‘Bruja’ means witch in Spanish and it’s a word that dates back to colonialism, used to demonise the spiritual practices of Indigenous peoples. During the centuries of colonialism in Latin America, the Spanish crown condemned those praying to spirits or performing intention-based practices on the premise of going to hell. But to this day the term carries a special meaning for many Latinxs as it points to our belonging within magical communities and the affiliation to several spiritual lineages, including those brought by the enslaved African people such as Voodoo.

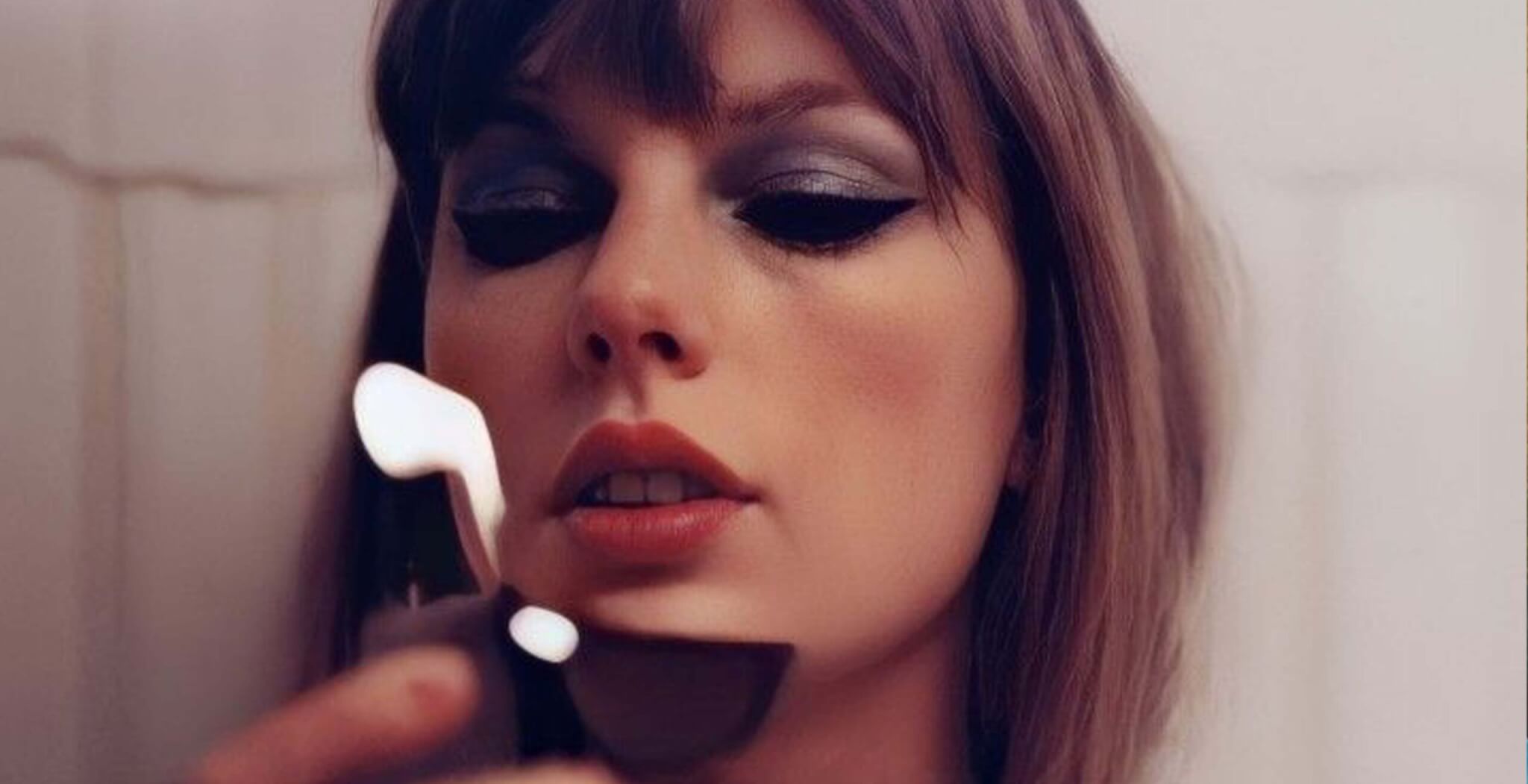

Witchcraft has been intrinsically associated with women who have a deeper access to the language of the supernatural world. Witches are holders of spiritual knowledge but also sinister forces and in most cases, their practices corrupt the social order. They defy morality, God and natural laws, and that’s why they live in a state of affliction, threatened with extirpation. Over the last decades, witches have become a popular symbol of fear or inspiration. The exploitation of their image in pop culture has many faces — from spooky looks featuring long nails and brooms to irresistibly seductive and a mysterious yet charming she-can confidence often read as she-devil.

In Gretel & Hansel (2020) a girl is gifted with supernatural abilities after being cured by a witch, and what comes after is the result of a pact with the devil. Years later, villagers find out that she’s been murdering innocent people and she’s abandoned in the woods. Based on the German folklore tale “Hansel and Gretel” by the Brothers Grimm, the witch lures children in with candy and other rich food that will fatten them only to turn into young meat. But while the witch in Brothers Grimm’s fairy tales provides maintenance to children, other witches only awaken horrors. The Witch (2015) compiles all the obscure myths around the practices of witches, especially during the witch trials between the 15th and 17th centuries in Europe: stealing children; using skulls and bones as ornaments; engaging in sacrificial rituals with goats; drinking blood; laughing maniacally.

