Benjamin Li’s Exhibition at FOAM Digs into the Chinese-Indonesian and Colonialism through Food

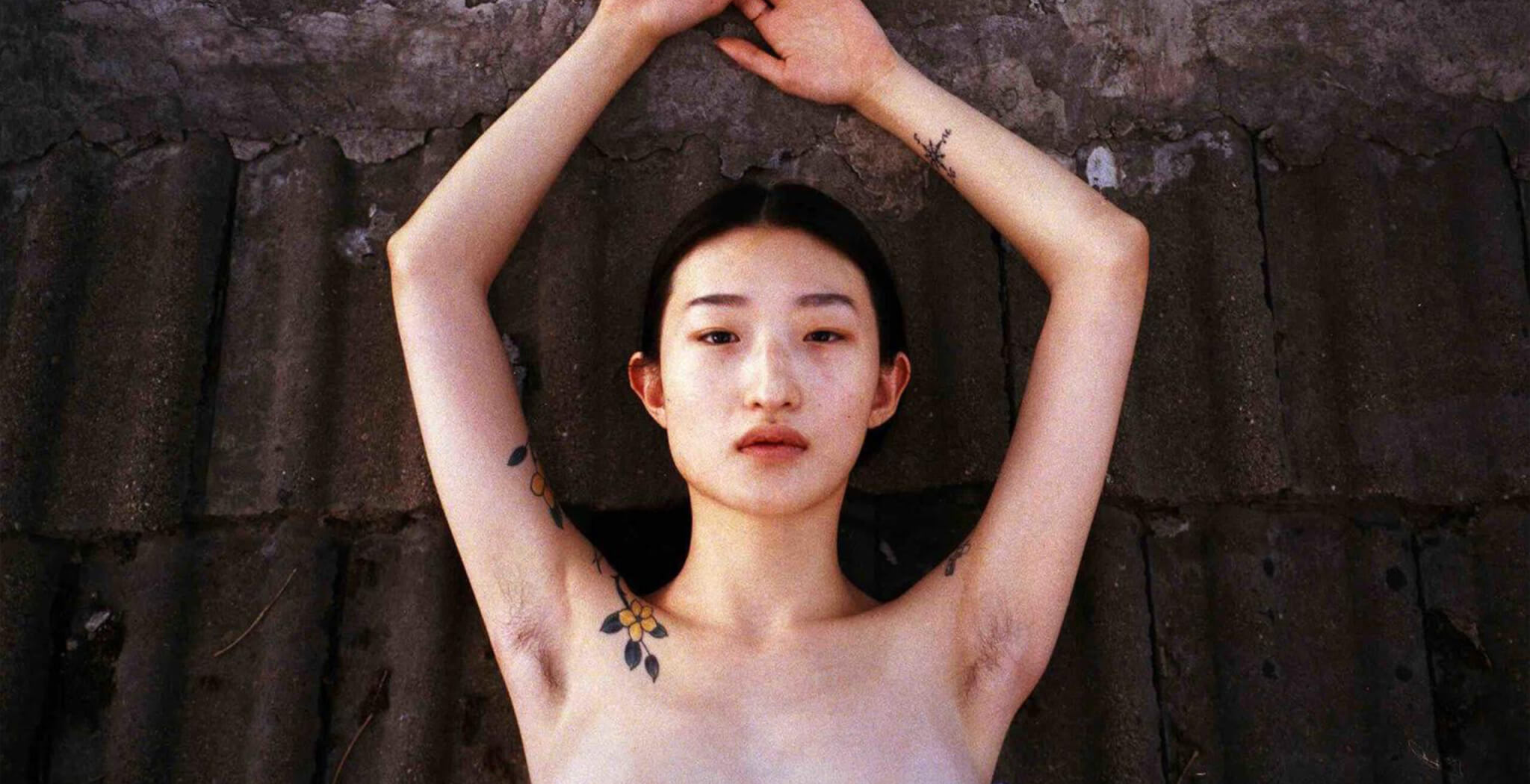

Visual artist Benjamin Li examines issues of cultural heritage, identity, and the enduring effects of colonialism through the lens of food. Raised between Chinese and Dutch cultures, the Rotterdam-based artist delves into the complexities of migrant experiences, with Chinese-Indonesian restaurants playing a central role — a symbol of colonialism, community, and identity.

His current exhibition at FOAM, In Search of Perfect Orange (until 01.12.2024), reflects on the intersection of identity and heritage through a series of images, video installations, and objects that evoke the atmosphere of a traditional Chinese restaurant. By documenting food and showcasing items from Chinese-Indonesian restaurants, Benjamin’s work digs into the historical ties between these establishments and the Netherlands’ colonial past in the East Indies.

