“How are you arriving today—and what do you bring in your heart?”

That’s how I began my conversation with artist and author Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju on a quiet Saturday afternoon at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, where her work is currently on view in the exhibition Musafiri: Of Travellers and Guests. She smiled, answering with honesty and ease—naming the small rituals that anchored her that morning, the warmth in the early spring air, the rhythm of rest held alongside the ongoing intensity of her artistic practice.

The question of arrival felt fitting—not as a metaphor, but as a lived condition—one that recurs throughout Ilupeju’s work. In Musafiri, where themes of movement, hospitality, and refusal unfold across different geographies, arrival is never just about physical presence. It’s about lineage, displacement, grief, joy, and the quiet rituals that allow one to settle, even temporarily. Ilupeju’s contribution, consisting of three paintings rendered on cowhide leather, doesn’t seek to represent this condition. It inhabits it.

Later this summer, Ilupeju will present a new sculptural installation at Art Basel Statements—an ambitious, large-scale project that marks a significant moment in her trajectory. Here in Berlin, her focus was rooted in a different kind of attention. The paintings shown in Musafiri move with intimate gravity through memory and embodied experience.

“I think painting, for me, is a way of metabolizing something I haven’t fully processed. It helps me understand what I’m carrying.”

The Ritual of Arrival

“I think a lot about who gets to arrive,” she said. “And how. And with what kind of grace.”

The exhibition’s title Musafiri, the Arabic word for traveller, evokes not just mobility, but invitation. In several languages, including Turkish and Romanian, the word also means guest—someone received, often temporarily, into another’s space. What does it mean to be a guest in unfamiliar territory? What does it take to cross a fictional border and be received with care?

Curated by Cosmin Costinaș, Musafiri engages hospitality as both gesture and structure—tracing how access, movement, and belonging are shaped by invisible permissions and inherited privileges.

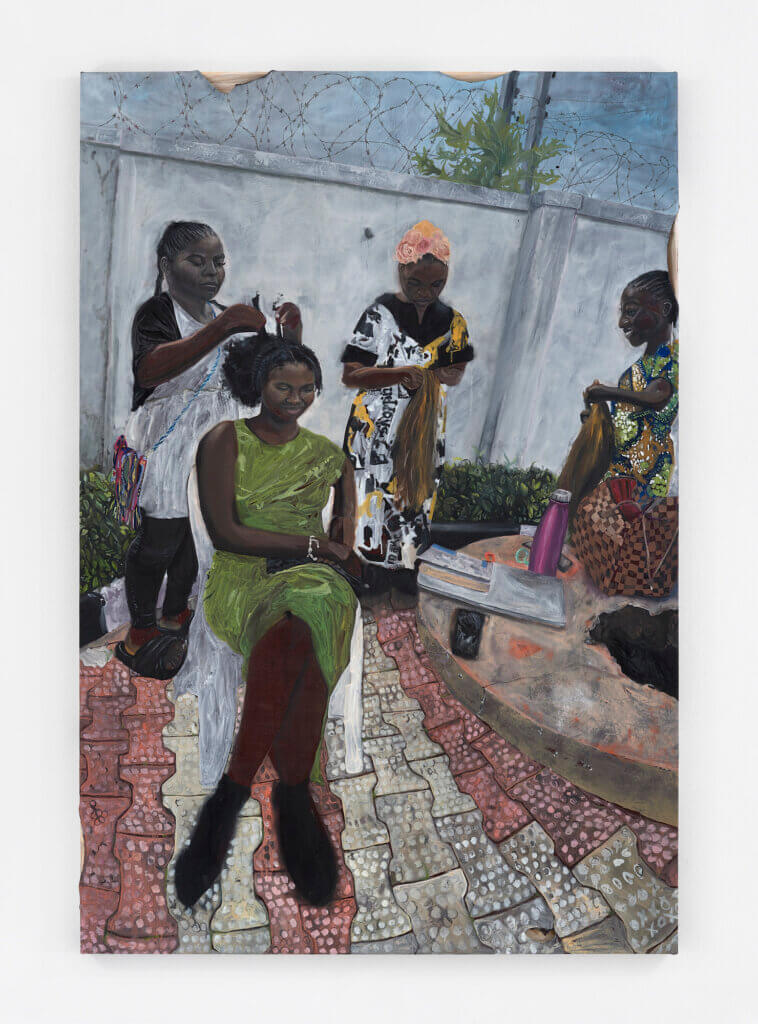

In Box Braids at Uncle’s Arba’in (2024), Ilupeju paints herself getting braids during a family gathering in Ibadan, Nigeria. It was her first time in the country, and the occasion was a Muslim memorial ceremony for her late uncle.