But the history of witches in pop culture is not only one about bad witches and evil acts but about hostilities and tensions in a patriarchal society that’s at odds with women, and witchcraft has historically been a way for women to step outside the bounds of society — or to fully reinforce it and conform to it, as seen on Bewitched. The American sitcom tells the story of a beautiful witch named Samantha who marries a regular man — plain and ordinary and ready to be pleased. Like sitcom I dream of Jeannie, which aired around the same years (1965-1970), Bewitched’s femme protagonist is depicted too as simplistic, insecure and manipulative. An upgraded formula for a witch, better than the scary ones: compliant but extraordinary and therefore wifey material.

The representation of witches, and more specifically of witches as women, has been conjured as the antithesis of womanhood for they steal and eat children and enjoy inflicting suffering more than providing protection and care. They are the nightmare and not the dream. But more empowering views of women connected to their spirituality are replacing outdated forms of seeing witches as either deviant from gender norms and social order or likeable in their ability to cast spells while beinga woman. Sabrina the Teenage Witch tells the story of a teen who moves in with her two aunties to learn the art of magic, but the three of them together often cause more chaos than they solve. The nineties TV show is about female relationships with a supernatural twist, reconciling the misfortune of women living in a patriarchal system, sitting by the devil.

Going back to the introductory point, other magical depictions of witches aren’t fantasies or myths but historical processes of colonisation and abduction of rituals and beliefs. In “Brujas,” Princess Nokia’s single that came out in 2016, the spiritual ancestry of women of the African diaspora is highlighted:

“I’m that Black a-Rican bruja straight out from the Yoruba

And my people come from Africa diaspora, Cuba

And you mix that Arawak, that original people

I’m that Black Native American, I vanquish all evil”

The video starts with five women in a river in reference to Yemayá, the female water spirit of the Yoruba religion. Princess Nokia, proud of her roots, renders a homage to the beliefs of her ancestors and the terrifying beauty of being a woman in a context of ritualised ‘spell-work’ which, needless to say, is also a warning to those who oppose their way. While the single is about the history of colonialism, it is also an empowering tune for femmes to trust their spells, an ode to the shifting perception of womanhood in society today.