We all love a good niche genre. In music in particular, these specific genres are often characterised by a relatively small but dedicated fan base and a unique sound aesthetic, themes or production methods.

And suddenly the sound of the underground arrives in the guise of pop, of all things. The songs are short and fast, the bass is distorted and the voices are so high that the singers sound like cartoon characters. At the same time, the choruses are often catchy in the best pop style. Introducing: Hyperpop.

The genre is something of a caricature of pop music. It plays with bits and pieces from the musical trends of the millennium, from Britney Spears to rave music to nu metal. Anything goes, as long as it sounds as eclectic as possible. To call it a genre is somewhat a misnomer, as it’s really every single genre at once. Whereas the 90’s “grunge” could be characterized by detuned guitars and dissociated vocals, or the 2010’s trap/rap/hip-hop and EDM are myopically fixated on ridiculous amounts of near-subsonic bass and not-o-tuned vocals, Hyperpop has no discernible “thing” beyond being… well… hyper.

Originally characterised by its glossy, high fidelity sounds and sugary vocals, a new generation of artists have evolved it with shorter, rowdier hooks laced over raw and blownout 808s. Charli XCX, together with pioneering star SOPHIE and PC Music founder A.G Cook, helped kick off a global phenomenon of experimental, maximalist pop

It was 100 Geks track ‘Money Machine’ that inspired Spotify editor Lizzy Szabo to create the Hyperpop playlist – and the first to coin the term. With nearly half a million saves, it’s given great exposure to emerging names like ericdoa, glaive, quinn and sebii. But the catch-all phrase for the online strain of genre-less music has also become a restrictive term many of them are rejecting too. Charli XCX (funny enough), Ericdoa and glaive are artists actively distancing themselves from Hyperpop. “We’re working on killing it” glaive told VICE when asked about the future of hyperpop. “It’s happening slowly but surely.”

But why does hyperpop have to die? As with all niche genres, they somehow lose their appeal as soon as the mainstream gets wind of them. Cue Camila Cabello going hyperpop. But there is something about this genre that never quite wants to go away and has a chokehold on an entire generation.

The sound of a queer counterculture

So, what’s the big deal? An electronic sound, though integral to linking hyperpop acts to one another and solidifying what it means in the world of music, is only one aspect of the genre’s relevance in today’s society. There is an innate difference between hyperpop and other types of music that came before it, and that difference lies in its profound connection to LGBTQIA+ culture.

Marginalised groups have always been and will always be at the forefront of pop culture. It is therefore no surprise that the LGBTQIA+ community has been at the forefront of a musical and cultural movement such as this. Hyperpop rejects the status quo, relies heavily on technology as a tool and unapologetically embraces anger, joy, boredom and other distinctly raw human emotions, all linked to self-identity, often through the lens of satire and irony. A gender theme is also evident in the lyrics. Take hyper-pop pioneer SOPHIE, for example. In songs such as ‘Immaterial’, she explores the relationship between gender and the body, or describes how identities are becoming more fluid in a digital world. Some hyperpop musicians also work with irony and exaggeration. For some musicians in the genre, it’s a matter of persona; a front created to better represent the parts of themselves that are over-regulated by society, similar in nature to the act of drag performance in that it’s meant to exaggerate, uplift and rebel against social constraints (such as people like Dorian Electra, Kim Petras, Charli XCX, Rico Nasty, etc., whose allure and unapologetic embrace of modern taboos carries weight alongside their music itself).

The genderfluid person’s songs parody ideas of masculinity as well as homophobic and queer-hostile conspiracy theories. For example, the abstruse claim that the US government would add hormones to the drinking water to make the population homosexual. In fact, hyperpop is largely produced by people who do not always identify with mainstream society. The majority are trans or non-binary. Elyotto, for example, has come out as trans. So is Laura Les, one half of the successful hyperpop duo 100 gecs. The fact that many of the musicians are queer is also reflected in their music. Vocal distortions, for example, are often used to play with gender identities.

