What maketh the men? What is unisex fashion? Do we even need a gender-specific collection?

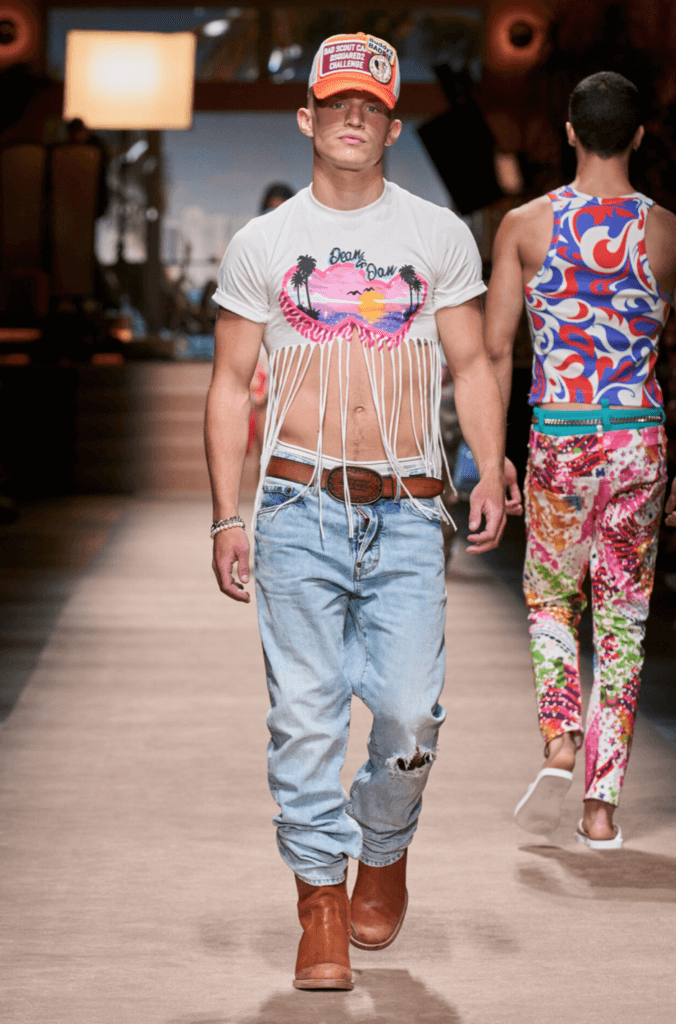

In recent cycles, the deconstruction of male identity has been at the heart of the menswear conversation, and the men’s fashion week that recently wrapped in Milan and the spring/summer shows in Paris were all about finding new ways for men to dress. The drive to dismantle traditional masculinity came this time with a reductionist bent. At DSquared there was preppy porn, complete with ‘Very Important Penis’ spelled out loud on porn star Rocco Siffredi’s T-shirt, but the brand has been cheeky and sultry since its inception. Elsewhere, the hustle and bustle seemed to reflect our prudish, even sexless, times.

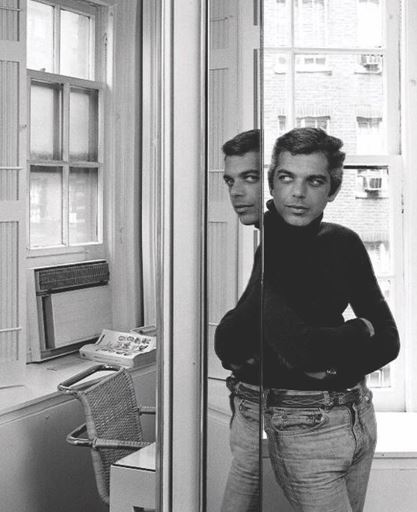

Surprisingly, Prada, the undisputed temple of robotic masculinity, made a mild acknowledgement of sexuality this season. Raf Simons’ adolescent obsessions and Miuccia Prada’s solid bourgeois tendencies, peppered with her art obsessions, came together in a way that put the body front and centre. The new male nonchalance even made its way to Berlin where Saint Laurent presented the spring/summer 2024 collection. Anthony Vaccarello has been in charge of the designs since 2016. The 41-year-old Belgian is known for body-hugging silhouettes and sharp tailoring. He tends to keep everything in black, colour is rare. For women, he is currently styling wide-shouldered pinstripe blazers, and for men, silk blouses with lapels. High heels, plunging necklines, patent leather and sheer chiffon. In the grand scheme of things, it’s a reimagining of deeply French chic; slightly scandalous, wicked, never too sexy.

