Corsets, garments that have been absent from people’s everyday wardrobes for nearly a century, remain a topic of interest online and a recurring feature in period dramas. Though often cast as restrictive or even risky, corsets continue to resurface in fashion, fueled time and again by the sway of pop culture. From Madonna wearing the iconic Jean Paul Gautier conical bra corset to the outfits featured in the Regency-inspired Netflix romance show Bridgerton, the media repeatedly brought corsets back into the spotlight.

Our culture’s dual attitude towards corsets, like fashion as a whole, is more than just a matter of taste. It speaks volumes about our culture’s tangled relationship with women, their fashion, and the history that shapes both.

A brief history of corsets

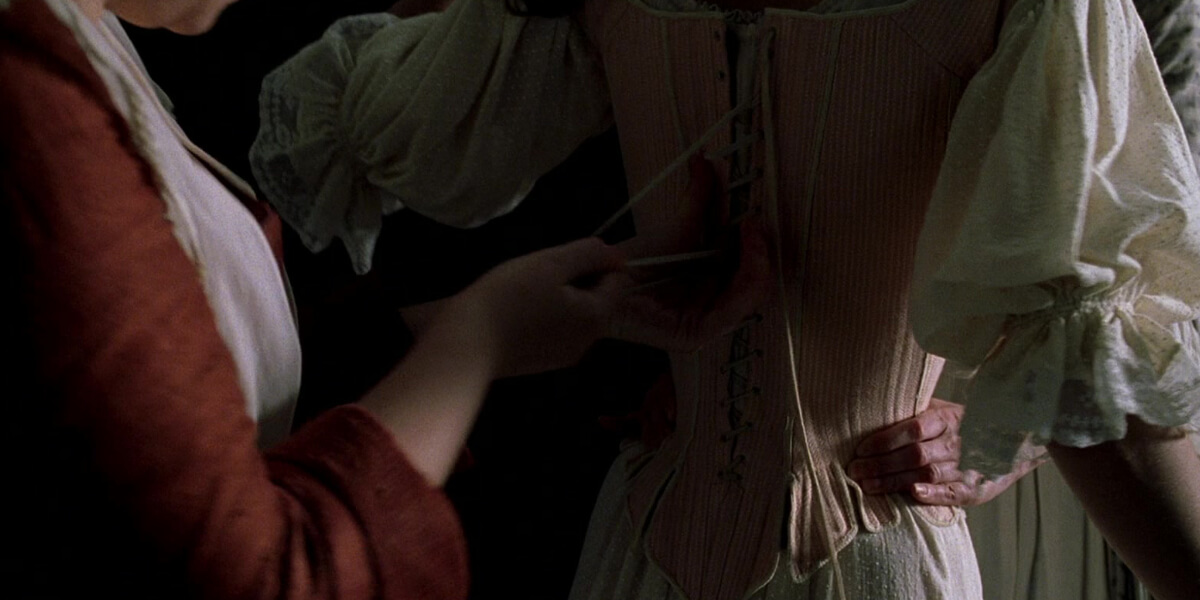

Corsets are a form of undergarment that supported the bust and allowed the wearer to achieve the fashionable body shape of their time. From the Renaissance to the Twentieth century, they were a standard part of the outfits for women and femme individuals.

References to corsets first appeared in the early sixteenth century, when bodices stiffened with rigid stays—often whalebone—emerged and eventually found a place in Queen Elizabeth I’s wardrobe. Over the centuries, their form, purpose, and materials shifted alongside fashion trends and technological innovations.

For instance, in the wake of the French Revolution, the extravagant trends of the ancien régime became démodé. This shift led to fashionable apparel becoming less constricting, gentler, and lighter. The corsets of the time had an appearance that matched this trend. One striking example comes from the V&A museum: a corset crafted from white cotton twill, partially boned, and cut to end neatly at the base of the ribs.

No era shaped our modern perception of the corset more powerfully than the Victorian age. At the beginning of this period, the fashion trend included sizable skirts, almost off-the-shoulder necklines, puffy sleeves, and a small waist. The corsets were to match: long and able to round the bust, shape the hips, and cinch the waist. With each wave of technological innovation, the corset evolved. One of the earliest shifts came with the advent of synthetic dyes, which suddenly made vibrant colors possible. Later, with Edwin Izod’s invention of steam molding, corsets became more rigid and rounded. During this time, a practice that Victorians themselves considered controversial emerged: tightlacing.

Why do we think corsets were so dangerous, but we are still obsessed with them?

In the Victorian era, the demonization of tightlacing went hand in hand with that of corsets. This attitude is evident from the 1892 pamphlet ‘Fashion’s Slaves‘ by Doctor Benjamin Orange Flower. Like many other physicians of his time, he linked corsets with a range of health issues. Headaches, tuberculosis, indigestion, heart disease, and gynecological diseases. A cocktail that inevitably led to a longstanding medical belief that corsets condemned women to an early death. However, these hypotheses, in retrospect, are an example of gender bias in medicine.

In a 2015 paper, the anthropologist Rebecca Gibson of American University analyzed the skeletal remains of women who lived between 1700 and 1900 to assess the impact of corset wearing on longevity. Her research found that while corseting caused skeletal deformation, these women lived longer than the typical lifespan for their day.

If corsets weren’t deadly, they weren’t necessarily constricting either. Working-class women who engaged in manual labour and childcare wore them as well, not just royals and aristocrats.

These misconceptions about corsets, though, have seamlessly made their way into highly popular media set in the past. From ‘Gone with the Wind’ (1939) to ‘Titanic’ (1997), period dramas have shaped the way contemporary audiences perceive corsets. Yet, in actuality, as American historian and curator Valerie Steele said in ‘The corset : a cultural history’, her landmark work on the subject, “Corsetry was not one monolithic, unchanging experience that all unfortunate women experienced before being liberated by feminism. It was a situated practice that meant different things to different people at different times”.

The reason why we are so easily convinced that women of the past lived for centuries in a state of constant danger and discomfort is that not only do we tend to see people of the past as fundamentally different from us, but also because our culture has long depicted women’s interests, particularly fashion, as trivial pursuits.

People of the past, however, were driven by many of the same feelings and needs as we are: the desire to express themselves, to find acceptance, and to live their lives as fully as possible. Fashion has long been part of how people of all genders try to fulfill these needs, a second skin of our own choosing. That’s why we keep returning to trends like corsets—fashion statements of the past—continuing a conversation with a history that, while not always fully understood, remains a vital part of our cultural heritage.