“I had just arrived. Everyone was mourning, praying, eating. But the atmosphere was surprisingly casual. After the prayers, I was anxiously waiting to get my hair braided,” she recalled. “Eventually, my aunt looked at me and said, ‘Here, we relax.’ I had to leave New York and Berlin behind for a moment and enter this slower pace.”

When the braider arrived with her daughters in the early evening, Monilola was met with tenderness. “It was the most beautiful set of braids I’ve ever had. Waist-length, ginger, knotless, soft. They were fast and it didn’t hurt. They were so kind. It felt like communion.”

In that moment, the everyday act of braiding became a ritual of trust and care. “You don’t let just anyone touch your head,” she said. “My mother always told me that—because that’s where energy moves, where spiritual vulnerability lives.”

Box Braids at Uncle’s Arba’in (2024), Photo credit: Eric Tschernow

Ancestral bonds

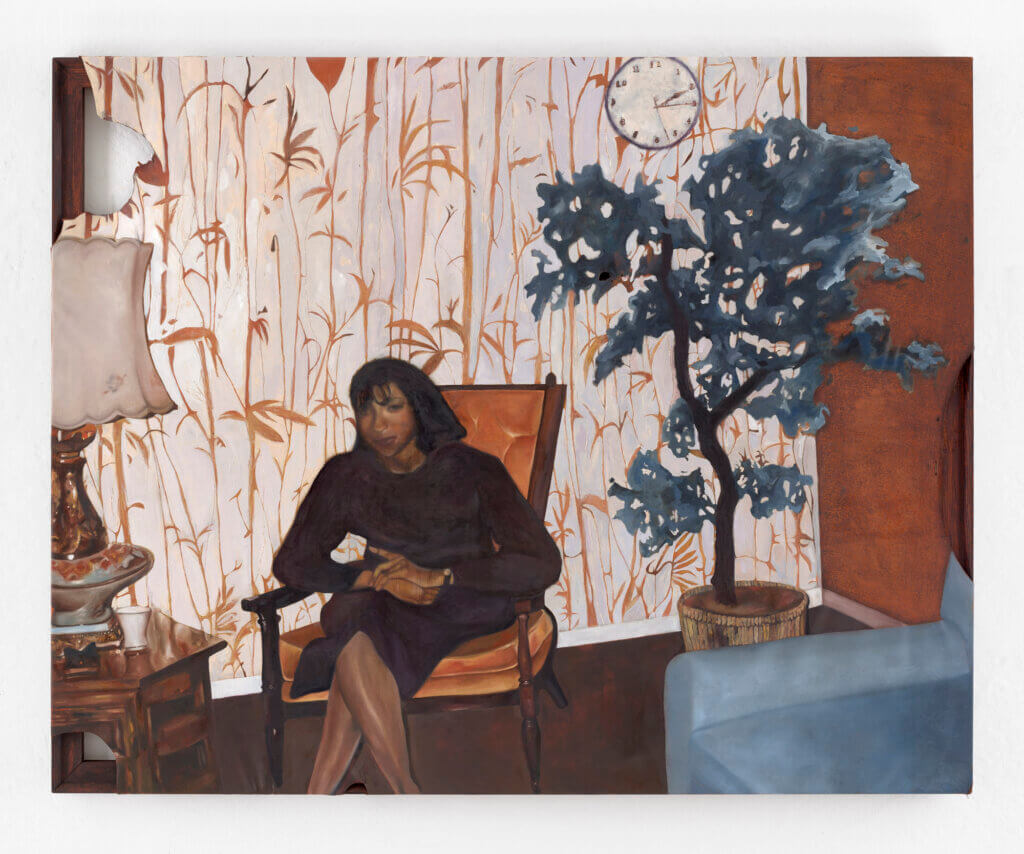

Next to the braiding scene hangs V. & Blue Tree (2024), a painting of her mother at age 21—captured just after she migrated from Nigeria to the United States. “It was based on a strange photograph I’ve always been fascinated by,” Monilola said. “The green tree in it turned blue during development. My mother looks beautiful, but also awkward. Like she’s still figuring out who she is and what her life will entail.”

Monilola was the same age (21) when she moved to Berlin alone. “This painting became a way to metabolize my own anxiety about the future,” she said. “I was trying to imagine what she was feeling then. What I was feeling now.”

The result is not just a portrait, but a mirror—across generations, across geographies, across moments of becoming. “We often carry questions our mothers couldn’t answer out loud,” she said. “The painting became a space to hold them.”

Leather as Archive

All three of Ilupeju’s paintings in Musafiri are made on cowhide leather—a material she turned to after years of painting on canvas and experimenting with figural cutouts. The shift began, fittingly, with an object full of memory: an old thrifted backpack she’d carried for over a decade.

“It was always open, always breaking. But I never lost anything. That openness became a metaphor for vulnerability.”

When she finally brought the worn leather into her studio, something clicked. “I scratched into it, and suddenly it felt alive. All the years, all the marks. I could paint on it, burn into it, write into it. It holds everything.”

Unlike canvas, leather resists polish. It shows its age, its scars, its use. “It’s skin. Something lived. I like that you can’t make it perfect. That’s what makes it beautiful.”

