Is the bimbo the anticapitalist dream girl we’ve been waiting for? The answer: it’s complicated.

Within every system of domination comes flashes of resistance, sometimes big, sometimes small. The current iteration of domination, what I would call the advanced society of the spectacle, is the capitalist fever dream (read: nightmare) that we are all forced to live within. Like a drug-induced afterparty hookup, we greedily shovel things into our various orifices, convinced we are moments away from ecstasy, only to wake up the next morning with a headache, a hickey, and an empty wallet (and we didn’t even cum). In the advanced society of the spectacle even solutions to the drug-induced afterparty hookup like, “moderation is key!”, become commodified, everything genuine and good slipping through our fingers like so much sand, peering at the grain under a microscope we find it too has a barcode. The moment for escape from this treacherous regime exists in the dance between hegemony and resistance. We make something new, capitalism steals it, we make something new again. It’s not punk to say you’re punk rock.

The Bimbofication Trend

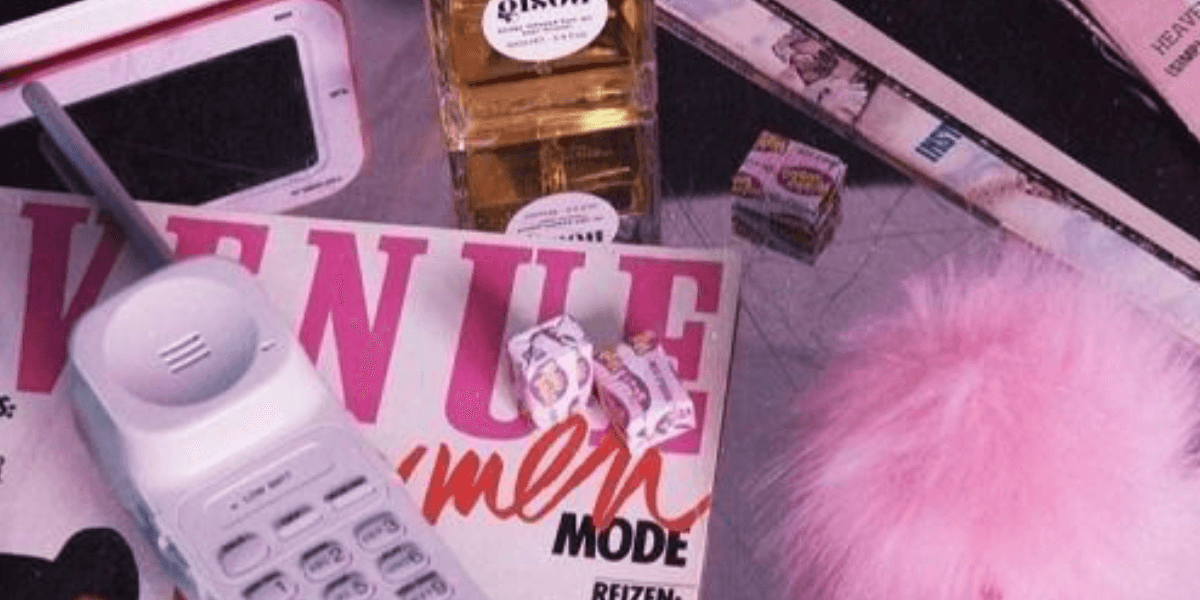

One of these “new somethings” that has been at the tip of culture’s tongue for at least 2 years now (so, not that new), is the bimbo. I know you’ve seen her. Simply put, bimbofication is a trend that has recently resurfaced on TikTok, often attributed to user Chrissy Chlapecka as one of its pioneers. The movement involves embracing the conventionally negative aesthetic tropes of the ‘bimbo’ in a celebratory, positive way. Blonde hair, revealing clothing, vocal fry, and interest in seemingly frivolous and shallow things like makeup and partying, are all classic indicators of the bimbo. Many wonder whether the bimbo is an identity, an embodiment, a performance, that can function as an act of resistance to the capitalist regime because of her seeming emergence against the #girlboss trend of 2020. Where the girlboss dreams of climbing the corporate ladder, ‘leaning in’, and assimilating to her male counterparts but with a pink Stanley Cup, the newly bimbofied subject rejects aspirations of aligning themselves with the pressures of a consumerist society that marks a person’s value by how much money they make, how much they are ‘on their grind’, and how much they commit mind, body, and soul to the all-consuming economy.

