The lighthearted, eccentric way of looking at and portraying life experiences in film has made Agnès Varda an acclaimed filmmaker whose influence is yet to be grasped. Although she never endorsed being called a feminist, “I didn’t see myself as a woman doing film but as a radical filmmaker who was a woman. Slightly different,” she is one of the first women behind the camera to gain prominence in a male dominant industry, hostile to beginners, without ever changing or accommodating the way she wanted and did film. “The films are remembered. And this is my aim — to be loved as a filmmaker because I want to share emotions, to share the pleasure of being a filmmaker,” she told the New York Times in 2009.

One of the aspects that will make Varda’s films forever remembered is the way she shifted from an objectifying to a subjective gaze and with this, she has — perhaps unintentionally — unveiled the correlation between urban spaces, objectification and idealisation of women, on whom expectations and frustrations are constantly projected and unconsciously validated. Varda’s lens has challenged the portrayal of beauty as seen by men, and enacted ways of being attentive to the presence of everyone and everything in front of the camera.

In Varda’s films, vulnerable characters are desiring subjects as opposed to objects of desire. In Cleo from 5 – 7, her second film seven years apart from her debut film La Pointe Courte (1954), a pop singer awaits for her cancer results. As the name suggests, Varda follows Cleo in those two hours which is when Frenchmen used to meet their mistresses after working hours. Cleo is a beautiful and talented woman often seen and reduced to those categories — a looked-at subject. Mirrors reflecting different angles of her throughout the film, including a broken mirror distorting the image of her, informs Cleo’s own perception based on how others see her. Towards the end, Cleo becomes the looking subject as fragments of her disappear: she becomes whole, detached from objectification.

Characters and surroundings are equally important in Varda’s films, each of them imbued with their own anxieties and desires. Is in these surroundings that overlooked people and ideas are generally stripped away from their agency and assigned to social and political narratives. In Sans toit ni loi (1986), also known as Vagabond, the story of a young, female drifter refuses to follow traditional life structures — where doing domestic work, bearing children or having a fixed place to stay aren’t optional but mandatory life duties — and decides to wander through a cold country until she’s found freezing to death.

The main character, played by Sandrine Bonnaire, is an unaccommodated woman whose surroundings expose her to poverty, sexual violence, aggression and abandonment, offering a more realistic, less romanticised narrative of female emancipation. “You chose total freedom but you got total loneliness,” says to her a male farmer who finds her smoking cigarettes instead of doing the chores he asked for in exchange of shelter. The film depicts how urban spaces and modern life are sewn into patriarchy, the complexity of emancipatory trajectories and Varda’s empathy in portraying these narratives.

The plethora of visual works Varda created for over seven decades is marked by her education in photography. Varda’s exquisite attention to framing is remarkable throughout her body of work, as seen in La Pointe Courte — a film that inspired Hiroshima Mon Amour (1961) and the laid the foundation for the French New Wave — a film movement characterised by fast-paced editing, inexperienced cast and close-ups of faces, often dealing with class struggle, youth culture and sexuality. The movement, ultimately, emphasised the director’s artistic vision over commercial products, a thought in line with Varda’s “cinécriture,” a term she coined to refer to “handmade cinema.”

Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse (2000) and Les plages d’Agnès (2008) are great examples of cinécriture. The former presents “subjective documents” — termed by her, too — a form of documentary that blurs the line between art and life. The latter, Les plages d’Agnès, is an autobiographical essay where Varda revisits places that are important to her, including the time she spent next to Jacques Demy, her husband — also a member of the French New Way — who she once followed to Los Angeles, where she met Andy Warhol and was featured in the first-ever printed cover of Warhol’s magazine Interview. “To love cinema is to love Jacques Demy, painting, family and persons. And again, to love Jacques Demy for a long time, until the end,” says Varda in the film, which compiles interviews and footage that they made during their time together.

Varda’s unconventional film style tiptoeing the line between documentary and fiction was epitomised in her last masterpiece, Varda by Agnès, which premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2019, only a few weeks before her passing at the age of 90. In this film, clips from all her works are collected and they document her playful subjective gaze and her artistic aptitudes to shift from analog to digital filmmaking. Although her talent didn’t get as much recognition as male filmmakers did — many of whom she advised, her work has been praised in the last years and it has earned her the honorary Palme d’Or at the Festival de Cannes in 2015 and the honorary Oscar at the Academy Award in 2017, becoming the first female director to receive the latter award.

The work of the Belgian-born photographer, who wrote a script and directed a marvellous film with no prior technical knowledge at the age of 25, will be remembered at the cultural centre silent green in Berlin. Photographs, films and cross-media installations will be on display from June 9th. Varda’s unique body of work makes it clear that she didn’t make films that no woman has ever made but that no one has ever made, as she stated several times, resisting the term ‘female director.’

For more about her work, visit Varda’s production company Ciné-Tamaris.

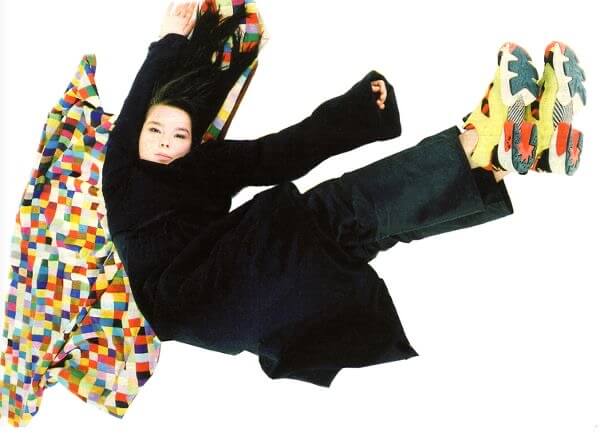

Head image: Agnès Varda by Julia Fabry ©Ciné-Tamaris