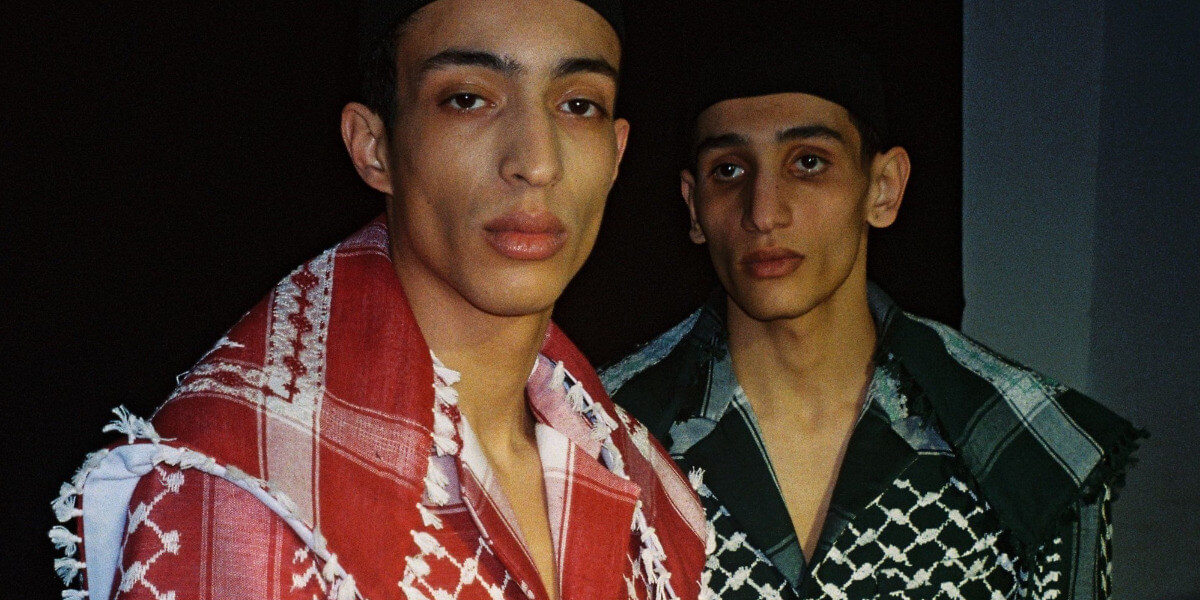

“As fashion designers, we’re normally left to express our thoughts through clothing and leave the rest to the imagination. But we live in dangerous times where the precision of words is needed,” read GmbH founders Serhat Işık and Benjamin A. Huseby, in a statement shortly before their show “Untitled Nations“ at Paris Fashion Week last week. GmbH, a Berlin-based brand with an activist approach, tackling topics related to migration and heritage, diversity, stereotypes, and identities, used their platform at Paris Fashion Week to make a political statement and call for peace. They showed a collection charged with political symbols, including the colors of the Palestinian flag, tailored jackets made from reworked Keffiyeh, and prints of a deconstructed United Nations logo.

While fashion has always served as a social barometer and mirror of society, recent crises have led to a turning point and made it clearer than ever: fashion cannot withdraw from politics. Fashion always reacts to its time, and our time is characterized by uncertainties, ambivalences, and simultaneities that are often difficult to bear. So how does an industry driven by hedonism and luxury face up to the multiple global crises of today?

Although fashion often seems like a parallel universe next to a multitude of global crises that are happening, one has been particularly close to fashion events. Generally, in the West, a lot of these crises and wars are not covered enough in the media, but when the war broke out on the Eastern borders of Europe, it shook the fashion industry.

When Russian President Vladimir Putin launched his violent invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, just a few hundred kilometers away, Milan Fashion Week had just begun. While the first shocking images of the horror caused by Putin’s brutal attack on Ukraine go around the world, the Fashion Week, glamorous as ever, celebrated its comeback after a long break due to COVID restrictions.

While luxury brands at Milan Fashion Week were criticized for their apparent indifference, as business continued as usual (with the exception of Giorgio Armani who refrained from playing music during his show out of respect), other brands at Paris Fashion Week, a few days later, were quick to catch on and show solidarity with Ukraine: the Ukrainian colors yellow and blue were seen on the runway at Coperni and Louis Vuitton; a moment of silence at Cecilie Bahnsen and accompanying statements to the show took place. Or, as Demna did for Balenciaga, dedicated the entire collection: a dystopian snowstorm, with parallels drawn from Demna’s own experience of war and flight, as he too has fled from a war in Georgia in the 1990s, accompanied by a statement of solidarity with the people of Ukraine, and a comment on the situation: “Fashion feels like some sort of absurdity.”