But the “new” (though not quite new, more on that in a moment) male wardrobe does not stop at the runway shows. The singer Prince wore extraordinary high heels on stage. David Bowie liked to be photographed in dresses and skirts. And actor Jaden Smith wore a skirt in a Louis Vuitton campaign a few years ago. Genderfluid styling has been a fashion and social issue for some time now, especially among queer youth – but no one has caused as much of a stir as Harry Styles, who posed in a dress on the cover of US Vogue. But skirts and dresses can be found in men’s fashion all over the world. But let’s take Harry Style’s Vogue Momentum as an opportunity to delve deeper into the subject. Because even if it’s not the first, it’s certainly the most pop-cultural fashion happening.

Why was Harry Styles wearing a dress? He is the first man to grace the cover of the December 2020 issue of US Vogue, setting a milestone. Because he is wearing a dress. The bespoke ice-blue lace dress is from Alessandro Michele’s Autumn/Winter 2020 collection for Gucci, which was heavily inspired by children’s clothes. It is quite something when a young man, who also identifies as such, presents himself in a ball gown in one of the most prestigious fashion magazines. But the editorial has not only received positive feedback. What is the reason for this? Masculinity, that is, the kind of masculinity based on a traditional macho image, is no longer considered desirable – it is downright “toxic”, it is condemned as the reason for many things that go wrong in this world. Fashion, in particular, has been exploring other masculine images for years now, and a new man is being shown, tending towards androgyny. Men are allowed to wear pink blouses, floral all-over prints or sandals decorated with precious stones. However, the majority of our society still associates certain clothes with certain genders. In other words, dress equals women. It is human nature to be outraged when these well-known rules and norms are broken. But, in fact, some fashion designers have been trying to do just that for years. In the early 2000s, the crème de la crème of men’s fashion week presented various gender-fluid looks for men. Dries van Noten showed only sleeveless jumpers in his winter collection. His models’ bare arms were covered up to the elbow with long knitted gloves, as seen in women’s evening wear. Hedi Slimane, then designer of Yves Saint Laurent’s menswear, showed shirts slit from neck to waist, revealing a narrow boy’s chest. The models wore long scarves around their necks that hung down to the floor. At Gucci, blouson zips could only be opened from the bottom, revealing the stomach. And then there were the skirts! Almost every designer had one. Usually knee-length kilts or ankle-length sarongs, and yes, Yamamoto even had a knitted suit with a long tube skirt and gold-trimmed jacket for winter. The press was outraged. Enfant terrible and men’s skirt pioneer Jean Paul Gaultier has been trying to popularise the unusual male garment since the 80s. The designer himself says that wearing a skirt as a man is “a bit like skinny-dipping”. In Germany, too, there are creative people who are clearly in favour of skirts on men. One of them is the Munich designer Robert Landinger. “The skirt does not make a man unmanly,” the designer tells the world. Floor-length, closed and narrow cuts are most of his variations. They also have a simple cut, practical features such as press studs, Velcro fastenings or carabiners, and robust fabrics such as leather and linen. Although the men’s skirt has appeared from time to time in the collections of individual designers – Marc Jacobs, for example, likes to wear it, and even H&M has had one – the men’s skirt has never been suitable for the masses. The same goes for high heels. High-heeled shoes are considered a feminine item of clothing, just like a skirt or a dress. However, there are some men who defy these rules. In the online forum “Men on High-Heels”, many (male) shoe lovers from German-speaking countries can exchange views – anonymously or with their real names. In their profile pictures, they all present themselves in fancy heels. Pink, with spikes, platforms or in classic black pumps, the men’s feet pose for the camera. In the forum, they talk about their experiences with high heels or carry out internal surveys of their own shoe collection. “It can be a fashion statement, a little provocation or a real need,” says trend researcher Christiane Varga, describing the man in high heels.

