Irina Dzhus SS25 Collection Is a Festive Celebration of Trauma

This season’s Fashion Week in Berlin has astonished many with elevated designs, intricate concepts, and shows that defy norms and expectations of what fashion presentations look like. If every fashion show is about curating a world on its own, Irina Dzhus, the creative mind behind the conceptual clothing brand DZHUS, put on a show in which a wide range of emotions, from sorrow to agony and release, swallowed visitors up into a ritualistic moment of transformation.

Characterised by the possibility of transformation since its inception, the Ukrainian-now-based-in-Berlin brand’s SS25 collection mirrors Irina’s personal process of relocation, resilience, and trauma. In this candid interview, we talk about the thematic depth of Irina’s latest collection ‘ANTICON’, and the way it reflects existential struggles together with a creative process that doesn’t necessarily lead to catharsis and the hope for rediscovery.

Hi Irina! I’m very excited to have finally met you, after more than three years since we spoke for the first time about DZHUS. You’ve just presented your SS25 collection at the Berlin Fashion Week. What was the process behind creating this collection? And how do you feel about presenting once again at the Berlin Fashion Week?

To be honest, it’s been extremely tough.

Honoured to have won the Berlin Contemporary competition for the fourth time in a row, I’ve felt immense responsibility to meet the expectations of the experts and the entire German fashion community. DZHUS is a small brand, freshly relocated from Ukraine under the dome of the war. And even before, it was challenging to fit into the seasonal timing, considering my intricate design ideas and experimental techniques.

These four victories have driven me for a year and a half a rollercoaster, with me being fully occupied with the fulfilment of the accorded projects. It would still be just a normal industry challenge if the very first show hasn’t coincided with the beginning of my life-determining personal drama. With zero driving force and hardly surviving as a being, I still had to manage working matters and have been supposed to materialise my creative statements.

Speaking of the SS25 collection itself, it’s been a festive celebration of my trauma, my enhanced compulsions as a consequence of a severe neurosis I ended up with, and the theatrical approach I shifted to from my initial passion for modest, boutique chic. With my upcoming self-withdrawal from the industry race, I’m not going to stop working but to seize external expectations and focus on reworking details of the SS25 line, the way I imagined those from both sartorial and technological perspectives.

What are the main topics you unveiled in this collection, under the name ‘ANTICON’?

‘ANTICON’ or ‘ANTI-ICON’ refers to an existential struggle caused by a doomed strategy of projecting our own idealistic imagination onto an external subject. By definition, an icon serves as a surrogate for addressing piety and hopes—we don’t pray to the icon itself, otherwise, it would have been a totem, but utilise it as sort of an illustration of our abstract addressee.

Thus, an ‘anti-icon’, on the contrary, portrays our grief and disappointment. I’ve obtained that sensation by having once met a person somehow similar to the protagonist of my drama, and, conveniently, redirecting my agony onto this hero. A stranger’s face now reflects my multi-layered tragedy and the spectrum of emotions I experienced, and it’s contested by the factual interaction I’ve ever had with this human. We look for such anti-icons in an urge to live through our cherished experiences once again.

Having dedicated the DZHUS SS25 collection to utopia codes, I’ve alluded to a semantic database that can help us classify our imaginations—from iconography canons to commodity symbols, and road signs to their colour spectrum. I’ve desaturated the rainbow, having replaced the shades with abbreviations, and referred to society’s speculations about the pets’ afterlife. I’ve also elaborated on self-consumerism as an essential human quality. Among other narratives are the a-priori divinity of things, deriving from Gnosticism, and salvation through a range of declared rituals, referring to the Kabbalah, the metaphysical healing of the conventionalism in Orthodoxy. And I glorify ‘self-settlement’, missioned to replace a geographical home when needed.

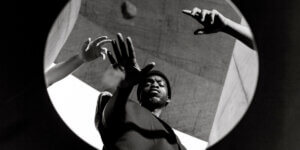

The performance was a meditative, ritual-like show—combining elements of fire and earth, tribal music, and prayers stamped on the models’ bodies. Can you tell us more about the concept of the show, the meaning of the prayers, and what it overall intended to purge—or attract?

It’s a bit more complex than described, still, I’m glad we managed to create the right imagery.

In correlation with my previous answer, I’ll sum up that the overall setting was exaggerated, quasi-spiritual, as it invited our guests to witness the mystery of the Last Supper in a life-affirming, yet thought-provoking interpretation. We’ve played a tricky game with our audience, having shown, in fact, nothing but minimalism, saturated with atmospheric elements, so people’s minds could complete the work by speculating.