Silent and loud forms of statements and protests take place, the industry’s big players announcing boycotts in Russia and donations to Ukraine, following the actions by our governments, showed the intertwining of fashion and politics.

Two years later, with another war raging in front of the world’s eyes, this time in the Middle East, Fashion Weeks are back to their usual pace, glitz and glam, and a deafening silence. While on social media and the streets of many cities across Europe and the world, people are protesting, discussing, and educating themselves, luxury brands mostly stay quiet during Fashion Week.

Looking at the recent cancellations of events, shows and exhibitions in Germany of artists, musicians, and writers due to their views on the Israel-Palestine conflict — or just their own heritage — it becomes clear that it takes a lot of courage for a public figure to voice their opinion on the conflict.

For instance, Berlin photographer Rafael Malik’s photo exhibition in Berlin, documenting different facets of Muslim life in Germany was canceled by the venue for representing a “one-sided presentation of Muslim life without a corresponding counterpoint, which, for example, focuses on Jewish life in Berlin.” The cancellation states that the team is aware that the photo series has nothing to do with the current political situation, but has nevertheless decided to cancel it “in order to avoid conflicts.”

Oyoun, a non-profit cultural center in Berlin, which organizes artistic-cultural projects through decolonial, queer * feminist, and migrant perspectives, is fighting for survival after the Berlin senate withdrew its funding in November, following an event hosted by Jewish Voice for a Just Peace in the Middle East, to commemorate both victims of Hamas terror and Israeli airstrikes in Gaza.

Candice Breitz, a South African and Jewish artist, who explores ideology, racism, apartheid, and other global issues in her work, and recently showed her exhibition Whiteface at Fotografiska Berlin, became a subject of an uproar in the art scene after her new exhibition which was planned at the Saarlandmuseum in Saarbrücken was canceled by the Stiftung Saarländischer Kulturbesitz (a state-sponsored institution) due to controversial statements in the context of Hamas’ war of aggression against the State of Israel. The artist had criticized both Hamas and the right-wing government in Israel.

The institute’s reaction and immediate cancellation of her exhibition have triggered a nationwide debate on the subject of freedom of expression and artistic freedom.

In light of all this, there is a lot at stake in doing what Huseby and Işık did, call for “a ceasefire now, a release of all hostages, a free Palestine, and an end to the occupation.” As they said in an interview (at one of their shows) six years earlier, they are not afraid of being political, and believe “in the political and formal possibilities of fashion as a medium of intercultural exchange.”

And the times are calling for it. With rising death tolls in Gaza, as well as the rise of Antisemitism and Islamophobia, of nationalist and far-right parties in Germany and across Europe, activism is more important than ever.

Nevertheless, just to state the obvious here – yes, fashion is first and foremost a business, a trillion-dollar industry to be precise, which has been and still is driven by the primary aim to make a profit, and therefore often shies away from any topic that could cause controversy, so as not to hurt business. But looking at this industry as part of an economy and part of an exploitative system, the political dimension is implicit per se and cannot be ignored. In other words, you can’t take the political out of fashion, so make it more visible instead.

And further, being such an impactful industry, financially as well as socially, receiving attention, especially among a rich audience (and those who didn’t come for politics but for status symbols), it can promote ideas and bring awareness to a broader audience.

Throughout fashion history, there are a lot of examples proving the power of activism through fashion, from the Women’s Suffrage movement to the Black Panther Party, and fashion’s favorite punk, activist and queen of political fashion: the late Dame Vivienne Westwood.

Known for her controversial, radical, sometimes vulgar approach, Vivienne was one of the most influential fashion designers of her time, who never shied away from using her platform for activism, tackling topics from climate change, gender norms, democracy and racism to ethical fashion, and providing comments on UK-politics, while always staying true to herself and her style.

All of this to say: it has been done before and it can continue to be done – using fashion to promote change.

So, in times of all these crises, when everything seems pointless and sometimes I ask myself, why even work in fashion, why not do something more useful? It is activism that makes up fashion’s relevance and raison d’être. It can’t change the world, but it can engage with current matters that affect all of us, and in the case of GmbH, be a role model for a more conscious society.

*Header: GmbH Autumn/Winter 2024 menswear Photography by Spyros Rennt