Everywhere on the internet, true crime-related content is viral. Seemingly, most of us love the tea, the drama and the gore that have nothing to do with our lives, and that may be the reason why we don’t say publicly that we love the genre, that would be to admit that we have a morbid obsession with the lives of others. But no shaming, this article isn’t about whether is moral or not to watch true crime, and more about the purpose behind making those stories available for consumption.

We could all agree that what makes true crime particularly engaging is the psychological depth of these stories, unveiling the intricacies of criminal behaviour and the complexities of the legal system. What’s in the mind of people before, during and after committing a crime? How does the justice system react, and how do the victims find reparations? These are some of the questions that the genre invites us to reflect upon.

“We want some insight into the psychology of a killer, partly so we can learn how to protect our families and ourselves, but also because we are simply fascinated by aberrant behaviour and the many paths that twisted perceptions can take,” said true crime author Caitlin Rother in an interview with The Tab, discussing the way the genre can provide a safe way to explore dark topics. Learning how to protect ourselves in these situations is the main reason why women are the ones who engage the most with true crime content.

For sure, we can learn by watching and collecting ideas about what to do and what not to do in such situations. And in that way, we sympathise with the victims whilst reassuring our moral views as to what’s right and wrong. Those are understandable and highly appreciated reasons. But we also consume true crime for escapism. By immersing ourselves in someone’s intriguing and horrifying experience we escape the reality in front of us.

In that sense, our true crime obsession likely stems from a desire for new experiences outside our own reality. Dean Fido, Lecturer in Criminal Psychology at the University of Derby Online Learning, says that we look for “something that creates an element of excitement. When we mix this desire with insight and solving a puzzle, it can give us a short, sharp shock of adrenaline, but in a relatively safe environment.”

Perhaps it’s fair to remember that true crime is ultimately entertainment, and the framing of these tales are made to cater to our morbid attraction to horrifying stories that haven’t happened to us. The more details and suspense the more the adrenaline. And that is precisely what makes this genre problematic, because in doing so it tends to glorify the minds of the criminals and exploit people’s dreary experiences all while forgetting about what happens after to the victims and their relatives.

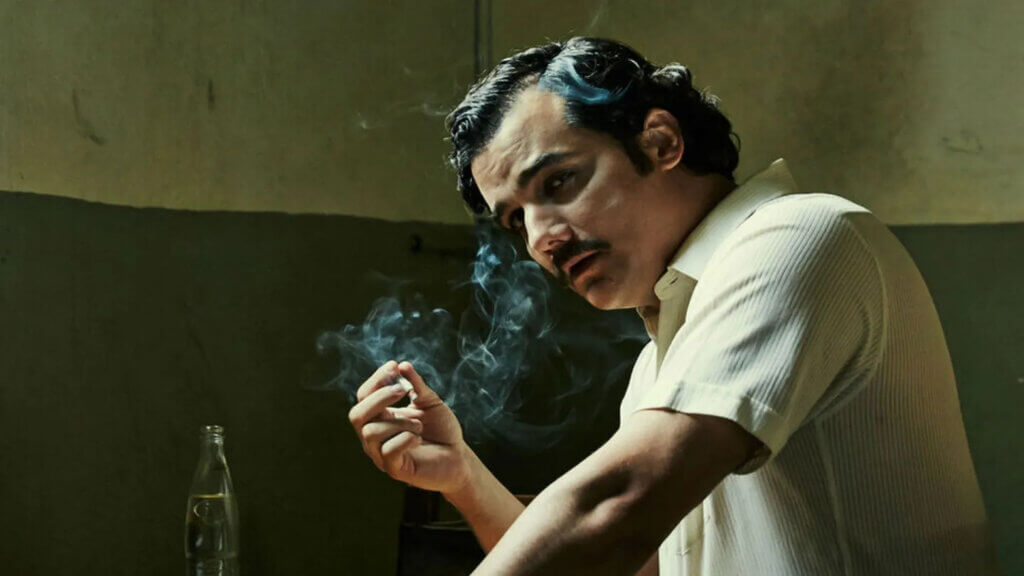

As we said at the beginning, this is not about shaming people for enjoying true crime. It’s more about questioning whether true crime is inherently immoral and exploitative, because it not only commodifies people’s horrifying experiences but also tends to glorify the role of the criminal by focusing on their astute character in order to gain viewership. A good example is Netflix’s production Narcos, which has been heavily criticised for glorifying Pablo Escobar and painting an indelible image of violence upon the country. Others, however, claim that the TV show gave a realistic insight into the cartel lord and the harm he did.

True crime tiptoes the line between glorification and realism. Sensationalism and authenticity. Research and dramatisation. And it’s important that we as viewers understand that these productions are framed in ways they can sell. I mean, would true crime be as attractive if it were not for the morbid insights they offer?

All we can say is — stop glorifying and sympathising with the criminals.

*Header image: The Assassination of Gianni Versace via BBC Two.