Those who grew up in Central and South America have been acquainted with Frida Kahlo since their early years. The image of a Mexican woman whose talent and audacity made a breakthrough in the art industry with self-portraits, in which her beauty isn’t enhanced and her sorrows aren’t hindered, has meant for many, including myself, the possibility to be seen for our creative minds and not just for our bodies. To make it through as a female artist in this geopolitical area—to this day—is a major accomplishment, and the story of Frida Kahlo gave many the hope to pursue art against all odds. Looking back in time, Frida has contributed to turning Mexico into the Mecca for female artists, a place that saw a surge in female artists migrating to the big city from other countries in the ‘80s and ‘90s, hoping to make it eventually into the U.S.

The image of Frida Kahlo, however, isn’t anymore the same as it was before. As it happens with iconic artists who suddenly become a cult, such as it is slowly happening now with Ana Mendieta, the rise of ‘Kaohlism’—the cult of Kahlo—has massively replicated, commercialised, and taken out of context Kahlo’s self-portraits, and in this process, turned her image into a kitschy, mainstream emblem of Mexican identity—similar to the tribal-like painted skulls for dia de los muertos. And so the story about who the artist really was and what her paintings meant to her has been missing from today’s hype. With all this cultural and media baggage on her shoulders, Carla Gutiérrez enters the landscape with yet another production about Kahlo.

The New Frida Documentary

Titled Frida, Gutiérrez’s documentary tells the story of Kahlo from Kahlo’s own perspective. With a first-person approach, read by Mexican artist Fernanda Echevarria del Rivero, the documentary’s linear script is based on Kahlo’s diaries, letters, essays, interviews, and conversations with sources close to her legacy such as Diego Rivera’s grandson, Gutiérrez dives successfully into the artist’s inner world, making tangible the correlation between her pains and her daily event, and the way they summoned up in Frida Kahlo’s artwork.

“I paint the reality as I see it. Through no one’s eyes but my own,” writes Kahlo in her diary. “My feelings, my moods, and my profound reactions to life.”

Not only does the new Frida documentary (2024) do a good job of unveiling the intent and drive behind the artist’s pieces from her perspective—which to Kahlo is not to be confused with surrealism—but it offers insight too into the complexity of her thoughts, pains, fears, and passions, which ultimately make it easier to connect with her story—that of a regular woman trying to figure things out. It goes from her imprudent questions as a kid and the bus accident that kept her in pain throughout her life, to having to terminate her pregnancy due to her physical condition because of the accident, her love for Diego Rivera, and her disdain for the bourgeoisie and the artsy people.

A clear instance is when she talks about the French Surrealists, or the “Surrealist cacas” as she dubbed them, to whom she was associated at the time, describing them as “a decadent manifestation of bourgeois art,” adding that, different from them, she didn’t paint her dreams but her reality. Kahlo’s foul-mouthed personal entries have surprised many—as per what I’ve read on the internet—adding a new layer to the way we think of her, as gloomy and unimpressed.

What’s New About this Frida Documentary

But what I’ve enjoyed the most from this take is that Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera’s love isn’t at the centre of the story. Although their relationship went on for most of Kahlo’s life, past productions depict their explosive love as the ongoing basis for Kahlo’s existential meaning, creative inspiration, and life decisions. Which isn’t that far from reality. But as it defocuses the attention from her partner, we get to hear more about Kahlo’s intimate moments with other people of various genders and in that, we get to see more about her queerness and the way she revolted consciously or not against social norms. Her ability to take pleasure from these encounters, without any catholic guilt, and regardless of her disability caused by the accident, has certainly earned her a spot in the altar of queerness—for good reasons.

The Frida documentary streaming now on Amazon Prime, which debuted at the 2024 Sundance Film Festival in January, hasn’t received much commentary, and I’m thinking this might be because of Kahlo’s content overload everywhere that automatically underestimates the value of new productions. I was myself unsure of watching the new documentary, and even more, unsure of writing this piece. But now that I’ve done it, all I have to say, Frida is definitely all about her perspective.