The high heel emphasises the feminine attributes. “The gait changes, it becomes sexier, the hip swings with it, the leg is lengthened”. And the high heel, like the skirt, has its origins in men’s fashion. Catherina de’ Medici (Queen of France, 1547) was the first woman to wear high heels in the conventional sense. Before that, heels were a garment reserved for the Persian (male) nobility. It was only through trade and the resulting interest in Persian culture between Persia and countries such as France, Germany and Spain that the heeled shoe reached Europe. The aristocratic men of Europe then copied the style of Persian high society and developed their own form of high heel – the cavalier boot or riding boot. Later, the working class followed the trend and the aristocracy demanded higher heels to distinguish themselves from the lower classes. In other words, the higher the heel (or the less suitable for everyday work), the higher the status. A similar development can be seen in the skirt. It was not until the French Revolution that the skirt came to an end and the suit gained popularity. (The bourgeoisie wanted to distance itself from the pomp and extravagance of the aristocracy,” fashion sociologist Aida Bosch told the Süddeutsche Zeitung. But what does the historical development of high heels and skirts have to do with Harry Styles Vogue cover and the furore it caused? It proves that clothing per se has no direct connection with the gender of the wearer. Another example is Christian baptism. For centuries, all royal newborns, regardless of biological sex, have worn the ‘Honiton Christening Gown’ – a royal christening robe used by a royal family for family christenings. Even among the Romans, powerful Roman rulers wore elaborately draped togas. So did the warriors of the Masai (a semi-nomadic people from East Africa). In many parts of the world, dresses and skirts are still traditional male attire. In Russia, for example, the clergy of the Russian Orthodox Church wear elaborately embroidered robes. Demna Gvasalia once said: “How can it be that it is appropriate for clerics to wear dresses, but if I want to wear a long jacket and skirt, I will be stared at – even in 2020!” Even in China, traditional robes such as the “quju” are still worn by both women and men. The elaborate garments, which originated in the Han Dynasty in 221 BC, are currently experiencing a revival. The Shanghai Fashion Week showcased some of the most interesting new interpretations of the traditional garment. But even in India you can find traditionally embroidered men’s robes that look very much like tunics. So you can see that in many parts of the world, dresses, robes and gowns are not necessarily associated with a particular gender. But why is this not the case in countries like Germany and the USA? Conservative voices have said that the Harry Styles editorial for Vogue would feminise a classic masculinity. If that were the case, femininity would have been “masculinised” decades ago. Keyword: pantsuit. Marcel Rochas created a women’s trouser suit in the first quarter of the 20th century, but it attracted little attention. It was only when actress legend Marlene Dietrich and other Hollywood divas such as Carole Lombard and Mae West were increasingly seen wearing the casual combination of wide men’s trousers and a blazer that their choice of such masculine fashion attracted attention. To this day, their dressing style is seen as a symbolic act of liberation from social role models. The real breakthrough for the pantsuit came from Yves Saint Laurent, whose revolutionary menswear-inspired designs made it suitable for the catwalk and famous. “Good fashion designers sense what is in the air and what might be the next trend. Because fashion is always a mirror of society and the present,” says Prof. Dr. Elisabeth Hackspiel-Mikosch, Professor of Fashion Theory and Fashion History. And perhaps it is time for a similar change in men’s fashion. Our understanding of fashion is constantly changing, and a Vogue cover with Harry Styles in a dress seemed like a good place to start.

The historical development of clothing raises the question of why collections and garments are gender-coded in the first place. Of course, taking cues, hues and notes from (fashion) history is deeply embedded in design itself, but does it need to be coded? Enter: Unisex fashion. Unisex is one of the big themes in fashion – in theory. Gender-neutral or unisex clothing is on the rise. Urban Outfitters now has its own ‘unisex’ category, Zara launched its gender-neutral ‘Ungendered’ collection in 2016, and H&M sold gender-neutral denim basics under ‘Denim United’ in 2017. Meanwhile, the trend has also reached luxury brands: Gucci now has Gucci Mx, a “celebration of self-expression – regardless of gender”. But those who can’t afford Gucci are usually disappointed by its range of gender-neutral clothing – and that disappointment is starting to get loud. When the Girlfriend Collective label recently launched its ‘Everyone’ collection, which the brand describes as “everyday comfort for all genders”, it drew a lot of ire on Twitter. Why? Because the collection consists entirely of oversized loungewear in various shades of brown, from sweatpants to sweatshirts and hoodies. There is a world of difference between the actual gender-neutral range and what customers want. One of the problems is that gender-neutral is a rather imprecise term; different people have different ideas. Many people think that men’s clothing is inherently more gender-neutral – especially when worn by a woman. But this is problematic, because any piece of clothing can be gender-neutral. No wonder skirts and dresses rarely – if ever – appear in gender-neutral collections. Despite Harry Styles wearing a dress on the cover of Vogue and Billy Porter appearing at the Met Gala in a Christian Siriano gown, there seems to be no escape for skirts and dresses from the women’s section. When unisex collections consist entirely of oversized jumpers and trousers, they don’t challenge existing gender norms as much as they claim to; truly gender-neutral clothes look like everything we already wear – just without the female or male categories. So instead of launching gender-neutral collections or pop-up shops, it might be better not to gender clothes at all.

Header Credit: Backstage at Palomo Spain’s Luxe and Lascivious Fall 2017 Show With All the Boys In the Club