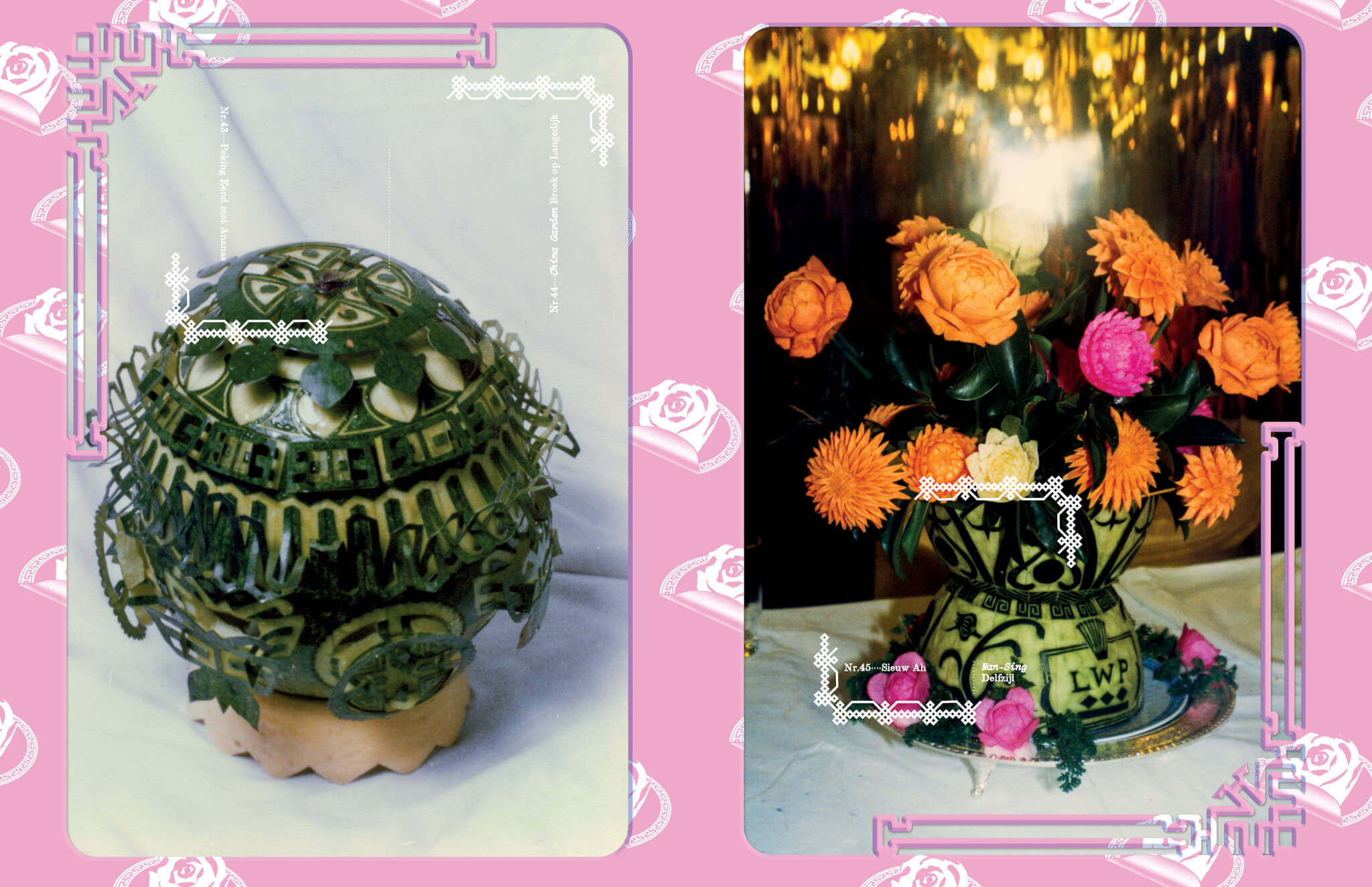

Carved flowers made of carrots, family-owned businesses, and a new genre of food heritage come together in Benjamin’s work.

Hi Benjamin, it’s really exciting to talk with you! How would you introduce yourself and your work?

Born to Chinese parents who migrated to the Netherlands seeking a better future, but raised for the first 12 years of my life by a Dutch foster mother, I am an artist who moves between cultures. With a background in psychology, I studied Photography at the Willem de Kooning Academie and completed a Master’s in Media Design at the Piet Zwart Institute, both in Rotterdam. This year, I finished my residency at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, a two-year programme for artists to develop and deepen their practice.

What are the topics you explore through photography?

Although I studied photography, I don’t see myself solely as a photographer focused on the medium. I consider myself a conceptual artist who uses different media and techniques to express my ideas. In my work, I explore topics related to identity, representation, displacement, foodways, and a sense of home. With a personal perspective, I aim to address local and global issues often experienced by people with a migrant background. For me, working with these topics connects me to my family, heritage, and history, while also allowing me to connect with others who share similar experiences.

