From Avant-Garde to Kitsch: Tracing the Aesthetics of Change and Resistance

The concept of avant-garde is fraught with contradictions, making it difficult to define its purpose and usage. However, the term typically evokes notions of experimentation, progressiveness, innovation, and unconventional thinking, which aligns with its fundamental principles. Nevertheless, when we delve into the origins of the movement and its infiltration by consumer culture, we begin to question whether the avant-garde still exists and, if it does, what form it takes in contemporary times.

Society has long been captivated by indulgence, going beyond conventional limits, and the allure of celebrities, especially since the advent of paparazzi and social media. This fascination has been fueled by consumer culture and mass production, which gravitate toward the realm of mediocrity but with a touch of peculiarity. According to Clement Greenberg’s 1939 essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” the aesthetics of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were shaped by the contrasting forces of kitsch and avant-garde. This period marked a transition from Napoleon’s authoritative rule in France to global industrialization, characterized by a sense of pre-modernity and reinvention. As avant-garde emerged as a means of rediscovery, encouraging artists to act as agents of political change, kitsch also gained traction in subsequent years. Greenberg argues that kitsch thrived as an offering of “popular, cheap, and marketable” art formats, serving as a means to resist change.

However, can the commodification of art truly be seen as resistance or does it represent a surrender, plunging into an everlasting dream of conformity? Did a certain elite act as gatekeepers, denying the masses access to art?

Following the fall of Napoleon’s empire, Paris became the unrivaled hub of European art, as French ideals of a new society were championed by scientists, artists, and writers who challenged cultural norms and bourgeois values. By 1910, approximately 3,000 aspiring rebel artists and various art circles thrived in Paris, operating outside the established École des Beaux Arts. During the post-Napoleon and interwar periods, Paris exuded vibrancy, beauty, and intellectualism, acting as a catalyst for numerous art movements that sprouted across the globe.

But how could those outside these circles truly grasp the essence of avant-garde art? Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain,” a simple urinal, and John Cage’s compositions exploring “the absence of intended sounds” exemplify the challenges faced by those outside the avant-garde. To the discerning eye, interpretation and validity belong to the avant-garde. However, for workers and the middle class, the abstract, obscure, and complex nature of avant-garde seemed like a jumble of shapeless pieces lacking meaning.

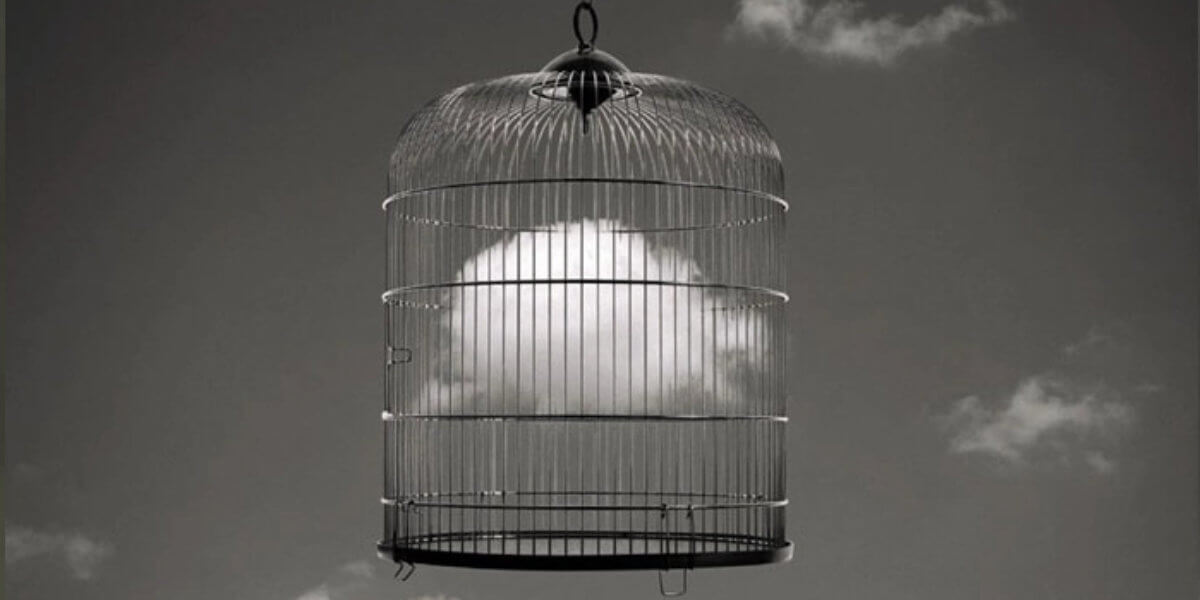

Ironically, although the avant-garde was intrinsically linked to the birth of the socialist movement, aiming to bring about radical change and embrace the spirit of “liberté, égalité, fraternité,” artistic experimentation remained the realm of the elite, who possessed leisure time to delve into the unspoken meanings embedded in these artworks. Duchamp’s “Fountain,” for instance, prompted viewers to consider a urinal as art while simultaneously challenging the conservative definition of art itself. Cage’s compositions, with their capacity to elicit unexpected reactions, narrated an unconventional tale of controlling the uncontrollable.

