What happens when fashion designers move their operations to labs? That living organisms become their means and final materials to design. From fermenting bacteria to growing mycelium, the next fashion will breathe and live like plants, with the latest innovations using algae.

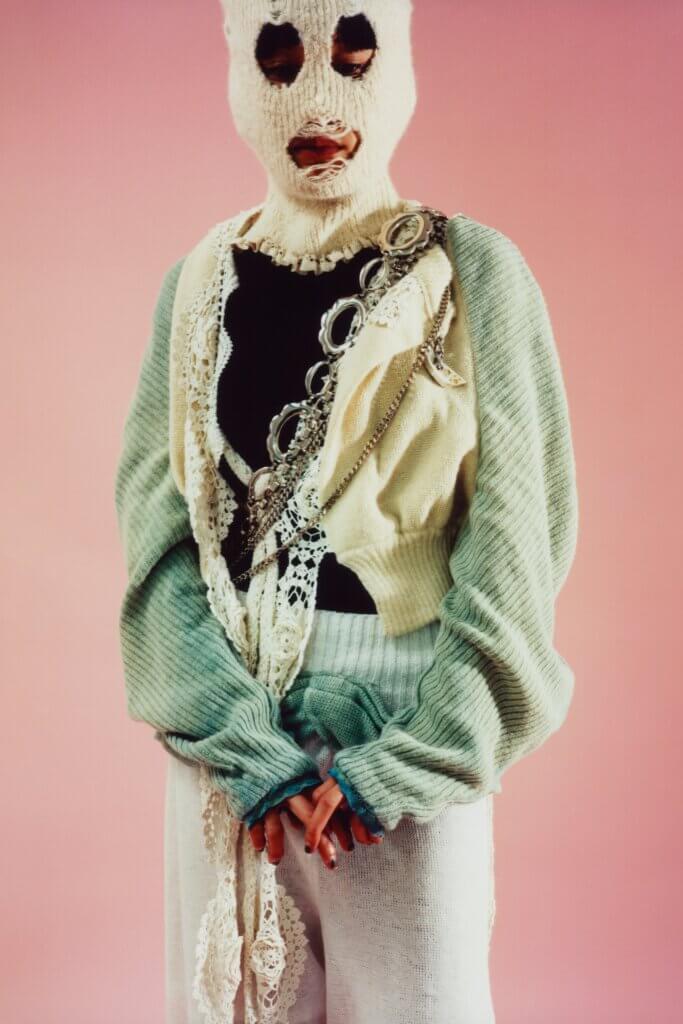

London College of Fashion graduate Olivia Rubens has made it to the headlines lately for her ‘positive knitwear’, in which garments need direct sunlight and misting to photosynthesise, completing the cycle of emitting oxygen and absorbing carbon dioxide. Rubens’s collection, which name honours the process itself, Photosynthesize, literally knits together layers of alpaca wool, Tencel, organic cotton, vintage crocheted lace tablecloth and ceramic kitchen utensils, among others, each of which tells an evocative story of their past.

Earlier this year, the Canadian designer collaborated with concept store Machine-A and biotech startup Port Carbon Lab to create the ss22 collection, which went on sale in April and quickly sold for around $300 each piece. Besides selling at Machine-A, Rubens’s biomimicry is joining the experimental forces of design at APOC STORE with pieces that draw clear inspiration from the 18th century and rococo aesthetics.

But if you were wondering whether algae-based fashion is a 2022 invention, the truth is that a lot of previous research has been done on the subject, with positive outcomes including formulation of food, cosmetics, fertilisers and even biofuel production — so why not in fashion, too? This question led Roya Aghighi to use modern biology to integrate algae in her collection Biogarmentry, a project that aims to protect the human body and improve the immediate environment of the wearer.

Designers like Aghighi invite people to shift their desire for consuming fashion as dead objects to integrating the art of dressing up as an essential part of looking after themselves altogether with what they wear. The rather ethereal-looking pieces of Roya were shortlisted in the sustainable design category in the Dezeen Awards 2019, and for the past two years, her name is linked to not only sustainable fashion, but to the future of fashion in general.

The common feelings of the industry are that material research and development are much needed to meet environmental demands, however, aesthetics continue to block the widespread adoption of climate-positive and plant-based materials. Only look at the first big case of biodesign in fashion, when Suzanne Lee literally grew bio-leather in her bathroom in Brooklyn a decade ago, by fermenting bacteria. While it sprouted a DIY movement, the commercialisation of such practices or their adoption as seen on the catwalk barely exists.

The fashion industry isn’t an easy one to cater to, especially with its strong focus on looks and feels that are hard to replace with materials that are just in their conceptual stage. But if something remains true, the possibilities that biodesign can enable are turning biology into a basic toolbox for designers, pointing out that there’s plenty of room to collaborate and work across fields, incentivised by hefty investments by luxury conglomerates such as LVMH, who announced an early-stage project to produce plastic-free lab-grown fur, and Kering, who is piloting low-impact alternative materials like mushroom leather, all betting on how far innovation can go.

*Head image: Biogarmentry by Roya Aghighi