Would you say the exploration of heritage through the lens of food has eased the personal conflict of feeling both foreign and local in your surroundings?

For me, food is much more than sustenance. Eating and working with food means connecting with its history, culture, customs, and behaviours, to name a few. The act of consuming food is also often part of social interaction, fostering exchange and mutual affection. For me, food is a vehicle for connection — with oneself, with others, with a culture, and with history. Working with food provides insights on personal, local, and global levels.

In Search of Perfect Orange, currently exhibited at FOAM Amsterdam, you explore themes of identity and cultural heritage through documenting food. Can you tell us more about how your work as a photographer and visual artist reflects these themes in this exhibition?

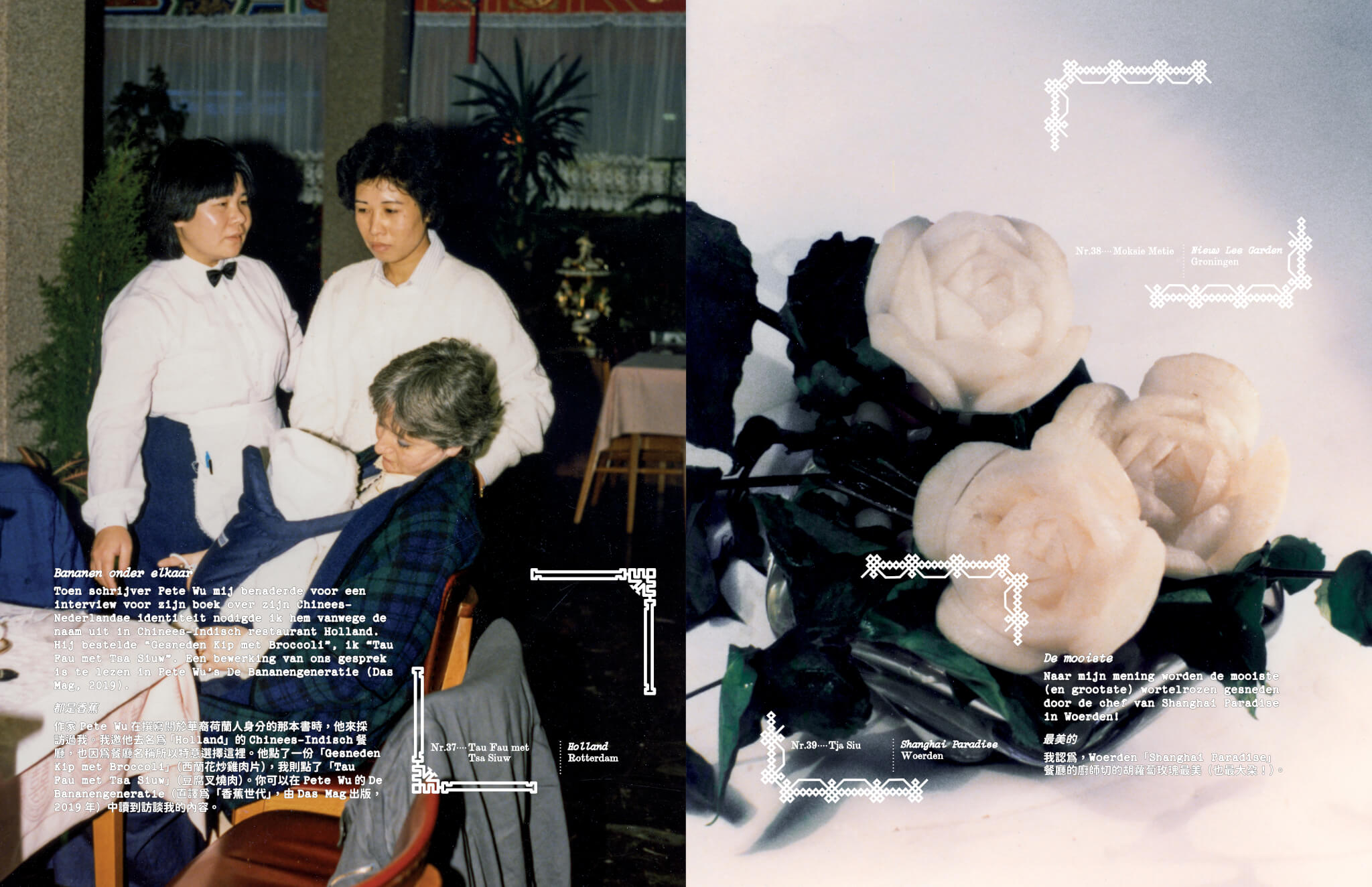

This year, I self-published my book, Chinees-Indisch Restaurant Stickeralbum. The pages consist of family archive photos showing my family’s former restaurants and intricately carved flowers and figures (often made from carrots), which are used for special occasions or to decorate dishes. The book includes spaces to affix stickers of Chinese dishes I’ve photographed over the years. I also wrote an essay explaining my background, the project, the origins and history of Chinese-Indonesian restaurants, and events that have affected the Chinese community, such as stigmatising comments by Gordon Heuckeroth from Holland’s Got Talent and the Covid-19 pandemic, during which we were victims of blame.

