Imagine if we could capture with images all kinds of self-revelatory moments of encounter: ephemeral — yet clear, with great attention to the context, providing viewers details about the relation between the object, subject and the environment. An image that tells a story in the blink of an eye. An image that whispers secrets and conveys a state of boundless emotions. That and much more is what Mary Ellen Mark’s photography gracefully achieved over almost five decades, since she held a camera in her hands at the age of 9.

Looking at Mark’s photography, we are certain of two things. The first one, that the streets used to inform the aesthetics of magazines, and the second, that Mary Ellen Mark was born in the heyday of the women’s rights movements in the U.S. and so her subjects are mostly women of all ages, living on the fringes of society: sex workers, orphanages, refugees, homeless, mentally ill, and many more.

Between 1963 and 2015, Mark captured intimate, provocative stories of characters she spent time with for weeks or months, not only documenting their lives but also engaging deeply with their subjects and remaining in touch with them. One of the stories that illustrates the most Mark’s long-standing personal relations to the people she documented is the famous documentary series about “Tiny,” a 13-year-old girl Mark met surviving on the streets of Seattle in the early ‘80s, exposed to the various deals happening on the streets. Mark continued to document Tiny and her ten children until Mark’s passing in 2015.

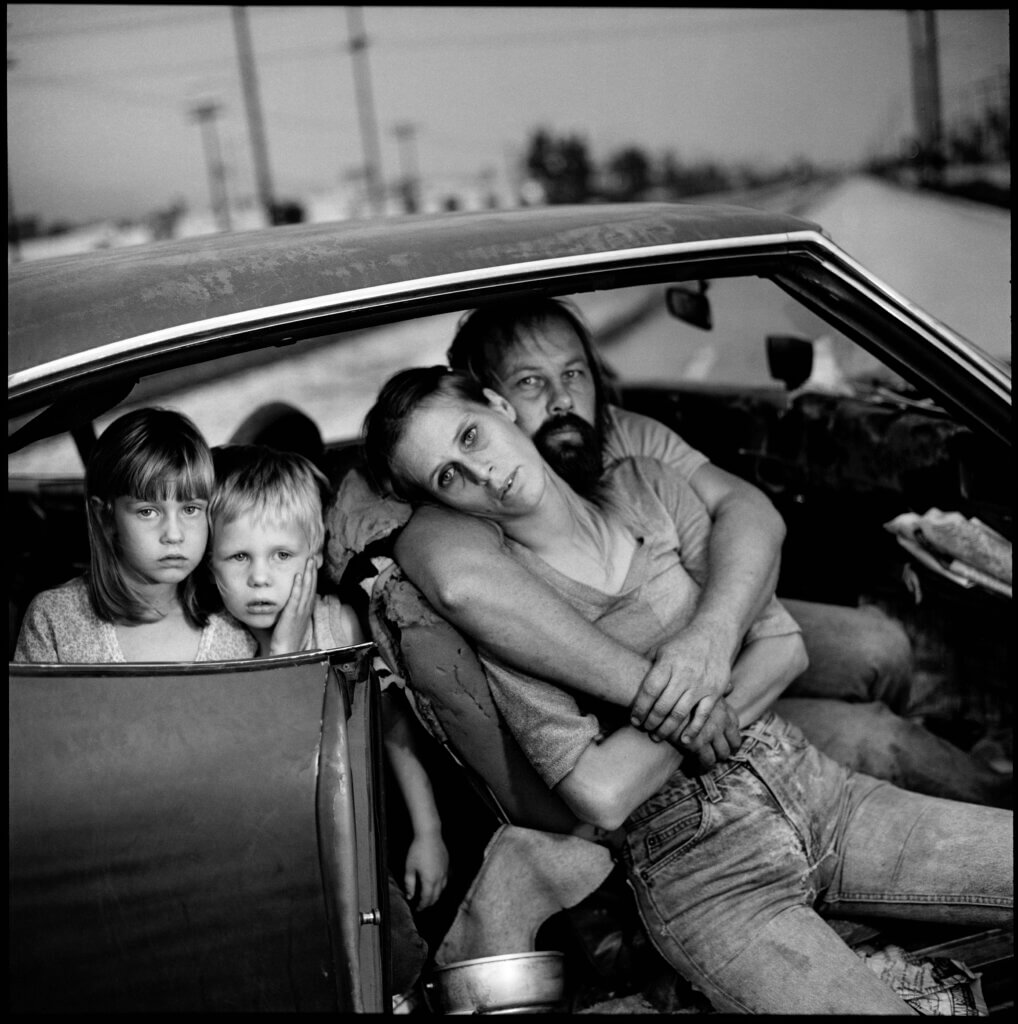

Or The Damm family in their car, commissioned by Peter Howe from Life magazine, in which she photographed a homeless family in 1987, who she visited once again in 1994, only to find their conditions were ever-so more detrimental, “squatting in a dilapidated, deserted ranch house,” as Mark recalls.

Mark’s photographs are not only imbued with personal relations and intimate stories, but they’re imbued with humanist ideals for they portray what the zeitgeist doesn’t portray: those in need or excluded from society. Her black and white photographs, no matter their lack of colour and boundless complexity, conjure some inexplicable joie de vivre. Perhaps that is because of the sympathy she’s able to transmit, a kind of immediacy and abstraction — as she used to say to explain why the preference for black and white photographs — devoid of urgency and gore, or as The New York Times Magazine referred to her work in the late ‘80s, “sad, but not damning.”

There’s a shift, however, in her approach to photography when she visits India, and we see that most of the photographs taken there are in colour, capturing the way women used colours to grace themselves, as Mark explains. The first time that Mark visited India was in 1968 and then again in 1980 and 1981. During these journeys, she documented the sex workers from Bombay and a traveling circus in Kerala. As a woman traveling alone, Mark was a subject of abuse or distrust, but her status as an unmarried woman granted her a spot within the sex workers community. Mark recalls the moment the madam of the brothel saw in her sisterhood, saying that Mark, like them, was a lonely woman and therefore one of them.

Mark’s extensive body of work, one of many extremes and nuances, of infinite stories and places, has been collected after her passing by Mark’s husband and collaborator, film director Martin Bell, in a book that he’s assertively titled The Book of Everything: 600 photographs spanning brilliance, intimacy and sympathy in documentary photography, which is nowadays exhibited in Encounters, the first major retrospective of the photographer’s work at the photography space C/O in Berlin until January, 2024.

*All images courtesy of The Mary Ellen Mark Foundation via C/O Berlin