There are three answers to the question of whether the bimbo is the anticapitalist dream-girl we all want her to be: yes, no, and maybe.

“Bimbo”: From slur to feminist movement

Let us first examine the ‘yes’ answer, that the bimbo is indubitably here to free us from our neo-liberal profit-generating bonds, doing it all with a 40-inch platinum blonde ponytail and oiled pink latex. One could argue that bimbofication is in fact a practice that exposes the hypocrisy of the capitalist promise that if one goes to school, works hard, gets a job, and plays by ‘the rules’, one can escape precarity and attain the ‘good life’. If the mandate of the girl boss is to adhere to capitalism’s rules of engagement and achieve some financial success that will lead to the happiness acquired through easy access to the promises of a consumerist society, then the mandate of the bimbo is the opposite. The bimbo says ‘f*** you’ to the idea that one needs to be serious, studious, entrepreneurial, or high-achieving. Instead, the bimbo exposes the hypocrisies of the consumerist society that fuels feelings of cruel optimism and says ‘I know that even if I work hard, even if I ‘girlboss’, there is no promise of escaping financial precarity or of being satisfied on the other side even if I do’. The bimbo says that perhaps achieving the good life does not necessitate playing by capitalism’s rules of engagement as something that exists in the future, perhaps it is attainable in the now and perhaps it looks like short skirts, blonde hair, and promiscuous sexuality. Bimbofication transforms bimbo from a slur to a compliment where the “detourned autonomous element” has gone so far “as to completely lose its original sense” (Debord 1959, 67). The negative associations leveled at the bimbo; that she or he has no self-respect, doesn’t take themselves seriously, is shallow, or has a bleak future, fall flat when one realizes that even if the bimbo were a straight-edge, tie wearing, profit-oriented worker they would still not be promised a future of stability and happiness. In this sense the bimbo breaks free from a relation of cruel optimism that “makes you feel things are possible even when they are impossible” (Berlant 2011, 2).

The Bimbo’s downfall? White feminism

Now, this all sounds delicious, but unfortunately, the bimbo also has her weak spots. Let us examine then the ‘no’ answer, that the bimbo is, sadly, just another industry plug meant to make us feel like we are resisting when really we are just working for the proverbial man. There is an argument to be made that bimbofication is concerned only with appearance, and a specific appearance at that. She exists within an aesthetic of “white feminism” that is inherently transphobic, fatphobic, and racist. By leaning into markers of ‘good femininity’ that revolve around being white, blonde, thin, able bodied, sexy, and young, she furthers a dangerous conceptualization of femininity that has been employed for centuries to exclude and oppress women who do not fit the mold, reducing them in the most extreme cases to non-humans. Similarly, since the current iteration of bimbofication finds its locus in TikTok, it often involves conspicuous consumption through the purchase of pink latex outfits, hair dye, make-up, and other bimbo trappings. In a very real sense, the bimbo is about creating a marketable spectacle of oneself. One could argue that, though perhaps rebelling against what they see as the mandate to be a capitalist girl boss, the bimbo is actually just fantasizing about something that inhibits their flourishing, further feeding into the logic of the ever-oppressive capitalist economy. In this sense, bimbofication can be seen as precisely what Rancière describes as the “reign of the commodity of the spectacle” where “any protest (becomes) a spectacle and any spectacle a commodity” (Rancière 2021, 33).

Conclusion: The bimbo is politically ambivalent.

As with any media trend or instance of resistance against domination, the effects of the practice are highly specific. This is to say that while one person engaging in self-objectification through the practice of bimbofication might achieve something like anti-capitalism, another doing seemingly the same thing may not. This also speaks to the historically specific nature of resistant acts – since the rules of norms and conventions are constantly changing in different contexts, one instance of resistance can never function the same way twice. As we all come to find, the bimbo, like most things, is ambivalent. And there you have your third answer, for me the correct answer. Is the bimbo anti-capitalist? Maybe. But regardless of whether she is or not, I think we can all benefit from showing our tits, acting like a ditz, and blasting girly pop music to the dismay of all who object, even if it’s just for the fun of it.