Hyperpop is a structurally reactive phenomenon. It seeks to find new entry points into the mainstream, with the ambition to simultaneously drain experimental music of its elitism and exclusivism, while making mainstream music more challenging and boundary-pushing.

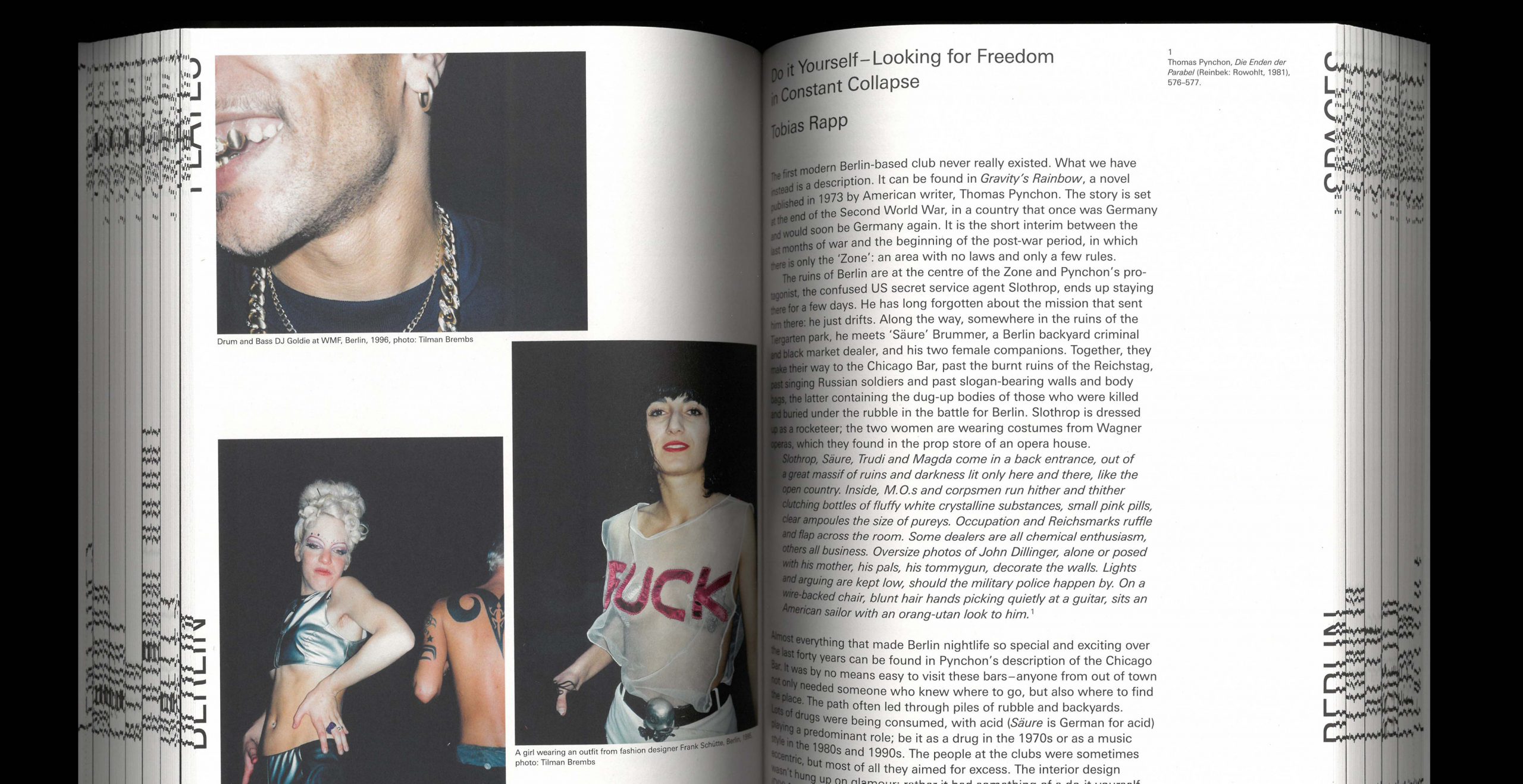

***Credit Header Image: SOPHIE