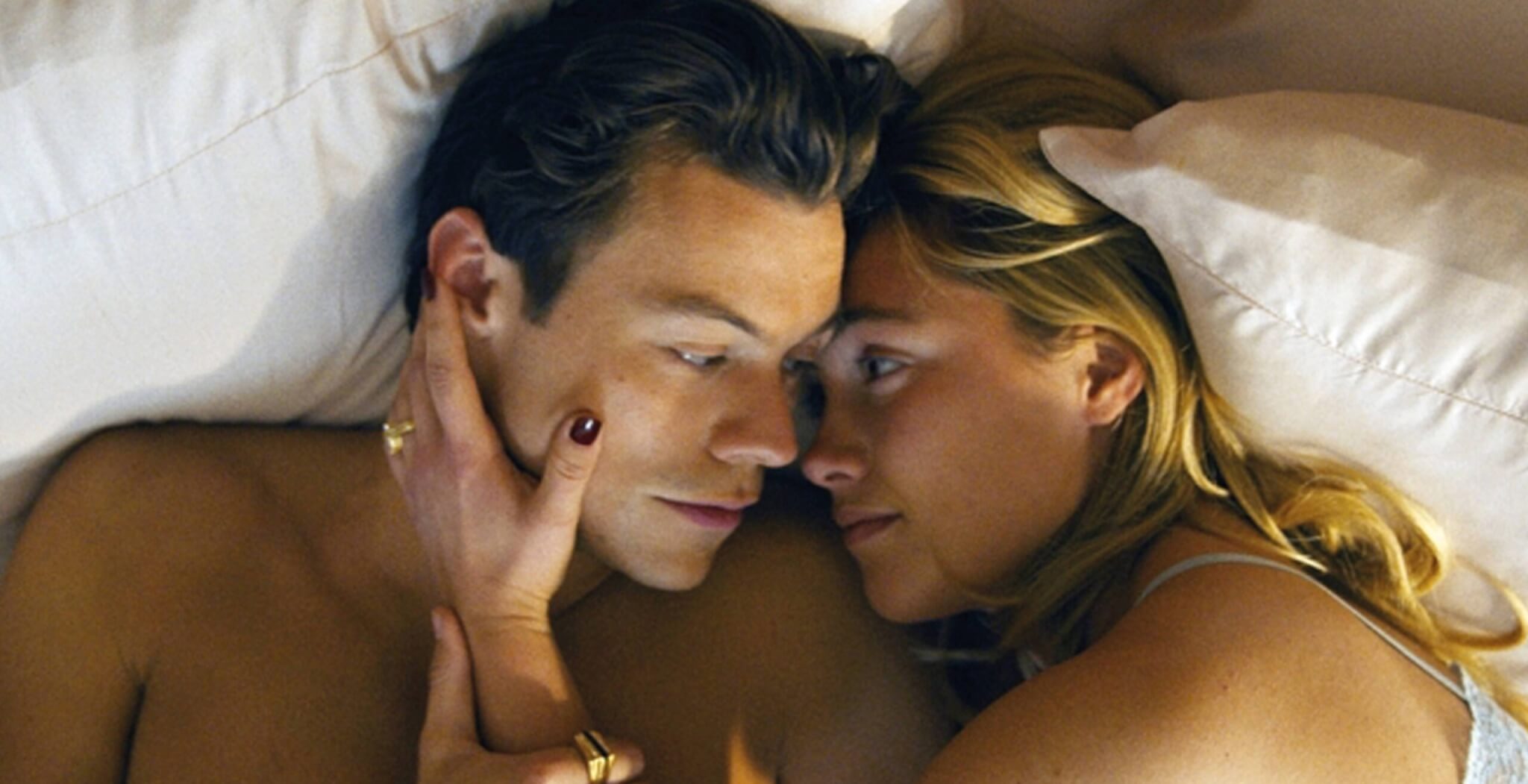

*Header image: from Frida documentary by Carla Gutiérrez streaming on Amazon Prime (2024)