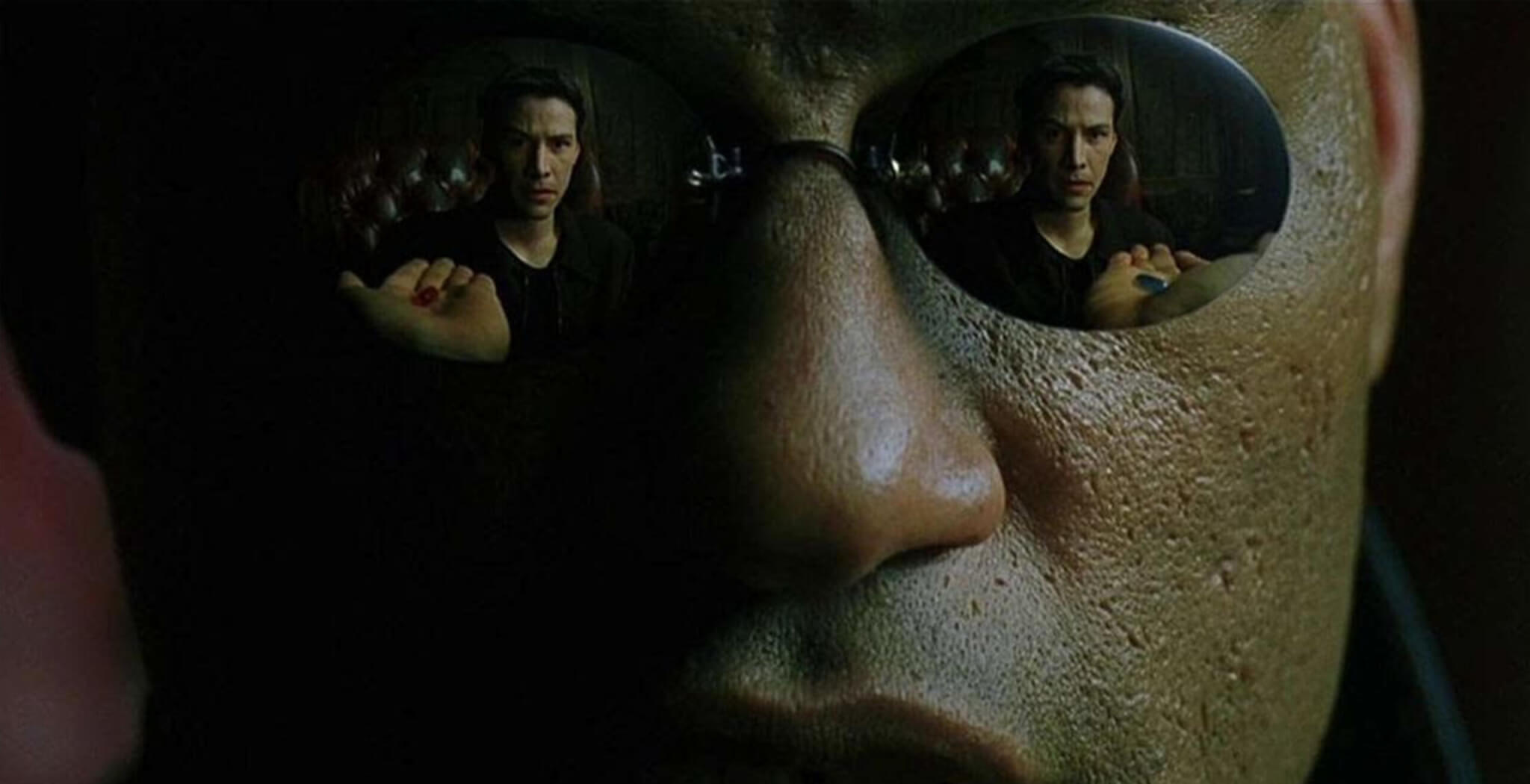

*Header: Education Image Contributor Getty via Inside Hook