GEOMETRIC ROOMS – JULIAN BAECHLE

A system that can grow and adapt. Or shrink itself like shrews in winter. From inhabiting a sidewalk to a sounded landscape with Virgil Abloh and Lucy Styles. I lived with Julian Bächle in a shared flat in 2013 – when he was studying at AA School of Architecture in London. The apartment had irregular sloping walls and blue carpets – but Julian’s room was different. Wherever he went he took his time to find simplicity. Entering his room my eyes outlined the few objects that he owned. The walls wore three black and white photographs. A trumpet of plaster was resting on his desk. During Winter he brought a human-sized sculpture up to our roof. It was a dome-shaped body, looking out to the city like an open frame sphere. Today he is integrating urban agriculture into buildings with minimalism in his bones.

How can architecture influence the way we move through space?

Architects program space.

What was the first thing you constructed?

A physical model demonstrating an avalanche. Back in primary school when we were asked to hold a presentation about a climate-related subject. My friend Marc and I were always skiing together and we wanted to explore how to prevent a snow slide. So we built a model out of paper-mâché. A one-meter high paper mountain on an MDF board. We tested various objects to prevent the snow masses from spilling into the inhabited valley. Our results were presented in class and demonstrated live. The conclusion was to keep or plant many trees to stop the snow

Since when are you an architect?

My first project started with an object. I found a used trumpet in Bricklane, London. I studied the shape of the horn through technical drawing, 1:1 plaster casts, and paper models. Later, I tried to play the trumpet. The three tones coming out of it, I translated into color. The final piece shows an inhabitable horn in red and blue. The idea of sound has its own colors.

The human brain reportedly prefers buildings with curving, how does yours behave?

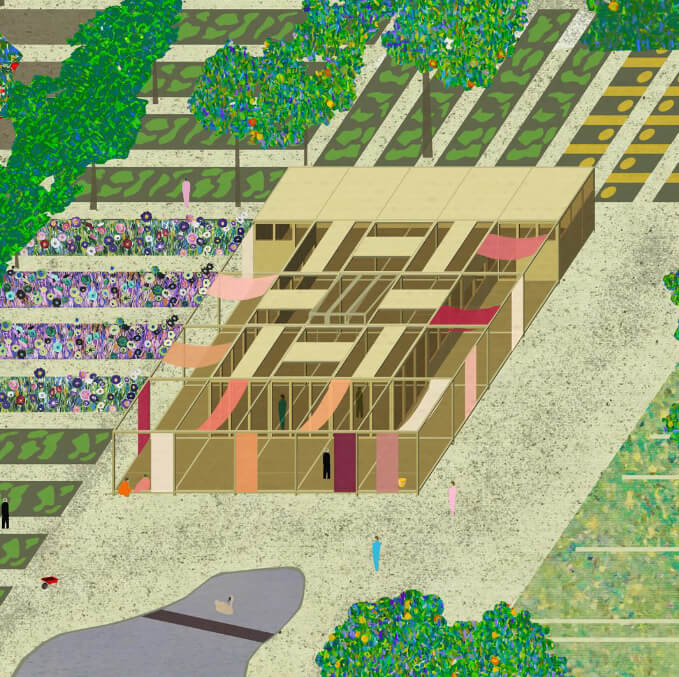

My brain likes geometric forms. The circle, the square, and the rectangle. When I design, a shape is never the driving factor. Instead of a result of a long process considering context, needs, materials, and regulations. I design through mapping out sketches. Exploring the relationship between mass and emptiness, private and public space, temporary and permanent use. Models let me understand the space in relation to its context. So architecture can integrate into its immediate surroundings while being autonomous.

In what space did architecture begin for you?

Until I was 8 years old, my parents used to have their architecture studio in our living room. All our holidays were planned around studying architecture, art, and design. Visiting the Teshima Art Museum by Ryūe Nishizawa. Looking like a white chamber with a fragile shell. Standing inside an aperture room. Or traveling to the desert laboratory “Taliesin West” by Frank Lloyd Wright. Every year, we still travel to Soglio in Switzerland – mountains and a historic village that never changes. A silence where I can think. We have to start with the existing and transform it into something new. I understand architecture as a collective project towards equality, sufficiency, and subsistence.

How can architecture have a positive impact on the environment?