At FOAM, we enlarged several pages of the book and displayed them on the walls. We also framed and placed enlarged versions of the stickers on top of the prints. There’s a video work showing my father carving a rose out of a carrot. Additionally, I present my version of the board game Halma (commonly known as ‘Chinese Checkers,’ even though it has nothing to do with China and is actually of German origin). During my residency at the Rijksakademie, I created a large-scale version of Halma called In Search of Perfect Orange. My version has a diameter of 1.30 metres, with pawns made of epoxy copies of carrot roses carved by my father. The game is displayed on a large rotating round table, with stools around it for people to sit and observe closely. I also decorated the windows with ornaments commonly found in Chinese restaurants. Through this exhibition, I aim to evoke the atmosphere of entering a Chinese restaurant for the visitors.

You’ve been collecting written memories, photos, and menus from more than 1,000 Chinese-Indonesian restaurants in the Netherlands, the basis for many of your works and series. What inspired you to start this archive?

In my work, I explore Chinese-Indonesian restaurants by photographing unique dishes and collecting takeaway menus. I began this project in 2014, and over time, it has expanded to include postcards, sugar bags, and ceramic objects, all related to Chinese restaurants. My reasons for starting this archive are threefold: 1) Nearly all my family members have worked in or owned a Chinese-Indonesian restaurant at some point; 2) the Chinese community and these restaurants have often been victims of microaggressions and stigmatisation. A significant incident in 2013 shaped my perspective: During Holland’s Got Talent, a Dutch jury member, Gordon Heuckeroth, asked a Chinese contestant if he was going to sing “Number 39 with Rice,” which I believe was both wrong and stigmatising, revealing how Chinese — and Asian — people are often perceived; 3) The history of Chinese-Indonesian restaurants is tied to Dutch colonial history and is fascinating, especially as their numbers decline today.

Out of all the projects the archive has inspired, which one feels the most personal or cathartic to you?

On a personal level, my video work In Search of Perfect Orange (2017) is particularly dear to me. It shows food being passed from one plate to my parents’ hands and then to another plate, continuing until all the food has been transferred. While making the video, I watched my parents try to hold their hands still to form a bowl to receive the food, creating a powerful and vulnerable image. The stillness and emotion in that room were unlike anything I’d felt before in my other works.

On another level, my recent publication Chinees-Indisch Restaurant Stickeralbum is especially meaningful to me. Not only does it reflect my journey and thoughts, but it also speaks to a broader narrative. By engaging readers to place stickers of dishes in the book, I hope to spark curiosity about the food and encourage them to reflect on their experiences with Chinese restaurants. I also hope the accompanying essay stirs a conversation about the Chinese-Indonesian restaurant and Chinese community in a more positive light.

What can your work tell us about the colonial history of the Netherlands and the so-called East Indies?

The Chinese-Indonesian restaurant is a direct product of Dutch colonial history. Nowhere else in the world does this specific type of restaurant exist. When Indonesia gained independence in 1945, many people from the East Indies moved to the Netherlands, bringing with them new flavours and seeking familiar ones. It was during this period that Chinese-Indonesian restaurants began to emerge, blending Chinese and Indonesian flavours and adapting them to Dutch tastes.

What are your thoughts on the Chinese-Indonesian food scene in the Netherlands?

I think it’s amazing that these restaurants exist. To me, the Chinese-Indonesian restaurant represents a kitchen of survival. The food had to adapt to Dutch tastes, and these restaurants became a way for migrants to earn a living. Many Chinese people in the Netherlands have worked in or have some connection to these restaurants. Beyond serving food, these restaurants also play a social role — people often come in to chat about their lives.

Would you say you’re a foodie?

No, I’m not sure what a foodie is exactly, or at least the image I have of a foodie doesn’t appeal to me. But I do enjoy eating and trying new things. I’m always happy to taste something new, something that surprises me, or something I haven’t experienced in years.

What dish evokes both alienation and belonging for you?

Chinese tomato soup. I think that speaks for itself.

What’s coming up next for you?

I’m currently working on several exhibitions that will take place next year. I’m also looking forward to resuming my travels to visit Chinese-Indonesian restaurants, as I still have a few left to see. I’m really excited to taste their food and continue my project.