In contrast, kitsch allowed the masses to find beauty in emotionally and intellectually accessible imagery. Greenberg defined it as the representation of the conscious or the imitation of artistic effects, while avant-garde aimed to depict the unconscious or the process of art itself.

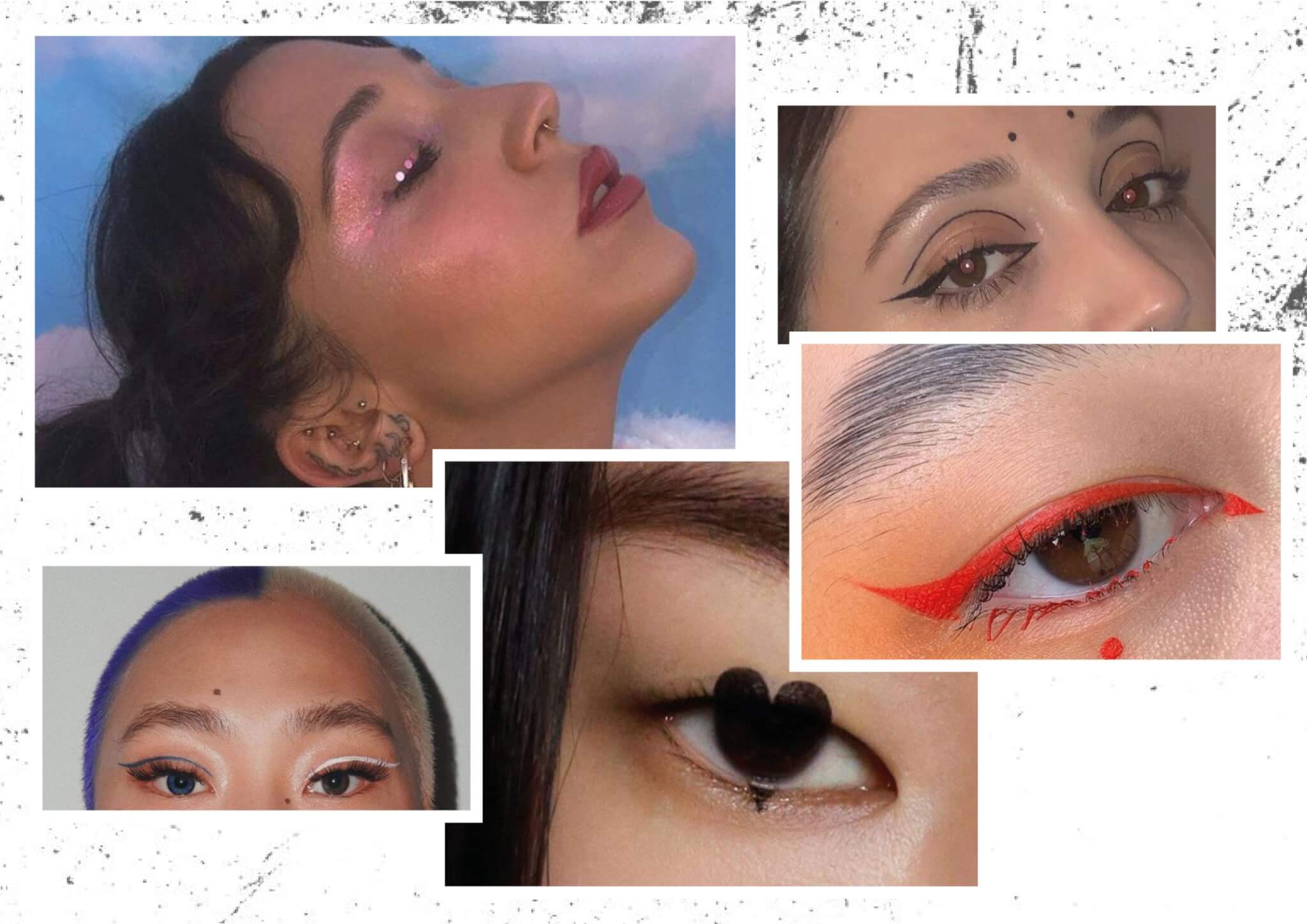

In essence, avant-garde embodies intentional beauty, whereas kitsch represents accidental beauty. This brings us back to the initial question: Is the avant-garde still truly avant-garde? The label “avant-garde” is now widely used to describe various aspects such as hairstyles, makeup, and interior design, among others, signifying edgy, daring, or unconventional aesthetics. Moreover, celebrity events and fashion shows have become epicenters of popular discussions surrounding avant-garde looks, exemplified by figures like Lady Gaga and, more recently, Doja Cat.

However, by stepping away from our obsession with celebrities and the prevailing belief that avant-garde equals excessive self-consciousness and sensationalism, we can acknowledge that avant-garde still persists and reaches a select audience. It exists independently, detached from any specific ideology, continually pushing the boundaries of artistic expression and freedom. Yet, even these innovative approaches run the risk of becoming tomorrow’s orthodoxy.

*Header image ©Chema Madoz