The orientation of a building can lower its energy usage while adapting to the environment. Choosing the material is just as crucial as the construction and disposal of materials. More wood and clay buildings are being constructed in Germany which is more desirable compared to concrete and steel. I can see an increase in recycled materials as we are learning more about natural systems. With buildings in the future that generate more energy than they require.

There will be more people in cities, how could new homes be built efficiently?

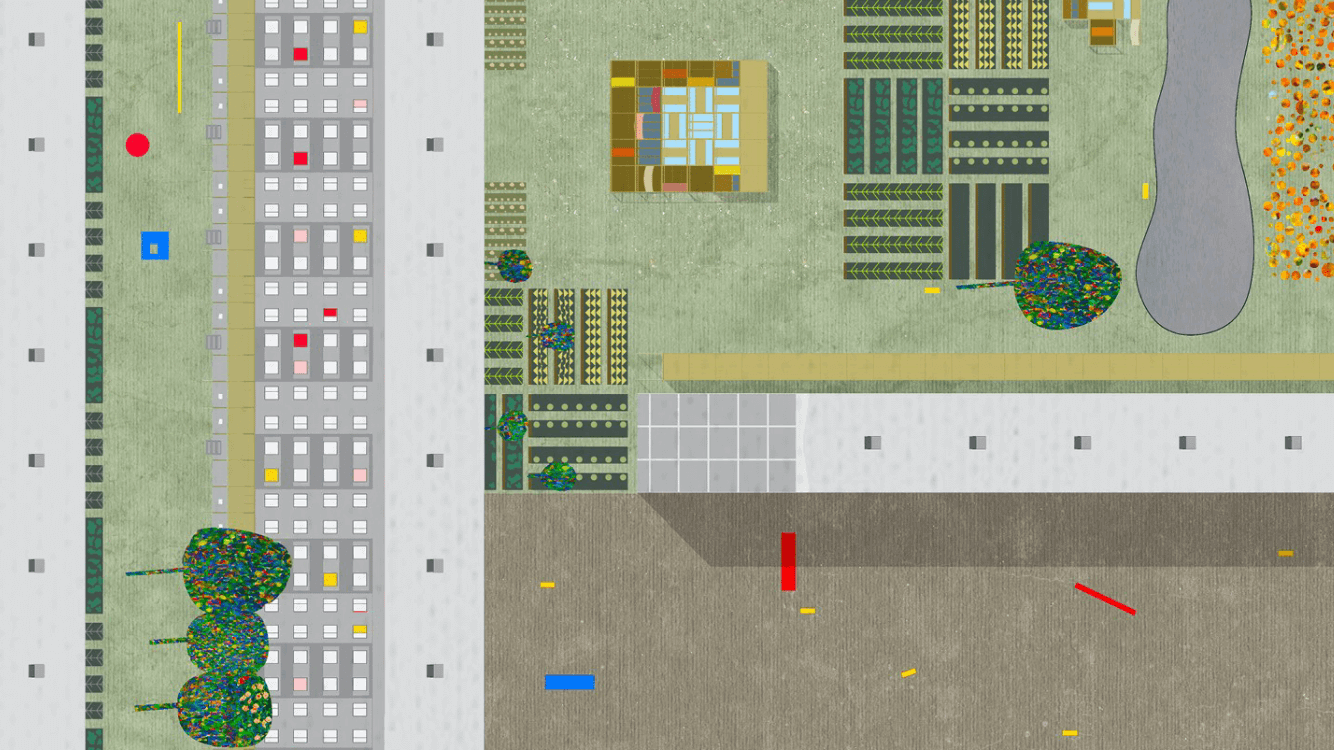

The lack of living space is a major challenge in most cities. 17% of the total area in London is pavement. My project “Inside Out Knightsbridge” makes the sidewalk habitable. With a new zoning plan reconfiguring the city on an urban scale. A 400m historical facade is preserved as a mask integrated in-between the new building fabric. Questioning the indoor and outdoor and proposing alternative forms of living.

How will humans live together in 100 years?

We will live carbon-neutral or even climate positive by 2121. The consequences of our impacts will require decentralization. Short distances to prevent unnecessary travel. Hyperlocal life in a global world. With self-sufficient neighborhoods. We will build with biodegradable materials, reuse and transform existing buildings. A community of around 200-400 people. Producing energy as a resilient unit. Where everyone recognizes each other while still allowing to be anonymous. A counter-proposal to the family as a new basis of society.