The cuteness trend shows how digital things don’t always stay digital

«But I am not a kid!» At one point during our childhood, most of us have said some iteration of this remark to a relative guilty in our eyes of having “babied us.” While there isn’t enough money to convince the average 5th grader to go to school carrying a toy, people ten-plus years their seniors are now rediscovering their fondness for cuteness.

In East Asia, the popularity of cuteness amongst adults is nothing new. The cultural phenomenon that takes the name of Kawaii in Japan is present throughout East Asia and has been so for a long time. Unsurprisingly, internationally beloved cute characters like Sanrio’s Hello Kitty and My Melody were designed in Japan in the seventies. There and in other East Asian countries, cuteness is far from relegated to the realm of childhood: it’s in ads, pop culture, and fashion. Even the municipal-owned Seoul Metro company opted to employ a cute mascot, a blue metro train named 또타, in its communication strategy. The appeal of cuteness is obvious. Cute things catch our eye and elicit positive reactions. In short, they make us go «awww»: a mighty power in our attention economy.

While the Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe won’t be putting a cute mascot all over its communication materials anytime soon, cuteness has been gaining ground in the West online and offline thanks to Gen Z. It’s primarily because of young people’s newfound interest in all things cute that since the breakout of the COVID-19 pandemic, cute styles and products have become online trends and part of youth culture.

If the catchiness of cuteness were ever contested, its potential for online virality would be enough proof. The Sunny Angel craze was probably on nobody’s 2024 bingo card. Yet, thanks to its digitally active community of enthusiasts, these headwear-wearing cherub mini-figurines were the protagonists of shortages and even had their SNL moment. If a TikTok video of someone unboxing a surprise box containing a cute tiny doll is not the sort of consumerism-driven, quick dopamine fix that algorithms love, I don’t know what it is.

While nostalgia is probably the first reason that comes to mind when looking at our ever-increasing love of cuteness, another reason is how well-suited it is for social media. Think of the popularity of the Sylvaniandrama TikTok account. The sheer amount of figurines, sets, and accessories employed to tell the deranged adventures of its anthropomorphic animal toy protagonists makes for an oddly satisfying visual experience: a perfectly timed, eye-catching hit of curated escapism.

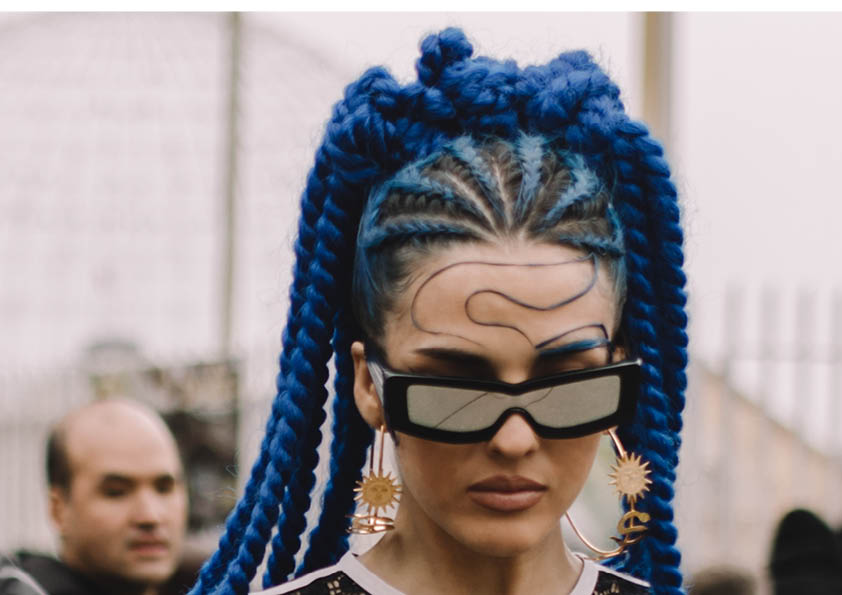

The current social media-fuelled significance of visual communication has also allowed cuteness to make its way into Western fashion. In our globalized world, trends travel across state lines effortlessly. So, given the popularity of Japanese and Korean culture, it’s no wonder that the cute styles that have long been popular there have become trendy in the West, too. The timing is no coincidence, though.

The internet-born Dopamine Dressing trend, unlike the countless micro trends of 2023, might have a lasting impact, with the online fashion world this year focusing more on personal and unique styles but not without a penchant for the kind of noticeable, bold elements that do well on visuals driven platforms.

These converging factors have given way to fashion moments like GCDS collab with Hello Kitty, the one between My Melody and Lazy Oaf, and internet darling brand Baggu’s Peanuts collection. The Y2K-era trend of loud bag charms has also re-emerged in its cuter iteration, taking center stage in the “in person” fashion world becoming one of the most noticeable trends from this summer’s Copenhagen Fashion Week. Not to forget the current Labubu trend.

We can’t say if cuteness will stay in fashion or if it will be something we leave to children once again. Either way, its time in the limelight has highlighted how, for better or worse, the line between the online and real world is ever so blurred. What we love and what performs well on social media are increasingly becoming the same. Even for those who aren’t “chronically online.”