The texts written on the models’ bodies and those in the brochure are my love poems, composed in order to resemble canonic verses. Not-so-known but I’ve been writing all my life—although I had a 15-year break because of a marriage that was toxic enough to discourage me completely from doing it. I do consider my poems to be on a stronger level than my designs. Thus, somehow organically, I’ve released my first international poetry book, written in 4 languages.

Looking back at your trajectory, the concept of transformation has been very present—and certainly praised by the audience. How does this collection’s multi-functionality mirror your most recent personal transformation?

I find myself living through a range of weird challenges that have affected my personality at its very core—it started with escaping the war and proceeded with a mysterious love story, and flashbacks to memories of an unhealthy experience in my family and early years filled with new-age trips and home violence. The recent events have sort of opened a channel for realisation and processing the past, which I used to block myself from, until now.

Naturally, my transforming design concepts became bolder, more sincere, and less expected. I’ve incorporated a symbolic splash of colour and embellishment that pop out from the interlayers—an allegoric evidence that there’s always more to be discovered.

A few years ago you were based in Kyiv, at the front of the Ukrainian Fashion Week. Can you tell us more about you and your brand and what’s happened since you moved to the EU after the war started in Ukraine?

I was based in my hometown Kyiv until the invasion in February 2022. Although being part of the Ukrainian fashion and design community had been an honour, I never fit the proper extent, nor had I ever experienced any personal happiness in my country. Partly, because of the mentality disconnect, as I wouldn’t call myself a typical Ukrainian, or a typical anything.

Ukrainian Fashion Week has always treated me warmly so I felt a part of the family, which is hard to overestimate. Now, I’m incredibly lucky to be granted the same approach by Berlin Fashion Week, and I’m doing my best to meet the standards.

The relocation of the HQ has facilitated the business aspect and the logistics, as DZHUS has always been an international label.

How has the displacement of creatives from Ukraine impacted your network of support abroad?

DZHUS will always remain a brand with a Ukrainian soul, and therefore, we aim to support our people with jobs and promotions. For example, the SS25 collection was entirely manufactured by Ukrainian craftswomen, whereas the show soundtrack was commissioned from a composer from Kharkiv, Hennadii Biliaiev.

The last time we spoke, you explained your garments weren’t meant to carry any political ideas. Has that changed at all?

I’m not into politics, I’m into ethics.

Neither before the war, nor after have I incorporated any political ideas into my creativity. To me, the war is not about politics but about the value of human and animal lives.

My work’s mission is to obtain spiritual growth and, eventually, contribute to the way we treat each other.

In the past, your designs were meant to be for women but looking at the most recent collections, you seem to be designing every time more gender-fluid garments. What’s been the main influential factor here, and how has that changed your creative direction?

This gradual shift in both our assortment and self-positioning is caused by several factors. Within the last years, the demand for DZHUS products from male customers has grown notably. As well, we aim to have a stereotype-free approach to self-expression.

For instance, my own identification as a non-binary person has become more public since I’ve faced drastic life circumstances. In the face of death, no space remains for hypocrisy and compromises—and here comes DZHUS as an image-making tool at the disposal of the likes of myself.

Finally, my personal drama is related to my passion for a very special male, which has inspired the menswear line and casting.

Your garments are in essence utilitarian. How does the process of ethical material sourcing challenge (or not) the concept of everyday utility?

I wish I could claim to invest so much effort in ethical sourcing that it impacts the entire production process, however, even when it comes to wholesale orders, our quantities are so small that the selected textiles are normally available. Neither do I search for something too intricately innovative as our concepts are already complex design-wise. Instead, I rather just ignore materials that don’t go in line with my ethical values and opt for cruelty-free solutions, which is an a-priori norm for me. Speaking of the very usage of the DZHUS products, since the garments offer the possibility of transformation, we rather go for fabrics that have nothing to do with the dilemma of leather alternatives, durability, or sustainability.

I’m, however, intrigued by the thought of going more into accessories one day, and then I’d start with research in future-oriented, nonviolent materials.

What’s kept you moving and what’s coming up next for you?

What has then moved me in my decision to reapply again and again? My biggest sin: greed. A good excuse though is the fact that I struggle with OCD and my case is mostly about the potential. I kind of perceive everything in the world as assets for my destination. I must constantly pick the applicable ones and coordinate them in the most efficient way. It helps me design insane, profoundly structured, multifunctional garments—but it doesn’t allow me to just live.

However, now that my desperate effort has resulted in a Spartan regime and grotesque behaviour on the edge of sanity, I took the decision to stop for a while and give myself a chance to recover, and probably, to finally open Pandora’s box of my personal trauma, which means a conscious procession towards a—hopefully—temporary social disability. I tried to combine the resolution process with work duties, which has failed and impacted other people, so I do have to make a choice.