She sources the hides consciously; either secondhand, or from organic farms where the leather is a byproduct, not the purpose. Still, she doesn’t deny the ethical tension. “No matter how you justify it, something died. That’s part of the confrontation.”

There’s also a deeper layer—an economic and cultural erasure she’s beginning to investigate more directly. “So much leather in the luxury industry once came from Nigeria, but was relabeled as Italian ‘genuine leather.’ The Nigerian labor was made invisible. I want to research this more—find vintage designer bags, deconstruct them, paint on them. Return the story.”

Poppies and Uncanny Fields

The smallest work in the series, dust floating above my head like gnats in a daze (2024), is based on a found image of a poppy field. “The flowers looked like zombies or people,” she says. “Some were kissing. Others were floating. It felt uncanny.”

Poppies—beautiful, medicinal, deadly—carry long histories of empire, extraction, and pain. The painting holds that residue. Branded into the leather’s edge is a line in Monilola’s poem End of Summer Vigil from her book Earnestly (Archive Books, 2022), which also gives the work its title. “I wanted to understand the plant. How something so lovely could also be turned into a site of destruction.”

It’s the only piece in the trio that avoids the human figure, yet it may be the most haunted. It vibrates with absence—and with spirits that drift just outside the frame.

A Spell for Forgiveness

Toward the end of our conversation, I asked her what kind of spell or prayer these works might be casting.

She didn’t hesitate.

“Forgiveness,” she said. “Real talk. For what I did and didn’t do. For what others did and didn’t do. Or couldn’t. For the misunderstandings. For the silence. For all the gaps.”

Her paintings don’t close those gaps. They mark them. They stretch across them. They offer a kind of skin we can touch—tender, irregular, resilient.

“I love theory, but I get tired of the pressure to be overly theoretical,” she told me. “I can’t be clean or conceptual all the time. I make art to live, with the grief, the joy, with all of it. That’s the truth. It’s what saved me.”

Ilupeju’s works in Musafiri don’t offer conclusions. They offer conditions for presence. In the flesh. In the process. In the contradictions that don’t need to be resolved to be real. They hold the body—scarred, adorned, in transit—and speak without needing to explain itself. And maybe that’s what Musafiri makes space for, in the end: not just arrival, but reconciliation. Not just hospitality, but grace. The fact that it lives—through the rituals, and the choice to continue—not despite it all, but because of it.